Pages of life journey of an outstanding journalist (continued from No. 143/03/2022)

MIKHAIL LEPEKHIN

In the last decade of the 20th century Victor Nikolaevich Loupan was known as a remarkable journalist, but in the first two decades of the 21st century he enjoyed a reputation as an experienced publisher and a prominent publicist. Such evolution was natural and instructive.

The interview given long ago to Loupan by Patriarch Alexy II led to an unexpected consequence. One day, when returning from Russia in a half-empty first-class cabin, Victor was found side by side with a respectable man of his own height; a conversation ensued. His companion turned out to be Count Sergei Sergeevich Pahlen, who had previously read Loupan’s articles in Le Figaro Magazine. Both of them were fascinated by the theme of “royal remnants”, and turned out to be like-minded people on a number of other issues related to Russia. Count Pahlen, then chairman of the Fiat concern, founded the publishing house Éditions des Syrtes intended to publish books corresponding to the idea of traditional European values.

Since the 18th century the life of the noble Baltic family of Pahlen has been inextricably linked with Russia, and Sergei Sergeevich’s interest in the past and the present of a great power was natural. What was happening in Russia did not cease to excite him, but unlike most people in Europe and Russia, he was not filled with pessimism, but sincerely believed that Russia was destined for a rapid rise and prosperity, and even in the very near future. Given the status in which Russia remained in the late 1990s, such a point surprised by its rare originality of worldview, because it hardly occurred to anyone to make such optimistic forecasts at that time. Moreover, being personally acquainted with Putin, Count Pahlen connected the coming revival of Russia with his – then little known– name.

Since the 18th century the life of the noble Baltic family of Pahlen has been inextricably linked with Russia, and Sergei Sergeevich’s interest in the past and the present of a great power was natural. What was happening in Russia did not cease to excite him, but unlike most people in Europe and Russia, he was not filled with pessimism, but sincerely believed that Russia was destined for a rapid rise and prosperity, and even in the very near future. Given the status in which Russia remained in the late 1990s, such a point surprised by its rare originality of worldview, because it hardly occurred to anyone to make such optimistic forecasts at that time. Moreover, being personally acquainted with Putin, Count Pahlen connected the coming revival of Russia with his – then little known– name.

When Yeltsin announced his resignation and appointed Prime Minister Putin to be acting President of the Russian Federation on December 31, 1999, the forecast of Count Pahlen began to come true. In January, Sergei Sergeevich called Loupan and suggested that he immediately begin writing an essay on a given topic, namely, the beginning of a new rise of Russia. On March 26, 2000, Putin was elected President of the Russian Federation, then on May 7 he was inaugurated, and in June Loupan’s book Le défi russe (The Russian Challenge) was published, instantly attracting the attention of the world media.

The title of Loupan’s book refers to one of the pillars of French ideology in the last third of the 20th century, J.-J. Servan-Schreiber’s bestseller The American Challenge (1967). For Europe in the 1960s, the publication of this work was comparable in its consequences only to O. Spengler’s The Decline of the West (1918) published half a century earlier. Imbued with fear of US investment expansion into Western Europe and the impending death of European culture, economy and industry from the consequences of Americanisation, Servan-Schreiber’s bestseller, along with the works of G. Kozhev, served as the ideological basis on which the building of the European Community was being erected since the beginning of the 1970s. Loupan’s book borrowed only the title from The American Challenge, but its national optimism clearly goes back to Servan-Schreiber’s next book, The Awakening of France (1968) – alas, being completely shadowed by the author’s name due to the unfortunate events of that year.

In the historical and literary constructions of the author of this article, the matter of the secondary nature or dependence of the text has always been perceived as a derivative of the personality of the author. So, M. V. Golovinsky was perceived by me as an imitator of F. M. Dostoevsky and E. Drumont, like Hitler of Napoleon and Ataturk or Stalin of Nicholas I and Alexander III. Loupan was no exception: in a conversation with me, Victor did not deny dependence on Servan-Schreiber’s two books and on the charm of his personality as a master of outrageousness, a great analyst, and a cult person in world journalism. Here I also note that the book The World Challenge (1980) by Servan-Schreiber and the book The Japanese Challenge (1970) by H. Hotberg who imitated him, were not known to Loupan – for their total practical uselessness.

By imposing the pattern of The Awakening of France on the fabric of the narrative about Russia at the end of the 20th century, Loupan achieved the desired effect. Servan-Schreiber contrasted the receding greatness of de Gaulle’s France with renewed France, which was supposed to make a breakthrough into the future and become the head of the coming united Europe – this was one of the goals of the Radical Party, where the author of the book was one of the leaders. In the year of its publication, the hot Parisian summer crushed the political careers of both de Gaulle and Servan-Schreiber. The main story line of The Russian Challenge is also built on the emphasised opposition of the bygone era of Yeltsin to the coming brave new world under the leadership of Putin.

In conclusion, note that in Russia, Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber (1924–2006) is still an unknown figure shadowed by his famous son David (1961–2011), a promoter of a healthy lifestyle. As for de Gaulle, for Loupan he has always been the greatest political figure of France in the 20th century, who built the system of values that the French (for the most part) are guided by to this day. I had a chance to talk with Victor about the personality of the founder of the Fifth Republic. Despite his sympathy for General Giraud, it was de Gaulle who was more sympathetic to Loupan, because he succeeded, but the other one lost. More than once Lebed pointed to de Gaulle as a role model: for him, he served as a perfect combination of a military man and a politician, who was independent in making even the most unpopular decisions and taking full responsibility. Loupan has repeatedly compared the beginning of Putin’s rule with de Gaulle in 1958, perceiving their ascent to the pinnacle of power as the dawn of a new era. Loupan’s extraordinary reverence for the memory of de Gaulle was influenced by the traditional sympathies for the ardent anti-Americanist, which was common throughout Russia and France, as well as Victor’s long-term acquaintance with Prince K. Ya. Andronnikov (1916-1996) who was de Gaulle’s personal translator.

The main idea of the book was that the Putin phenomenon was the beginning of a new era in the history of Russia. The author was forced to explain the main stages of Russian history since the late 1980s, to the Western reader. The description of the Yeltsin’s decade was sustained in emphatically gloomy tones with a detailed and objective analysis of the failure of Yeltsin’s foreign and domestic policy. Moreover, Loupan did not allow himself even the slightest irony in describing Yeltsin’s personality. Created according to the canons of political biography, the “portrait of Putin against the backdrop of an era” was built on the contrast of personal qualities and public service of the former and new rulers of Russia. Putin appears as the restorer of the country’s former greatness, its imperial traditions of the past – meaning imperial Russia and the USSR. The historical continuity of Russian statehood with the arrival of Putin begins to recover despite the opposition of the West – such conclusion was made by Loupan.

One of the most significant fragments of the book is devoted to the perception of the “Russian idea” by the West. According to the author, and from the point of view of the West, Russia should not exist at all. The Cold War did not end with the abolition of the USSR: the lowering of the red flag over the Kremlin on December 25, 1991, only marked the transition of the struggle to a new level. Anti-communism and anti-Sovietism gradually evolved into Russophobia. (“They were targeting communism, but reached Russia”, – this is how A. A. Zinoviev evaluated the actions of the intellectual opposition even before Loupan’s book). According to the author, in the future, the confrontation will only grow, because the world does not need strong Russia at all. The modern developments have confirmed this thesis.

One of the most significant fragments of the book is devoted to the perception of the “Russian idea” by the West. According to the author, and from the point of view of the West, Russia should not exist at all. The Cold War did not end with the abolition of the USSR: the lowering of the red flag over the Kremlin on December 25, 1991, only marked the transition of the struggle to a new level. Anti-communism and anti-Sovietism gradually evolved into Russophobia. (“They were targeting communism, but reached Russia”, – this is how A. A. Zinoviev evaluated the actions of the intellectual opposition even before Loupan’s book). According to the author, in the future, the confrontation will only grow, because the world does not need strong Russia at all. The modern developments have confirmed this thesis.

The book was written for France, but it turned out to be more in demand in Russia than in the West. The reason is quite simple: in France, the name of Loupan was more attractive, but in Russia, the opinion had already been formed in the minds of readers by the leading mass media, and Victor obviously could not change it (note that the absence of an English translation of the book is typical). The success in Russia was due to the fact that the author interpreted the facts known to the Russian reader in a positive sense for the authorities, and he did it simply and intelligibly, inspiring the readers for optimism that was previously unusual for them.

Count Pahlen expressed his wish that The Russian Challenge be translated into Russian as soon as possible and then published in Russia. Being well acquainted with S. A. Kondratov, the owner of Terra, then largest publishing house in Russia, I arranged for the publication. Without any delay, the translation was completed and the original layout was made up. Note that the translator (V. M. Multatuli) and the typesetter-proofreader (S. K. Egorov) categorically opposed to mentioning their names in the book glorifying Putin. These were the realities of 2001: if in Russia and abroad the new head of state appeared as a renovator and reformer, then in Saint Petersburg they still continued to see him primarily as an accomplice (variant: associate) of the notorious A. A. Sobchak.

When signing the contract, Loupan was amazed by the act of Kondratov, who unilaterally changed the pre-negotiated terms of the contract to his own favour. Nevertheless, Victor accepted them, in turn asking him to insert one outwardly unimportant clause, with which Kondratov agreed. Having left the meeting, Victor exclaimed in amazement: “He wanted to deceive a Moldovan?!” As a result, the contract was concluded on the terms being more favourable for Loupan than it was in the original version. Nevertheless, Kondratov managed to deceive the Moldovan by printing another 5,000 copy edition: the book widely promoted in the media sold fast. Unfortunately, Terra refused to publish a book of interviews and reportages by Loupan, which I had planned to issue in the same type of design.

On March 13, 2001, the presentation of the newly published The Russian Challenge took place at the Russian Cultural Foundation. It was the joint triumph of the publisher and initiator, Count S. S. Pahlen, the author V. N. Loupan, a hospitable host N. S. Mikhalkov (that book fully corresponded to his views) and I. L. Shurygina, a deputy director of Terra who curated the Russian edition. I was amazed at the number of speakers, as well as people not included in the program, who tried to contribute their patriotic two cents. Since the belly is not filled with fair words, we switched to a perfectly organised buffet, and it was a real holiday for everyone. Victor was amazed at the number of people who came to him to get an autograph, introduce themselves, or clink glasses; he never stopped answering questions and giving interviews. The aura of total joy from a worthy event is still memorable. The book, combined with its presentation, instantly brought Loupan fame in Russia: since then he has become a media person and willingly agreed to give interviews.

Moreover, the term “very timely book” turned out to be quite applicable to “The Russian Challenge”. Being released immediately after Putin’s inauguration, it filled the information vacuum that had formed around the name of the President of the Russian Federation. Journalists and propagandists in the year 2000 had absolutely no idea of the framework of Putin’s future policy, nor of his worldview. As for the electorate, they were simply glad that the drunken old partocrat had been replaced by a sporty young Chekist who had assumed the burden of responsibility for the country.

The book also attracted attention of the main character. Victor recalled how Putin came up to him at one of the receptions and thanked him for the pleasure he got from reading the book. Let me remind you that chronologically, The Russian Challenge was de facto the first book about Putin in French and Russian, written in excellent style and without the slightest sign of servility. The assessment given to his book by the head of state was pleasing to Victor: he sincerely sympathised with Putin as a politician and a person. For Loupan, he was not only one of the most important persons in the world, but also a man who achieved this power through his own efforts. Self-made Loupan sincerely admired Putin: even the imperial grandeur of political views hardly seemed so significant in comparison with the fact that a person from the lower social strata “became reasonable and great by his own and God’s will”.

But let’s go back to France.

In the last year of the past millennium, for unknown reasons, the circulation of Le Figaro Magazine fell significantly: the leading high-intellectual conservative publication of France was becoming of little demand. A question arose among the owners of the publication about the removal of Henri-Christian Giraud from the post of editor-in-chief. In this regard, the future of Loupan in this magazine also became problematic: freedom of action and decent fees favourably distinguished him from most of the employees. For this reason, Victor accepted the invitation of Count Pahlen to become editor-in-chief of Éditions des Syrtes. In his decision, the owner was guided by Loupan’s fame as an author and his focus on Russia.

In 2000 Victor parted ways with Le Figaro Magazine and had managed Éditions des Syrtes until 2002. This was Loupan’s first administrative experience, which he greatly cherished. At the age of 46, constant traveling around the world began to tire him, and the occupation of a prestigious post under experienced guidance became the starting point for a subsequent successful administrative and publishing career. Let me remind you that Éditions des Syrtes established by Count Pahlen became a highly profitable enterprise thanks to a carefully thought-out focus: the choice of themes smoothly switched from European conservatism to Russian names and books, which before were unknown to French readers (suffice it to mention The Sun of the Dead by I. S. Shmelyov and Cursed Days by I. A. Bunin).

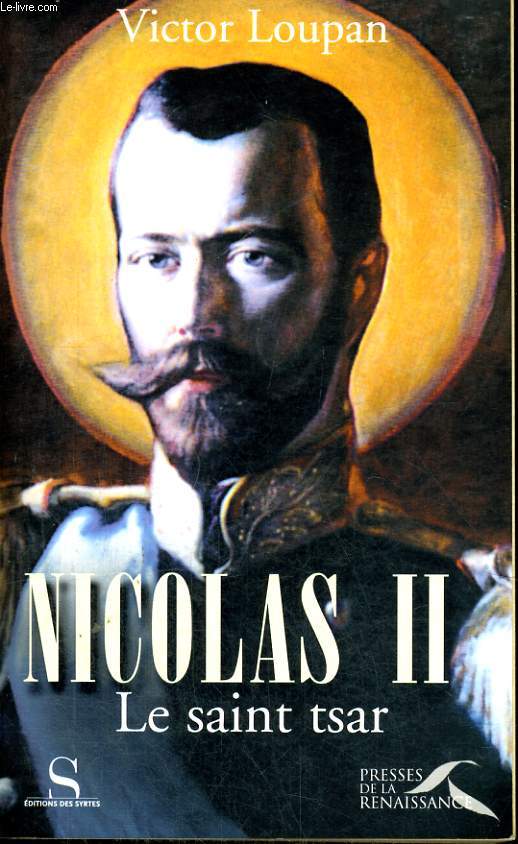

Considering the preferences of the owner of the publishing house, Loupan himself quickly created the book The Holy Tsar Nicholas II (Nicolas II, le Saint Tsar; 2001), which was an emotional retelling of the Letters from the Royal Family in Confinement (Jordanville, 1974). In France, Loupan’s book was a success, since the personality of the last sovereign, thanks to the works of M. Ferro and E. Radzinsky, was interpreted primarily from a liberal standpoint. There was no point in translating it into Russian: it was written only for French readers, and in Russia only the laziest did not write about Emperor Nicholas II in those years.

Considering the preferences of the owner of the publishing house, Loupan himself quickly created the book The Holy Tsar Nicholas II (Nicolas II, le Saint Tsar; 2001), which was an emotional retelling of the Letters from the Royal Family in Confinement (Jordanville, 1974). In France, Loupan’s book was a success, since the personality of the last sovereign, thanks to the works of M. Ferro and E. Radzinsky, was interpreted primarily from a liberal standpoint. There was no point in translating it into Russian: it was written only for French readers, and in Russia only the laziest did not write about Emperor Nicholas II in those years.

In 2002 Victor took over a larger publishing house, Presses de la Renaissance. The owner of the publishing house, the venerable Alain Noël, considered Loupan not only as a successful manager, but also a good Christian: this opinion was confirmed by the book Nicolas II, le Saint Tsar. Victor justified trust in both guises. With Noël credited as his co-author, Loupan published the impressive Investigation of the Death of Jesus (Enquête sur la mort de Jésus; 2005). The idea to bring together the news and testimonies of the death of the Savior, giving them an assessment from the 21st century scientific point of view, belonged to Noël. In his work, he attracted nine prominent Catholic and Jewish researchers from various fields of knowledge (medicine, law, archeology, textual criticism). However, according to Victor’s personal opinion, so much has been written on this topic for almost two thousand years after this event, that it would be superfluous to collect material on his own. Loupan was brought in as a director primarily to help Noël complete the book. Immersion in the world of the New Testament distracted Victor from modern squabbles. Work on the book lasted two years. Written in a living language, the Investigation revealed Loupan’s gift of a spiritual writer who managed to present a rather complex topic in a way understandable to a modern secular reader. Victor’s gift of spiritual enlightenment fully manifested itself a decade later, when he began broadcasting on Radio Notre Dame.

As for the talent of entrepreneurship, Loupan’s real triumph happened in 2005. In March, Russia was the main guest at the annual book fair; huge portraits of two Russian authors, S. A. Aleksievich (I forgot which book was translated) and S. P. Tyutyunnik (Loupan compiled the collection War and Vodka from his stories) were presented at the top of the Presses de la Renaissance booth. Victor himself walked around with a megaphone and from time to time urged the French with its help in a loud voice to take autographs and talk with living Russian classics – who by the sweat of their brow alternately inscribed books and answered questions; visitors waited in line to reach both of the classics. To my question, why he did prefer a provincial (from Rostov-on-Don) military journalist with a set of army tales, who was almost unknown in Russia, to V. V. Shurygin being not only the best military observer, but also Loupan’s longtime acquaintance with the wonderful Letters from a Dead Captain, Victor answered simply: “Too smart – the French will not understand”. For Loupan, the commercial success of the book was the main indicator of the effectiveness of his work.

Note that it was Loupan who discovered Aleksievich’s works for France, and there is also his merit in awarding her the Nobel Prize in 2015.

Service in the publishing house Presses de la Renaissance had a certain inconvenience. For Loupan, the need to work daily bell to bell at the office (a dull cramped office near the Botanical Garden was evidently incompatible with his size) was painful: “I feel like a caged animal here”. The combination of directorial duties with the position of editor-in-chief in Russian Mind (see details below) led him to realise the need to make a choice in favour of another publishing house with a more flexible work schedule.

In 2008, Loupan was invited to head the publishing house Éditions de l’Œeuvre: that year several investors (the most honourable profession in the West) simultaneously came up with a good idea to make profit of publishing books. It would be the highest madness to refuse such idealistic businessmen, and Victor enthusiastically dived into the publishing business that was familiar to him. It went on for more than five years, until in August 2013 investors ran out of funds (investments went through the publishing house Bayard). The publishing house was liquidated, but for Loupan the process of changing investors was blissful and painless: almost immediately, in 2014, he became director of the publishing house Éditions du Rocher. I can’t say anything about the products of the two publishing houses, since Victor didn’t present them to me – probably, he didn’t consider it necessary to give obviously unnecessary books. Loupan understood my tastes and preferences and invariably presented his freshly published books when we met – some of them were a source of special pride for him, he talked about the complexity of their preparation and enjoyed the result. Note that attempts to establish a joint business with Russian book publishers were not crowned with success even in the blessed 2000s, and then the idea was completely abandoned as obviously hopeless…

Loupan himself was neither a bibliophile nor a book lover: his attitude towards books was utilitarian and pragmatic to the right extent. All his children grew up reading the classics, Victor himself had to read a lot in connection with his official duties – he did not have, and could not have, a cult of the book, which was common among Russians in the 1970s, which he lost. A Western man, he never ceased to be a descendant of the Moldavian peasants, for whom the hearth is the main value. A comfortable home life is hardly compatible with book wisdom, therefore, the number of printed publications in Victor’s dwelling was reasonably sufficient, the excess was mercilessly expelled.

About the benefits of books… I remember Victor’s story about the interview with A. Pinochet. The retired dictator of Chile treated journalists with great prejudice. Having repeatedly encountered dishonesty in the interpretation of his words, in the late 1980s he refused to be interviewed, and it became a matter of prestige for Loupan to receive one. A mutual friend introduced Victor as a passionate bibliophile: this was enough to get an agreement for a meeting. The general happily began to showcase his huge library devoted to geography and military history to the guest who had flown across the ocean. Victor diligently listened to a very long story about a particular rarity, expressed his admiration, then effortlessly directed the course of the conversation in the right direction and received an agreement for an interview. Victor recalled their tour of the book kingdom with a shudder: “Mikhail, you should be in my place – you would have something to talk about with Pinochet, but I only needed an interview with him”. As a result, Loupan considered the interview with Pinochet one of his most successful experiments in this genre.

I would add a couple of words about Victor’s skill as an interviewer: he did not seek to ask many questions, especially provocative or leading ones, did not seek to involve the interlocutor in an argument or demonstrate his great knowledge. Loupan strove to give the interviewee the opportunity to express themselves as much as possible, the questions only directed the flow of the conversation. Victor always treated any interlocutor, even being personally unpleasant to him, with emphasised respect and attention.

Concluding a brief story about Loupan’s 33-year professional career, I will note (in his words) that when moving to a new position, he never lost his salary, maintained good relations with colleagues and tried not to fuel slander, avoiding to comment on the reasons and circumstances of the transition. Most of those who knew him, remember Victor as a successful businessman with impeccable manners, being friendly to his subordinates. No matter how their relationship developed further, he spoke with gratitude about the elders (Louis Povel, Henri-Christian Giraud, Count Pahlen), without whose help and faith in him Victor could not have made his career.

If Loupan is famous in the Russian Federation primarily as the author of The Russian Challenge, then among Russian emigrants he is known as the editor-in-chief of Russian Mind, which still retains the status of the leading publication of the Russian Diaspora, both printed and online. Oddly enough, during the period of global savagery and separation of mankind, small islands of printed intelligent life still survived in the middle of the Internet. The name Russian Mind, as one of the symbols of a bygone era, still connects the past with the present.

In 2006, Loupan headed the editorial board of the weekly Russian Mind, which had been published as a newspaper since 1947. The first quarter of a century that Victor spent outside the USSR coincided with the era of the highest rise of the newspaper. The publication, which until the end of 1991 received generous financial assistance from the US State Department, did not lack either eminent authors or quality materials. In comparison with its main competitor, the New York-based Novoe Russkoe Slovo (New Russian Word), Paris-based Russian Mind was superior due to the intellectual level of the printed materials and quality of editing; the amount of the fees was also its advantage. This continued until the death of I. A. Ilovaiskaya-Alberti (1924–2000). After her death, Russian Mind was saved by I. V. Krivova. In 2005, the ownership of Russian Mind passed to the Association established by several persons interested in the revival of this publication.

Its objective history deserves separate consideration. I hope that someday a thorough study of the ups and downs of a wonderful publication will be impartially written.

Immediately upon the approval of Loupan in the position, I received his invitation to become one of the permanent employees of the publication. Due to the lack of free time and the absence of habit to supply content of a given volume by a certain deadline, I had to refuse; but my refusal did not affect our good relations.

I remember how I visited Victor in their new office (near Pont-Neuf). A freshly refurbished apartment converted into an office was crammed with boxes of office equipment and paper – all the furniture was covered with foil, you could only sit on the boxes. Victor sat on the only chair fitting his size and complained about his fate. He collaborated in a weekly publication for seventeen years, but he never managed it, and only now he realised what a torment it was to manage employees, be responsible for content, communicate with authors, and control deadlines. Most of the time was taken up by the authors: in addition to the existing ones, who were surprised to learn about the miraculous resurrection of the supporter newspaper, new ones also gathered being ready to supply materials on any topic at a minimal price. For the most part, the old ones were not suitable due to their excessive intelligence: the intellectual level of readers has been rapidly falling since the beginning of this new millennium, as Loupan had already seen in Le Figaro Magazine, and he did not want to repeat the same mistake. To his surprise, Loupan found that it was easier for him to get in touch with the next generation of authors than with the previous one. The fourth and fifth waves of Russian emigrants were free from the ambitions of the third wave and were quite manageable.

In view of the fact that since September 1990 I have been on good terms with I. A. Ilovaiskaya-Alberti (and last saw her two days before her sudden death in 2000), Victor asked me some questions about several employees of Russian Mind of that era. Alas, I could not help in any way: I judged all the authors primarily by their texts, but Loupan was interested in their human qualities which he knew much better than me. About some of them (I forgot whom exactly) it was said that “they still belong to old time: now no one will read them anymore”. Victor pointed out the unacceptable predominance of serious text over illustrative material in the weekly publication: “the simpler it is written, the more people will read it” and “any picture attracts”; to consolidate reader success, brevity of the text and the absence of footnotes were required. Victor associated his vision of the new image of the newspaper (in particular, the proportion between text and image) with the global process of the progressing stupidity of mankind – and primarily in Europe. Loupan’s editorial credo was that “the newspaper is published not for authors, but for readers”.

Subsequently, Loupan succeeded in transforming the hitherto weekly newspaper into a magazine, and a new period began in the existence of Russian Mind. Of course, the monthly magazine (the format and layout corresponded to the simplified version of Le Figaro Magazine) became much easier for him to make than the newspaper.

My remark that he de nomine became the successor of the Moscow professorial liberalism at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, amused Loupan, who was a staunch opponent of any subversive ideology: “What was under Ilovaiskaya will no longer exist”. Victor tried to win over the reader – in the end he succeeded. The former reader, due to natural chronological reasons, if not died out, then stopped reading the updated Russian Mind. Now it almost never enters Russia due to the oversaturation of the internal information market and the lack of solvent demand. Over the past quarter of a century, a new reader living in the Western world has grown up: this is a Russian-speaking, successful middle-aged person, who is interested in the whole range of major global problems described in an accessible form in their native language without obvious ideological dictate and with a minimum of advertising.

Of course, many materials in Russian Mind are devoted to Russia, but there is no extreme nationalist sense or the imposition of “universal values”. The magazine does not contain frontal pro-Putin or anti-Western propaganda, but it quite correctly explains Russia’s position on the most important issues. Victor skillfully combined official and personal positions in his Editor’s Letter, as well as in the editorials that he wrote for each issue.

At the very beginning of his editorship, Orthodox Loupan was worried that the name of the newspaper was associated with Catholicism and with the neo-renovationism trend in Orthodoxy (Ilovaiskaya-Alberti was a Catholic; in 1992–2000 the newspaper was published with money from the Kirche in Not (Church in Trouble) fund. Victor asked me to propose a worthy candidate for the Orthodox column of the weekly. I immediately suggested Fr. Andrey Kuraev, to which Loupan gladly agreed. On my first visit to Moscow, I met Fr. Andrey and submitted the proposal. The venerable Protodeacon was pleased with such a flattering opinion of himself, but he had to refuse: he would not have time to write an article every week, so, he was afraid to let the editor down. When I returned to Saint Petersburg, I was overtaken by a call from Loupan. I announced the refusal – and it was a sigh of relief on his part: “It’s good that it happened: his candidacy did not pass the approval”. (I am sorry, I did not check the details.) I have no idea what prevented him from this plan, but the religious column never appeared in the newspaper. Note that Victor himself followed the works of Fr. Andrey with great interest and sympathy: their books about Dan Brown (Les démons de Dan Brown (2005); Fantasy and Truth of Da Vinci Code (2006)) were published almost simultaneously.

Later, Loupan became a religious radio columnist: since 2014 he hosted a morning broadcast three times a week on Radio Notre Dame.

More than a quarter of a century of my acquaintance with Victor did not grow into business or professional contacts. Visiting Paris at least once a year, I invariably paid him a visit. In turn, Loupan visited me three times in Saint Petersburg. We often visited Moscow, where we met under the hospitable shelter of Anatoly Petrik. Victor called me many times, usually about his publishing activities. The era of the 1990s and the 2000s was different from the modern one for the better: we were younger, there was no such concentration of anger and anxiety in the world, and the future looked great…

In 2003, I was invited to the wedding of Victor’s daughter, who married a pious Catholic descendant of an old French noble family. After the wedding, everyone was invited to an all-night meal at the mansion rented by Loupan in Marais. With oysters and wine, all night long in the company of Rene Guerra and Véronique Schiltz, I listened to Victor’s stories about his travels and interesting meetings – he was then only 49 years old, but he had seen a lot and met many persons. It would be very good if someone collected Loupan’s reports of the years being crucial for mankind (1986–2000) and published them as a separate book.

Book publishing and diligence brought good results: in the second half of the 2000s, Victor’s well-being improved significantly, and the question on buying real estate for a comfortable summer vacation for the whole large – and still growing – family, arose. According to Loupan, earlier he could not imagine that buying a house with a plot would be so exciting, but it took an unthinkable amount of time. There were many offers; properties for sale were amazing in their diversity (castles, mansions, huge plots in villages), and prices in the provinces were more and more pleasant as we moved away from Paris… As a result, they acquired an estate somewhere in the foothills of the Alps (towards Grenoble): two spacious houses built in the 17th century and several hectares of land in a dying village. It was there that the ancestral memory of the serene life, lost in the spring of 1941 in the village of Chepeleutsi, was relocated. I regret that, due to being extremely busy, I did not respond to Victor’s repeated invitations to stay there in the mountains.

The last decade of our acquaintance coincided with Victor’s monstrous workload (the demand also brought devastating health consequences). There was less and less time for meetings – and after the sudden instantaneous death of Anatoly Petrik in October 2016, we never met again in Moscow. Victor still called me with specific questions, but less and less frequently. Visiting Paris annually, I invariably paid a visit to Victor, however our conversations began to take on a reminiscent character: the departed friends replaced living people in our memories, one by one… In 2018, I was in the hospitable house of Victor and Cecile in Saint-Cloud for the last time, and in the next two years we met in the city. The last time we saw each other in February 2020 at the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral: the fellows of Véronique Schiltz at the Academy of Inscriptions and Fine Literature (Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres) ordered a memorial service for her. Two years later, in the church that became Victor’s home, a funeral service was held for him as well…

We can talk about Loupan for quite a long time: I hope that memoirs about him, as well as his interviews and reportages collected together, will be published. Arranged in chronological order, they will perfectly describe this wonderful person.

Family, circle of friends, fellows, good acquaintances and neighbours – Victor knew and welcomed everyone. He greatly appreciated the well-established life, he loved to eat, drink and talk. To the best of his ability, he tried to give back to society, and he did not demonstrate that. He was always tactful and respectful to the opinion of the interlocutor, even if it did not coincide with his own point of view. All the money earned went to his family, all free time (if any) was shared with the family. Unhurried in all his actions, the descendant of the Moldavian farmers, Loupan was thorough in everything.

Remembering Victor, you visibly realise that the family was the main value of life for him: parents, wife, children, grandchildren, brother and sister, nephews. In turn, Cecile and his family saw Victor as a mighty and unshakable pillar and affirmation of the truth on which their peaceful existence was established. Considering that Moldovans perceive themselves as descendants of Roman legionnaires, Victor corresponded to the status of the father of the family (pater familiae), but not the progeny producing sire (proletarius).

Victor organically absorbed and invested the best of what he acquired in Moldova, Ukraine, Russia, Belgium, France, and the USA, in his children. (NB! He perceived Belgium as a country incomparably more reasonable than France, in which he was annoyed by the dominance of leftist ideology and intolerance for other people’s opinions). Diligence, goodwill, joyful perception of the surrounding world and even an optimistic vision of the future have always been the hallmarks of Victor. He managed to live 67 years in own spiritual harmony. A life full of external events did not affect his inner peace of mind. “The world caught me in its nets, but failed to catch me” – as G. S. Skovoroda, one of Victor’s favourite authors, made a will to engrave on his gravestone.

On January 22, 2022, Victor Loupan passed away. It is hard to realise that a great worker, a wonderful intellectual, a cheerful and a very kind person have left us.