Аuthor: Mikhail Kildyashov

For all their differences in mentality the Russians and Germans have a key point of contact

The fate of Russian and German civilizations is so closely intertwined – historically, ethnically, aesthetically – that any processes taking place in the modern world for sure in one way or another impact upon the relations between these two passionate peoples.

In the past centuries we have been through a lot: fruitful cooperation, mutual enrichment, economic rivalry, and a world war, which, in essence, was not a geopolitical struggle between states but a battle between two worldviews, two scenarios for humanity.

With regard to the complex relationship between these two nations, we talked to esteemed Russian artist Gennady Zhivotov, professor at the Russian State University for the Humanities.

– Gennady Vasilevich, today in your opinion are there more points of convergence or divergence for Russians and Germans?

– It is surprising, but despite the long, difficult and contradictory relations between the two nations, in our philosophical thought and in the media the “German question” did not form, did not crystallise, in the same way as, for example, the Russian, Polish or Jewish questions. Apparently, this is linked to the fact that despite all the differences in mentality, Russians and Germans have a key point of contact. Both nations are by nature creative. Just the Germans create as rational people of the earth, and the Russians create through the spirit, they are people of the sky and the cosmos, of dream and myth.

– Yet not accidentally you talked about the contrast between the Russian and German mentalities. After all, in this sense we can refer to the classic example of Oblomov and Stolz…

– Goncharov’s Oblomov and Stolz are not opposites, but only two facets of the same phenomenon. They both seek to create. From this comes their mutual attraction, the impossibility to exist one without the other, the necessity of their being together, like Martha and Mary in the Gospel’s parable.

– That is, for some kind of universal harmony the combination of German rationality and Russian irrationality is even necessary?

– The German experience, transferred to Russian soil – the German form, inspired by the Russian essence – has proved to be very productive. Thanks to this, in the age of Peter in a quarter of a century we completed a journey which in Europe went on for three hundred years.

The words of Alexander Prokhanov were right when he said that during the Romanov empire “Germans ruled over the immense land of the Russians”. But these Germans also became the bearers of Russianness, which cannot be measured through blood cells. As for example in the case of “German” Catherine the Great, who strengthened the state in all spheres and in all senses. Or the half “German” Grand Duchess Elizaveta Feodorovna, who died in 1918 with an Orthodox prayer on her lips, and has been celebrated among Russian saints.

– As an artist, you certainly also see the meeting of the two nations in the arts?

– Yes of course. Here we can talk about visual arts, music and literature. It is no coincidence that Russians and Germans in various art forms have generated geniuses of equal magnitude: Pushkin and Goethe, Tchaikovsky and Bach, the venerable Andrei Rublev and Dürer. The Russian and German spirit were always in close contact. The Russian and German romantics were attracted to the primal, unadulterated origins of human nature. The Brothers Grimm and Afanasiev, by reworking them into literary form, preserved for mankind fairytales that had existed only in oral form, thereby preserving the whole world of folk ideas, beliefs, fears and aspirations.

– But how despite such close spiritual unity we have faced two world wars?

– Two nations-creators collided in the past and are now seeking to confront people-destroyers, people-consumers, or those ready to sell part of their stomach or eternal dream of El Dorado. Contemporary Germans – the descendants of genuine workers and aristocrats of the spirit – are trying to establish a system of values-hamburgers and banking operations. Consumers and destroyers are attempting all they can so that Kant, Schelling and Hegel will be removed from the cultural memory of the Germans, so that their books will be again burned in the fire of forgetfulness. But it comforts the soul to think that those Germans who somehow came into contact with Russian life and culture reject any type of sanctions, collision and conflict between our two nations.

– Do you believe that the instigators and provocateurs will also remain unscathed this time around?

– Those who during World War II hid on the other side of the ocean did not have to rise from the ruins of their cities. But this time, in case of a global war, America will not be able to easily avoid the consequences. The political, economic, military, anthropological technology of mass destruction it has developed and spread around the world is now turning against itself.

– Gennady Vasilevich, on the eve of the 70th anniversary of the victory, what is the main lesson of history that Russians and Germans must not forget?

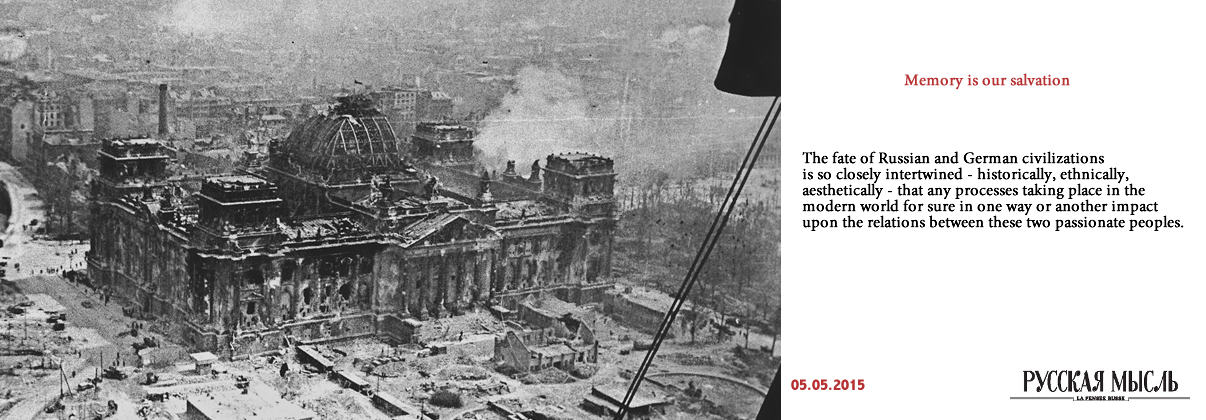

– When I think about it, two photographs appear before my eyes. In the first, a German soldier is sitting on the stairs of the destroyed Reichstag. His eyes are not lowered to the ground, like “The Thinker” by Rodin; he is looking up, like “The Thinker” by Tsaplin. The soldier looks in front of him, somewhere into the darkness and emptiness, and in his eyes the hopes and dreams of the past have faded, only despair and longing are left. And behind him in the dust and smoke ancient columns are collapsing – an echo of that antiquity which came to life in the famous “Olympia” by Leni Riefenstahl, but was not incarnated into the myth of the superman.

And in the second picture there is my father, having travelled through the warpath from Stalingrad to Berlin, with the Brandenburg Gate in the background, in May 1945. He is the soldier-winner, the soldier-hero, who dreams of going back home, to cultivate the land, to rebuild the country. I recently took photographs in that same place. There are no traces of the war in the urban landscape, but it has remained in the memory of several generations. Memory is our common salvation from new troubles. God grant that no other troops will pass through those German gates.