On April 19, 1947, after a twenty-year break, the publication of Russian Mind was renewed in Paris in the format of a newspaper

Andrey Goultsev

The forerunner of the Parisian edition of the newspaper Russian Mind, the first issue of which was published on April 19, 1947, was the magazine Russian Mind founded in 1880 by the famous publicist and publisher Vukol Lavrov (1852–1912). The magazine was, by its self-definition, “scientific, literary and political” and quickly gained an oppositional view, becoming the mouthpiece for constitutional ideas and starting polemics with both Slavophiles and Marxists.

In police circles, Russian Mind earned a reputation as an extremely harmful press organ, and Vukol Lavrov came under covert surveillance. Like Lavrov, one of my great-grandfathers, Viktor Goltsev, who was an author of the column “Political Review” since the founding of Russian Mind and its editor, then from 1905 – its chief editor (until his death in 1906), also remained under close supervision.

Also, from the day on which the magazine was founded, Anton Chekhov collaborated closely with the magazine, all of whose works appeared in Russian Mind and only after that were published in book form.

Shortly after the revolution of 1905, a well-known politician, the right-wing constitutional democrat, historian and economist Pyotr Struve (1870–1944), who led the magazine for more than ten years, became the head of Russian Mind. In his famous project “Great Russia”, Peter Struve put forward the idea of combining Russian nationalism with liberal values. The policy orientation of the magazine opposed both autocracy and revolutionary radicalism.

The magazine was subjected to fierce attacks of Vladimir Lenin. After the Bolsheviks came to power, Peter Struve, outlining the program of Russian Mind for 1918, wrote: “In the days of the greatest humiliation of Russia, we will defend the ideals that created its power and greatness, and fight against the idols that plunge it into disaster and incredible shame.“

The magazine was subjected to fierce attacks of Vladimir Lenin. After the Bolsheviks came to power, Peter Struve, outlining the program of Russian Mind for 1918, wrote: “In the days of the greatest humiliation of Russia, we will defend the ideals that created its power and greatness, and fight against the idols that plunge it into disaster and incredible shame.“

In 1918, the Bolsheviks cancelled all “bourgeois” newspapers and magazines. Russian Mind ceased to exist after 38 years of publication. However, its story did not end there. Three years later, in 1921, Struve resumed publishing the magazine, first in Sofia, then in Prague (until 1924), and then in Paris (in 1927). He united both old and new literary resources around the magazine, where Ivan Bunin, Zinaida Gippius and Mikhail Rostovtsev set the tone. At the same time, as many of you know, Struve edited the daily newspaper Vozrozhdenie (Renaissance) and then the weekly Rossiya (Russia), which inevitably diverted his attention from the “first-born”. The publication of Russian Mind soon ceased.

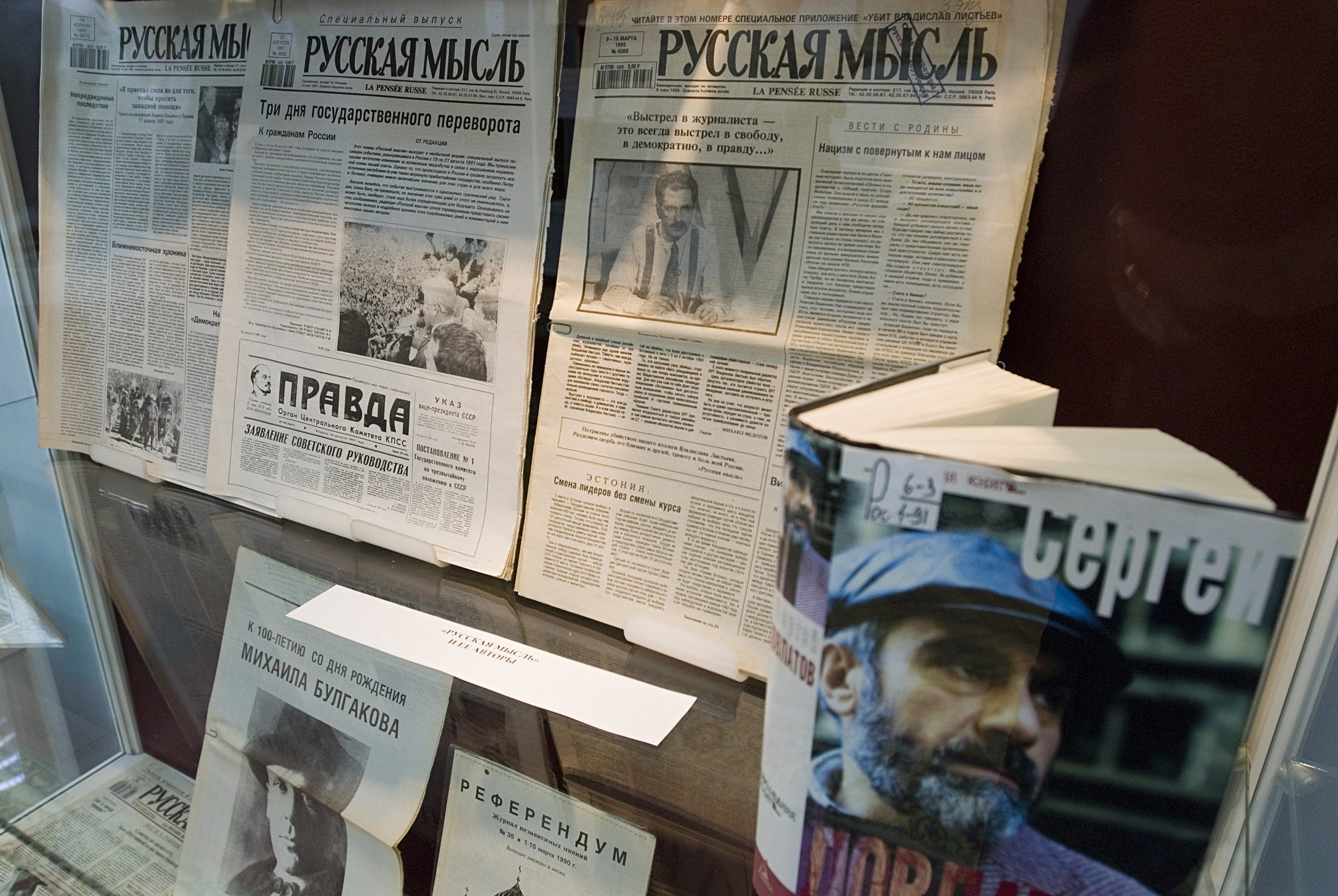

The third birth of Russian Mind – already as a weekly newspaper – dates back to 1947 and is associated with the name of Vladimir Lazarevsky (1897–1953), the first editor-in-chief (until 1953) of the revived publication. The next editor was Sergei Vodov (1953–1968), then Princess Zinaida Shakhovskaya (1968–1978) and then the legendary associate of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Irina Ilovaiskaya-Alberti.

Ivan Bunin, Ivan Shmelev, Nina Berberova, Viktor Nekrasov, Joseph Brodsky, Sergei Dovlatov, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, Andrei Sakharov and, of course, Alexander Solzhenitsyn were among the most famous authors of Russian Mind published during the period of the Iron Curtain and the beginning of perestroika.

My collaboration with Russian Mind began in the 1990s, when, after visiting Chechnya and the refugee camp in Ingushetia in a company of Yul Rybakov, a State Duma deputy (at that time), I sent my article about those trips to the newspaper.

I easily took decision on the newspaper to send the article to, but I well remember how worried I was, waiting for the editorial decision. To my great joy, the article was approved, and since then I began to write for Russian Mind more or less regularly.

From 2002 to 2008, I worked in my favorite newspaper: first as an administrative officer, and then as a general director and executive editor (it is customary in France to combine these two positions), while continuing to write one or two articles weekly. Those were some of the most interesting years of my life. Shamelessly taking advantage of my official position, I chose topics for interviews independently and in those years, as a journalist, met with the most famous and popular people from all over the world: Mikhail Gorbachev, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Vyacheslav Butusov, the Agatha Christie band, Tanya Bulanova , Pierre Cardin and many, many others.

I remember how in 2006 I, an old and faithful Pink Floyd fan, unexpectedly received a letter from the press group of the French Federation of Motor Sport (FFSA) with an invitation to come to a press conference of… Mr. Nick Mason – the legendary drummer of the legendary band. Sure, Nick Mason is known for his racing car collection, but he is a musician first and foremost. The misunderstanding was resolved quite quickly: they simply forgot to put an advertising brochure in the letter, telling that on July 14, on Bastille Day which is the main French holiday, demonstration car races dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the FFSA will be held during the day and there will be a grand concert by Roger Waters with the participation of exclusive Nick Mason in the evening – both events on the Formula 1 race track in Mani-Cours.

In addition, it was explained that the musicians would perform the full version of the “Reverse (originally – dark) side of the moon” for the first time since 1974! Nick Mason turned out to be a common, cheerful and extremely witty interlocutor. The concert was simply brilliant. And I still, sometimes looking at my photo with him, rub my eyes to make sure that I didn’t dream of our meeting. And at night, looking at the moon majestically, imperturbably floating above our heads, I quietly sing after it: “All that you see // All that you love // All you create // All you destroy // All that you say // And everyone you fight // And everything under the sun is in tune // But the sun is eclipsed by the moon // There is no dark side of the moon really // Matter of fact // It’s all dark.”

In general, I am still glad that I used my “official position” to the best I could, and I am not ashamed of this fact, since the responses from the readers were encouragingly positive, and professionals appreciated my efforts too: for four years in a row, my interviews and essays received diplomas of the competition “Golden Pen of Russia”. Obviously, those were the years when the “stars were aligned” as they should be.

It is absolutely necessary to note that not only journalistic, but also administrative work is insanely interesting in Russian Mind. Since 2004 we have developed and set up the release of the insert ParisINFO especially for our readers in France. Since the main newspaper was sent to 50 countries by that time, it was this insert that became our connection with local associations and compatriots and their mouthpiece. From regular, often stormy and “mass” (up to 20-30 people) meetings in the editorial office, the largest association at that time, the Russian Community of France, was established in 2005 almost by itself, where Russian Mind became the centre of attraction and information. We have held dozens of festivals, exhibitions, concerts and discos for mutual benefit, where Russian Mind acted as an information sponsor, and the Russian Community was an organizer.

In 2005 Russian Mind celebrated its 125th anniversary with the release of a special issue in French, which made it possible to tell the French what their Russian-speaking fellow citizens live and read about.

Russian Mind is a Russian, French and pan-European edition at the same time. It is a unique chronicle of the life of the Russian émigré community for three quarters of a century. The historical role of Russian Mind consisted in the fact that during the years of the maximum separation of the world, the freedom of the Russian word always found itself on its pages. Brilliant talents of Russia met the world here: wonderful writers, philosophers, historians, artists, publicists. They told the truth about what was happening in the Soviet Union. The publication stood on tough anti-communist positions but was never narrow-party.

In 2006 we solemnly donated our archives to the Russian State Library (RSL). In France, all printed editions are automatically stored in the central library, so that here readers can always find the necessary issue. In Russia, for obvious reasons, no one had a complete archive. This very sensitive and important event was widely covered in the media. And, as usual, we faced some challenges. Despite the mass advertising of the event and banners hung all over Moscow, the customs officers delayed the clearance of our parcels to such an extent that I took one of the annual files of Russian Mind in our branded binding with me from Paris, planning to simply put it on top of a pile of some other newspapers during the filming of the transfer of archives. But fortunately, on the last day, the customs gave the go-ahead, and we prepared the exhibition in compliance with all the rules. Indeed, in addition to newspaper filings, we handed over manuscripts and special issues of Russian Mind printed on thin, almost tissue paper (the only way they could be brought in and taken out of the USSR), books with author’s autographs, original drawings and unique photographs.

And the next year we celebrated the 60th anniversary of the Paris edition. Russian Mind gained such popularity, that the IX World Congress of Russian Press was timed to coincide with this event and was held in Paris as “our guest”. We were visited by 250 journalists from Russian-language publications from all over the world!

In general, dear readers, you understand that I was, and remain, one of the most faithful admirers of Russian Mind.