Oksana Karnovich

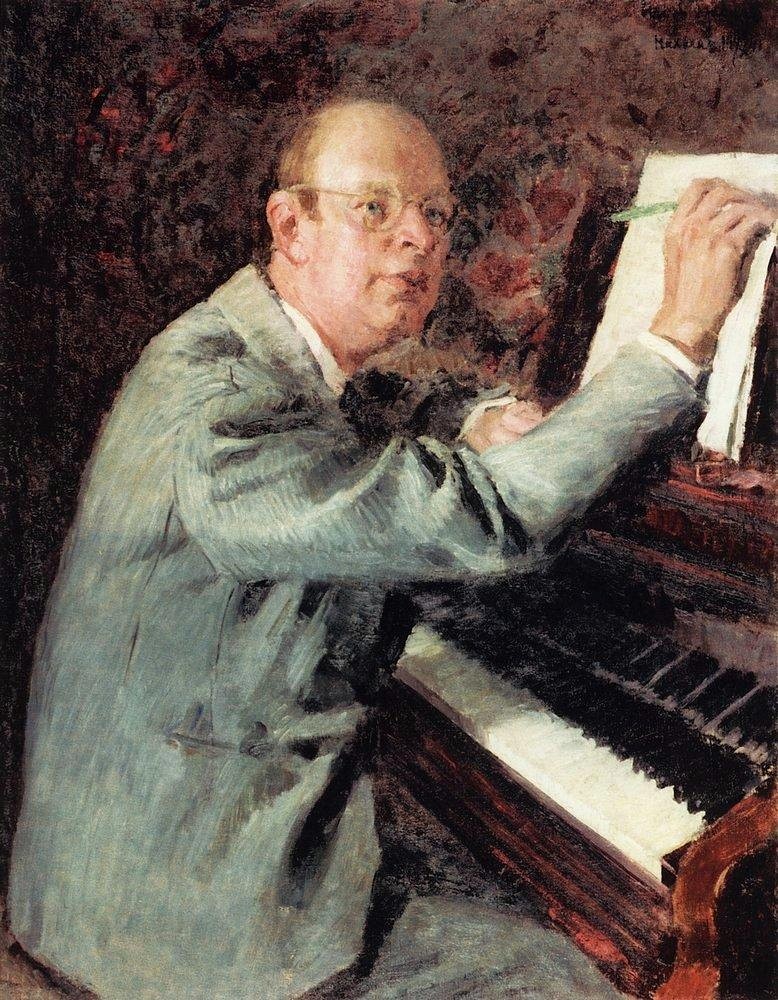

In celebration of the 125th anniversary of the composer’s birth, 2016 has been named ‘Prokofiev Year’

These days it is impossible to imagine the world’s culture without Prokofiev’s legacy: seven symphonies, eleven operas, eight concertos for solo instrument and orchestra, chamber and instrumental music, oratorios and cantatas, music for film and theatre, and seven ballets.

For over 70 years Prokofiev’s Cinderella [Zolushka], which is based on the tale by Charles Perrault, has been presented on the stages of the major music theaters of the world. Our story is focused on this work of the composer, and on its first choreographic realization.

The music written by Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev had an unprecedented influence on the choreographic incarnation of Cinderella on the stage: to interpret the tale choreographically is already not easy, but especially when it is Prokofiev’s balletic score. Prokofiev’s music does not limit the ballet’s creators: either in their interpretation of the content of the tale, or in pursuit of choreographic or theatrical forms. The sequence of interpretations of Prokofiev’s ballet is a story of various searches (not unlike the pursuit of the Prince to fit the glass slipper).

In 1936, after 20 years in exile, together with his wife Lina Kodina-Prokofieva and their two children, Prokofiev returned to the USSR. The seemingly cloudless period of creation, musical performances, meetings with old and new friends turned out to be not so bright. Commencing with a purge of various strata of the intelligentsia, there was: the broadside of Shostakovich’s article, ‘Muddle Instead of Music’ (1936), the establishment of the All-Soviet Committee for the Arts (which, led by Platon Kerzhentsev and controlled by Stalin personally, was against Formalism), the ideological scandal in Tairov’s Chamber Theater (1936), the execution of Meyerhold (1940), and the unwritten music, the lies, the injustice, the desperation: all of which completely affected the composer’s state of mind.

The first performance of Prokofiev’s opera, Semyon Kotko, which was directed by Meyerhold, was cancelled. In Tairov’s staging of Eugene Onegin (December 1936), Prokofiev intended to create the scenes missing in Tchaikovsky’s music (Tatiana’s visit to Onegin’s house, Tatiana’s dream, promenades of Onegin) but this production was banned. The score was confiscated by the Committee for the Arts and might now be permanently lost. But the actors saved the sheet music which was used during rehearsals, and gave it to the opera orchestration specialist, Pavel Lamm. He restored the musical score based on the author’s notes, and these pieces appeared in Cinderella as well as in the operas: War and Peace and Duenna.

Notwithstanding all the twists of life, when at work Prokofiev was able to distance himself, and leave everything beyond the doorstep of his creative temple. In this there is a critical difference between the two contemporaries, Shostakovich and Prokofiev. ‘All the horror everywhere, which was observed by Shostakovich, was immediately interpreted through his music, which has the same tragic darkness and powerful effect.’ Prokoviev’s grandson, Sergei Olegovich Prokofiev, thinks that Prokofiev had a completely different nature. For the composer, his creative space was ‘a kind of cathedral, and once having entered this place of worship and having begun to work, everything concerning day-to-day life (success, fame, politics) which disturbed, afflicted or even tortured the composer, was left at the door.’

‘The tragedy of Prokofiev is partially rooted in his unique inner qualities’, wrote Valentina Chemberji, an author and friend of the Prokofiev family. ‘He was a musical genius: the wisest and most talented person, and yet he remained trustful, a rounded person, untainted by, to put it nicely, ‘the specificities’ of the society in which he found himself. He innocently believed in the power of art, upon which no one should dare encroach. He was not concerned with the second, third or even the thirty-third plans of others.’

It is possible that, during such difficult years, the idea of reverting back to a benevolent old tale is not an accident. In this it is possible to decode the postulates of his own belief. For Prokofiev, faith is music. ‘But my creativity is outside of time and space’, Prokofiev wrote in his diary during his stay in New York in 1918. Similarly to Evegnii Schwarz and Nadezhda Kosheverova (one of the directors and scenarists of the film Cinderella (1947) with music by Antonio Spadevekkia ed. note), Prokofiev, with his acute mind and sarcasm, allegorically expressed in music thoughts which could not be expressed allowed.

Musicological studies paid a lot of attention to Prokofiev’s creative works: looking in detail at his melodic and orchestral composition. However, it is even more important for us to consider a sense of theatre in Prokofiev’s Cinderella, and the presentation of the artistic acoustic space which is created by him.

The formula for this space can be seen in the introduction, the main theme of which arises from layers of varied phrases which call to one another. In other words, Prokofiev juxtaposes different interpenetrating musical spaces. However, in contrast to Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty, these musical spaces are not antagonistic.

Prokofiev creates a romantic opposition by counterpoising a real human realm which is depicted grotesquely, and a world of high lyrical feeling which is not accessible to everyone. In terms of intonation and melody, this higher world is unusually rich and varied: its themes pervade and influence the music which represents the real world. It contains elements which speak to all artistic movements from the baroque to surrealism.

According to the logic of composition, and also the distribution of expressive means, Prokofiev’s main musical idea in Cinderella, which grows out of the layered musical phrase, is the confrontation between darkness and light, chaos and clear forms: the confrontation between impenetrability and themes played lovingly. There are the dramaturgically and ideationally important dramatic themes such as the clock chimes (close to the initial theme of the introduction), as well as the murmur and whisper from which the theme of the poor Fairy-godmother evolves. There is the theme which is resolved in a romantic key (the waltz at the end of Act I), and the theme which is in the spirit of a Hollywood film score (in the finale). Their styles interlace with each other within the total pattern of the work’s classical whole.

Many ballet masters handled this imaginary space of Prokofiev in various ways: giving different emphasis to the themes of Cinderella by means of choreography, scenography, art direction, and also in relation to theater in general (including ballet dramaturgy). Sometimes they used proved methods or they reworked anew this famous subject.

The story of how the composer came to Charles Perrault’s tale is very interesting. In 1938 the ballet historian and librettist, Iurii Slonimsky, envisioned the creation of a scenario for a new ballet, The Snow Maiden [Snegurochka] (after the play of the same name by Aleksandr Ostrovsky). It was intended for Galina Sergeyevna Ulanova, and was to be set to Tchaikovsky’s music which would consist of elements from several of the composer’s works. However, the principal conductor of the Kirov Theater of Opera and Ballet in Leningrad, Ariy Mosiseyevich Pazovsky, disliked the prospect of an aural collage made from Tchaikovsky’s music. Then Ulanova suggested to Slonimsky that he contact Sergei Prokofiev.

The idea to use the Cinderella story for a new ballet came to the theater critic Nikolai Volkov in 1940. The critic thought that ‘Russian ballet should not forget Cinderella because, in working on this subject, we are able to connect with the traditions of Russian classical choreography, which were identified and established in the great Tchaikovsky’s works, such as Sleeping Beauty. In December of that year Prokofiev signed a contract with the Kirov Theater of Opera and Ballet (Mariinsky). And, as a librettist, Volkov took an active part in the creation of Cinderella.

In an article dedicated to the 200th run of Cinderella in the Bolshoi Theater (1964), Volkov praised Prokofiev’s music in the following words: ‘He showed the transformation of a bedraggled girl into a princess as the prevailing of light over darkness, and the triumph of good over evil. The whole ballet was not a hymn to goodness. As in Romeo and Juliet, the ballet was about the triumph of love, only it did not occur in the tragic sphere but in the sphere of grace. All the waltzes and adagios were penetrated with genuine passion’.

Prokofiev wrote the first two acts of Cinderella not long before the start of the War, in March and April of 1941. Initially, Leonid Lavrovsky, who had earlier choreographed Romeo and Juliet, was to be the ballet’s artistic director. But, in spite of orders issued by the theater management, he failed to start production. Then the principal male dancer of the Kirov Theater of Opera and Ballet, Vakhtang Chabukiani, was appointed.

The Great Patriotic War interrupted the composer’s work. The Kirov Ballet was evacuated to Perm (from 1940 to 1957 the city was named Molotov). In mid-June 1941, Prokofiev and Volkov planned to meet with the ballet master, Chabukiani, with whom they had already developed rhythmic designs for the first two numbers. (Prokofiev created his musical outlines based on choreographic drawings.) Only in 1943, upon finishing the first draft of the opera War and Peace, Prokofiev took up work on Cinderella again and he completed the musical score by spring, 1944.

After having been evacuated to Molotov, together with Nikolai Volkov and Konstantin Sergeyev (who was directed to work on the new ballet), Prokofiev wrote Act III of Cinderella. But, essentially, Sergeyev took on a large production without yet having this kind of experience.

As a dancer, Sergeyev wanted the role of the prince to be choreographically strong and complex. As a result, of all the male leads at that time, this character’s part became a pre-eminently danced role (as opposed to roles which require proportionally higher degree of mime, or pas de deux ed. note). Prokofiev’s musical communication of an impulsive and naughty Prince challenged the usual perception of a balletic fairytale hero, and thus rejected the appeal of all its princely forebears. According to Sergeyev’s request, his first wife, Feya Balabina, who was a principal soloist with the Kirov Ballet, was appointed as his assistant.

Rehearsals started in the autumn 1943. In 1944 the Kirov Ballet returned to Leningrad after evacuation. Feodor Vasilievich Lopukhov, who took the position of the artistic director at the Kirov Ballet, decided to open the first postwar season with the already proven Swan Lake in order for Sergeyev to have time to strengthen his ideas, and for the ballet company to prepare for the first production by the fledgling ballet master.

Soon Prokofiev’s new musical score attracted the attention of the major theater in the country, the Bolshoi Theater. Notwithstanding that the ballet was created in cooperation with Chabukiani and Sergeyev, against the will of the composer, the premiere of Cinderella took place on 21 November 1945: not in Leningrad but in Moscow, under the direction of Rostislav Zakharov (with the conductor, Iurii Faier: and scenic designer, Petr Vilyams). During discussions of the new ballet, the director of the Chamber Theater, Aleksandr Tairov, said: ‘Cinderella is among those works which become classical immediately upon their appearance’.

On the birthday of the ballet master, 8 April 1946, five months after its premiere in Moscow, Konstantin Sergeyev’s Cinderella (with the conductor, Pavel Fel′dt, and the scenic designer, Boris Erdman) had its premiere at the Kirov Theater of Opera and Ballet in Leningrad. In contrast with Zakharov’s production (which comprises only 43 numbers), Prokofiev’s full score (of 50 numbers) and the composer’s orchestration were used. For the sisters’ dance with oranges, Prokofiev reprised the music from his opera The Love for Three Oranges which was not presented in the USSR in the 1940s and 1950s.

The composer created Cinderella for Galina Ulanova who became the best performer of this role. However, at the premiere in the Bolshoi Theater it was interpreted by Olga Lepeshinskaya with Ulanova as the understudy.

The theater critic, Sergei Gorodetsky, wrote these words on Ulanova’s extraordinary understanding of Prokofiev’s music: ‘Prokofiev is the most wonderful melodist. And Ulanova perfectly conceives and embodies the melodic line of his score through her dancing: the shame felt by the meek half-girl-half-child, the humble dreaming of another life, the playing with a paper fan and her dress which she is afraid to try on, the innocent astonishment when facing the freedom and glory of nature: the disbelieving awakening of her growing feelings and the pure joy at their flowering. Ulanova interprets everything with a captivating honesty, finding endless expression in the imperceptible nuances of the music, making the melody of movements seamless. Her Cinderella is Psyche herself, or ‘Darling’ [Dushen′ka] in Russian, as we said in olden days’ (This is a reference to Pushkin’s ‘Lady Peasant’, from Tales of Belkin. This story draws on themes of cupid and psyche, and in it, as is the case with Cinderella, the main protagonist changes clothes and identity in order to be able to meet the man of her desires. Futhermore, in the epigraph to ‘Lady Peasant’ , Pushkin links his story to Bogdanovich’s ‘Dushen′ka’ who ‘looks good in anything she wears’. ed. note).

Rostislav Zakharov’s Cinderella figured in the history of the Bolshoi Theater as one of the most famous and grandiose productions of the Soviet époque. The design of this fascinating and magnificent spectacle, with its abundance of fairy tale stage effects, had something in common with ballets performed in the XIXth century.

By extending the principles of symphonism into ballet music, Prokofiev was one of the first Soviet composers who developed the traditions which were established by Tchaikovsky. As Leonid Lavrovsky wrote: ‘he introduced real human emotions and complex musical forms to the ballet stage. The bravery of his musical resolutions, the clear characterizations, the versatile and complicated rhythms, and fine harmonies: all this is present in Prokofiev’s ballet music’. In its balletic dramaturgy Cinderella is closest to that of Tchaikovsky, who many times considered creating a ballet based on this fairytale.