The Russian Festive season is a party marathon and a game of attrition

By Elizabeth Wyatt

Every country has its holidays, but Russia has always been different. There are

official and unofficial, professional and private, old and new holidays. Some come from the past, others are revived or renamed. The champion among them all is the New Year. Russians love it so much that they celebrate it twice. It officially occurs, as most would expect, on the 31st of December: the eve of January 1st. Russia’s ‘Old’ New Year is celebrated on January 14th according to the Julian, or Orthodox, calendar. And if this not enough, on the 7th of January the whole country celebrates the Russian Orthodox Christmas.

Perhaps the best part about the Russian New Year is that no one needs to go to work the next day or even the day after. This year, Russians will have 9 days of official holiday: up to the January 8th. In theory, this means there are several days to shake off the New Year hangovers. But this is only in theory. In real life it is a party marathon and a game of attrition.

So let’s have a closer look at the Russian Festive season.

Before the Communists took power, the Russian Orthodox Christmas was a very important Russian holiday: a sacred one. However, it follows that because the Communists banned religion, all religious holidays were also prohibited. Christmas became less and less popular with the passing years. So the New Year replaced it in people’s hearts.

The New Year is also celebrated with a Christmas tree, which began to be called the New Year tree, with gifts and all the other attributes. The Russian people consider the coming year to be the beginning of new life, a chance to make their dreams come true. There is a lovely tradition of making a wish whilst drinking champagne, as the clock strikes 12.00. The main attribute of the Russian New Year is a dinner table full of delicious dishes, and there is also the traditional broadcast of the President’s speech. At midnight, after his speech, the New Year party begins. It is usually a very cheerful affair, with lots of toasts and the exchanging of presents, and dressing-up.

Russians can afford to have a lot of fun on New Years’ Day. December 31st is a working day, but January 1st and 2nd are holidays, so people can stay awake all night long (which they usually do). It is a tradition to stay awake on New Years’ night, and even children try not to go to bed for as long as they can. People go out in the streets at night, they gather around huge illuminated New Year trees which are put up all around the town, and they visit friends and relatives.

After a short brake in the celebrations, Russian orthodox Christmas comes on

the 7th of January. After the fall of communist rule, this sacred Christian holiday was brought back to life and has been observed ever since. The religious nature of the holiday is preserved in Russia. Jesus is honoured on this holiday and there are numerous church services in celebration of him. People may also exchange presents, but it is not such a strong tradition. This holiday gives people another day off and a chance to think once again about Christ, God and the role of religion in their lives.

The night of the 13th to14th of January is called Old New Year in Russia. Before 1918 there was the Julian Calendar, which was 13 days ahead of the Gregorian calendar (which is used in Europe). Even though the Soviet leaders accepted the European calendar in 1918, for a long time it was necessary to specify if a certain date was ‘new’ or ‘old style’. With time, people got used to celebrating New Year according to the new calendar but the tradition to celebrate the Old New Year also remained.

As New Year is far and away the most important holiday of the year, there are a lot of customs which are associated with it. Many of these rituals are quite specific to Russia and differ from how other people around the world celebrate winter festivities.

So what do you need to know about an authentic Russian New Year?

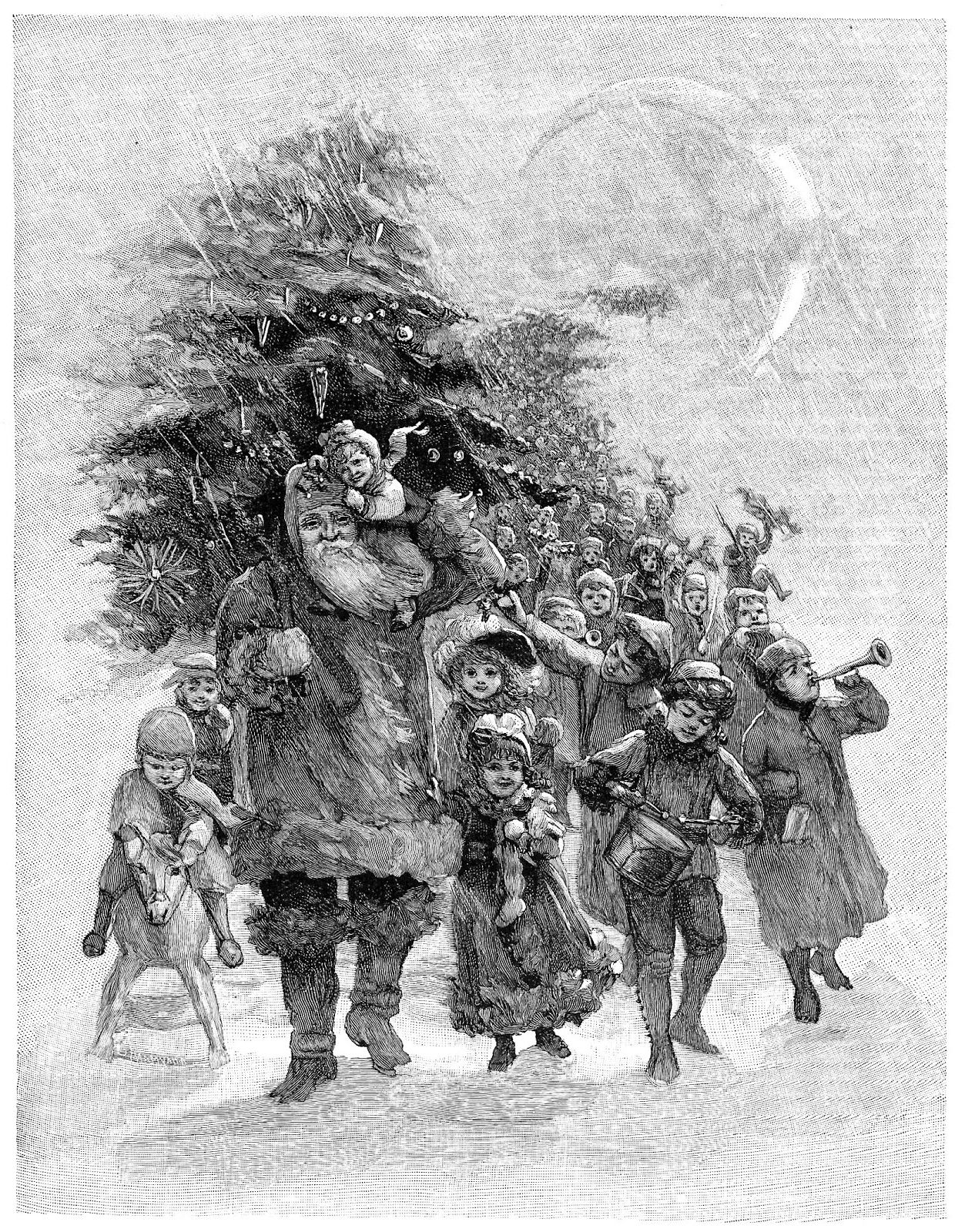

Ded Moroz and Snegurochka. The West may have Santa Claus, but he can hardly compete with Ded Moroz [Grandfather Frost] or his granddaughter, Snegurochka (the Snow Maiden). Unlike Santa Claus, Ded Moroz is not afraid to show his face and often stops by holiday parties with Snegurochka to deliver presents in person. Ded Moroz maintains his residence near the town of Veliky Ustyug (in the Vologda Region); Snegurochka is fabled to reside in Kostroma, on the Volga.

The yolka. Christmas trees were banned shortly after the revolution but, in 1935, they were reintroduced as the novogodnaya yolka [New Year’s tree] as a secular symbol. The trees tend to be small and are often made of plastic, but they are still an important festive symbol for Russians.

Celebrities, Grandfather Frost and steam. Many countries have popular traditional holiday films, but few can match the song and steam of the Soviet classic, The Irony of Fate or Have a Nice Bath (Eldar Riazanov (dir.), 1975). Zhenya is engaged and plans on spending his New Year’s Eve with his fiancée. However, as per tradition, he must first go to the sauna with his friends. They all get intoxicated, and Zhenya ends up on a plane to Leningrad. He drunkenly tells a taxi driver to take him to Third Builder’s Street, which is where he lives in Moscow. Remarkably the building looks the same and his key fits. He passes out in the apartment and is awakened by the unsuspecting Nadya. They fall in love, and, to this day, Russians still can’t get enough of this film. Television shows such as Goluboi Ogonyok [Little Blue Light], Pesnya Goda (Song of the Year; which features most top-tier celebrities) and the children’s film, Morozko (Grandfather Frost), are additional holiday staples.

Salads. New Year’s just isn’t New Year’s without the salads. We’re not talking about light green salads either, but mayonnaise-infused, and protein-thick works of art. Russians consume 2.5 kilograms of mayonnaise annually and nowhere is it celebrated more than on the holiday table. Olivier salad is usually made with mayonnaise, potatoes, carrots, pickles, green peas, eggs and chicken or bologna sausage. New Year’s literally doesn’t exist if this salad is not on your table. Selyodka pod Shuboi, or “Herring under a Fur Coat” is a layered carnival of flavours which is filled with herring, potatoes, carrots, beets, onions and mayonnaise. The beets give the salad its hints of purple.

Mandarin oranges. Supposedly this tradition began back in the reign of Nicholas II. However, due to the Soviet Union’s difficulty in growing and importing them, for decades it was discontinued. It was revived around the 1970s and remains a staple on every Russian New Year’s table.

Champagne and caviar. Nothing was more ‘proletarian’ in the worker’s paradise than champagne and caviar. While these items were in shorter supply during the Soviet period, it was then that they became part of the New Year’s tradition. The champagne is usually the Sovietskoye variety, which is available everywhere from Kamchatka to Brighton Beach. The caviar is usually red and served on buttered bread.

A midnight date with Putin. Regardless of their political affiliations, Russians around the world tune in to hear the Russian president offer his wishes for the upcoming year. Once he finishes, the clock tower on Red Square chimes, fireworks burst into the air and the New Year officially begins.

Not leaving the house until AFTER midnight to visit friends and walk around the city. For Russians, New Year’s is a family holiday and celebrations take place with close relatives on the evening of the 31st December with traditional toasts to say goodbye to the passing year. Phone calls are made to relatives that live far away. It is only after midnight that people begin the real partying. Many clubs only begin their main events at 00:30 or later.

Fireworks. As one person told me, it isn’t New Year’s if you don’t see the equivalent of a small country’s annual budget blown up in fireworks. The first New Year’s festivities that I experienced in Russia, in the industrial city of Tolyatti, involved hours of celebrating at home before going out after midnight with the whole family to see the citizenry declare war on the central square. The fireworks display was intense, loud and bright, and it is an integral part of any Russian New Year’s holiday.