How does Russian animalier art exist today, how is it alive?

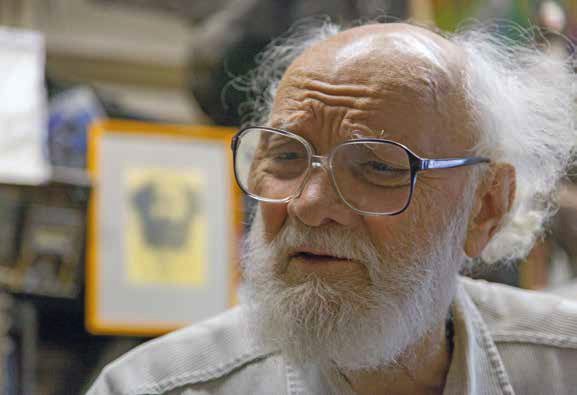

Alexey Shulgin

While the three patriarchs are alive, animalier art is also alive: it rests on them, like the Earth of the ancients – on three elephants.

Vadim Gorbatov

I met Vadim Alekseevich in November 2018 in Northern Chertanovo, visiting his workshop in the attic of a residential building. In the old days, all of us, residents of Chertanovo, literally knew each other, if not by name, then at least we could see each other in a store, at the post office or on the street. It turned out that Gorbatov’s wife, Natalya Mikhailovna, taught history at the school on Krasny Mayak Street, where I studied. We could only marvel at how small the world is. The main thing is that we were connected by our love for the Bitsa Forest, where both the artist and I walked along the same paths.

How beautiful that forest was! The area with oak trees gave way to linden trees, then a birch grove appeared, behind which a black spruce forest appeared. My heart sank when in winter I walked under the shade of not old fir trees and, having gotten used to the darkness, began to look around. Here a tit flies from one bush to another, from branch to branch; a colourful, gypsy-like jay screams obnoxiously overhead; with a barely audible rustle, a nuthatch descends head-first down the trunk; somewhere bullfinches call to each other and the croak of a raven can be heard. And you can see footprints on the snow surface. The forest lives its own life.

How glad I was to talk about all this with Vadim Alekseevich, without fear that I would be misunderstood. And Gorbatov himself was surrounded in his workshop by wonderful things, objects and little items. Long feathers of various birds hung on the walls: raptors, woodcocks, curlews. A plaster stamp of an animal footprint. Two huge elk antlers (found by the owner himself). Books, books, books. Two works of the master on the walls. One of the pictures will always live in my heart: it’s getting dark, the embers of a burnt-out fire are dying out in the snow, the forest is darkening on the horizon, the footprints of a recently departed person stretch towards the forest…

How glad I was to talk about all this with Vadim Alekseevich, without fear that I would be misunderstood. And Gorbatov himself was surrounded in his workshop by wonderful things, objects and little items. Long feathers of various birds hung on the walls: raptors, woodcocks, curlews. A plaster stamp of an animal footprint. Two huge elk antlers (found by the owner himself). Books, books, books. Two works of the master on the walls. One of the pictures will always live in my heart: it’s getting dark, the embers of a burnt-out fire are dying out in the snow, the forest is darkening on the horizon, the footprints of a recently departed person stretch towards the forest…

Gorbatov is known in the world primarily as a virtuoso draftsman of birds of prey. I was in first grade when I was given a set of postcards “The Red Book of the USSR”, which Gorbatov drew. They still sit on my shelf.

It seems to me that while the artist was making his sketches, I met him in the forest. But shyness did not allow me to come up, stand behind him and watch; it was impossible to interfere with an adult.

The future artist was born in 1940 in the village of Kachalovo, in the south of Moscow (now Nothern Butovo district). It was a real village, with the roofs thatched and where the church stretched to the sky. That church named after the Great Martyr Paraskeva Pyatnitsa still stands near the Dmitry Donskoy Boulevard metro station in Moscow. The Gorbatovs lived in their own wooden house. Parents worked at the Beekeeping Institute. His father’s name was Alexey Lukich, and the mother’s name was Faina Moiseevna.

Vadim Alekseevich told me: “I have been drawing animals since childhood. Ever since I can remember I have been drawing. And it was wartime, there wasn’t much to draw with. My brother and I fought over a stub of a pencil, my mother took it away and then gave it to us in rotation. The pencil was a chemical one, because they wrote the number on the palm when we stood in line for flour. There were no coloured pencils at all. I remember: I crushed and rubbed a piece of grass – it would be green paint. If you rub paper with a dandelion, it will turn yellow. My drawings have been preserved. I was three or four years old then.”

During the war, his father went to the front, and the family was evacuated to Michurinsk, and then to Altai. As the war ended, difficult times continued. It was hungry, but in the village everyone had their own shed, everyone had their own cattle. The Gorbatovs also had chickens, a pig, and a goat. The boy worked in the garden hilling potatoes and weeding. He also needed to cut and chop wood, feed the goat and the pig, support the goat to the herd every day and meet her in the evening.

But Vadim was drawn to the forest, and there were elk, black grouse, hazel grouse, woodcock, “everything that nests on the ground.” Vadim Alekseevich recalled that even then he went into the forest to draw. He remembered bird nests, badger and fox holes in the surrounding area.

From our conversations: “I was very passionate about Nikolsky and Komarov, but I am rather indifferent to Vatagin. Also Vadim Trofimov… (G. E. Nikolsky, A. N. Komarov, V. A. Vatagin, V. V. Trofimov are masters of the animalistic genre who worked in the 20th century. – A. Sh.). Why did I meet them? Why did I even become an artist? I had to go to the intersessional commission of animalist painters to participate in the exhibition. The commission was headed by Vadim Trofimov. I contacted him by phone. I brought my works to his home. He was a friendly person. He looked at my works with surprise. And said to bring them to the exhibition. For the second exhibition, Trofimov asked to bring sketches from life. I brought them to him. He looked and said: ‘Ugh! Amazing. Vadim, when we looked at your work with Vadim Frolov at the first exhibition, we decided that it couldn’t be real, that you were drawing from a photograph. Now it’s clear that you are a true, vibrant artist’.”

One of his well-wishers wrote very accurately about Gorbatov: “He suddenly appeared among Moscow animal painters. So much so that the dumbfounded animalistic community accepted him with great distrust: “Where was he hiding before?” But he wasn’t hiding at all. It’s just that, having been drawing animals since childhood, he didn’t see any opportunity to break into publishing houses, and apparently he didn’t really trust his talent.”

I keep all his emails carefully copied and printed on paper.

“I recently returned from Saint Petersburg,” Vadim Alekseevich wrote to me. “I visited the Hermitage. There is an exhibition of reliefs from the palace of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh. Assyria, 5th-7th centuries BC. I remember these reliefs from my student years. Lion hunting. Wonderful animalistic art. The exhibition is excellent. But it turned out that precisely those reliefs were not delivered. It’s a pity. I was hoping to see them. But still, the trip was not in vain. I wandered around the Russian Museum. And I went hunting. Three Anglo-Russian hounds. For hare and fox. The whole day in the forest, through ravines and swamps. Two young ardent male dogs tagged along with the elk and left 11 km away. We were able to catch them only by night.”

Once I asked him where it is best to look for elk antlers and when elks shed them. Vadim Alekseevich explained: “The elk sheds his antlers at the beginning of winter, but that period is extended. Antlers are more often found in dense young growth. Having lost one horn, the elk begins to butt bushes and trees in order to free himself from the second horn. He is uncomfortable, his head tilts to one side. So, if you find one horn, it makes sense to look for a second one near same place. That’s how I found both huge antlers in a young aspen wood near the swamp, which are in the workshop.”

And here’s from another letter: “In our village it’s paradise in the summer. A roe deer came to the house. We saw a fox through the window. Partridges with chicks feed themselves near the house. I didn’t go for mushrooms, but wild strawberries and raspberries are just nearby.”

Grandfather Otroshko

In December 2018, we took a night train to Yaroslavl to see Oleg Pavlovich Otroshko (he was born in 1939). The winter day is short. It’s snowing quietly, snowflakes are swirling. The trees froze without movement. The Lunka River has calmed down. Suddenly wood grouse flew over the village of Rai. Grandfather Otroshko is sitting in the log cabin – an artist, a hunter, an experienced man. He should go get some firewood and light the stove, but it’s unbearable. Winter has come to Rai. It’s time to leave.

“My gold,” Otroshko says in a singing voice, “my body was transported to Yaroslavl yesterday. I sat there (in Rai – A. Sh.) hungry. The bread had run out, it was damp and cold, and my ears were freezing on the stove.” Thank God, the grandfather survived another summer in the village.

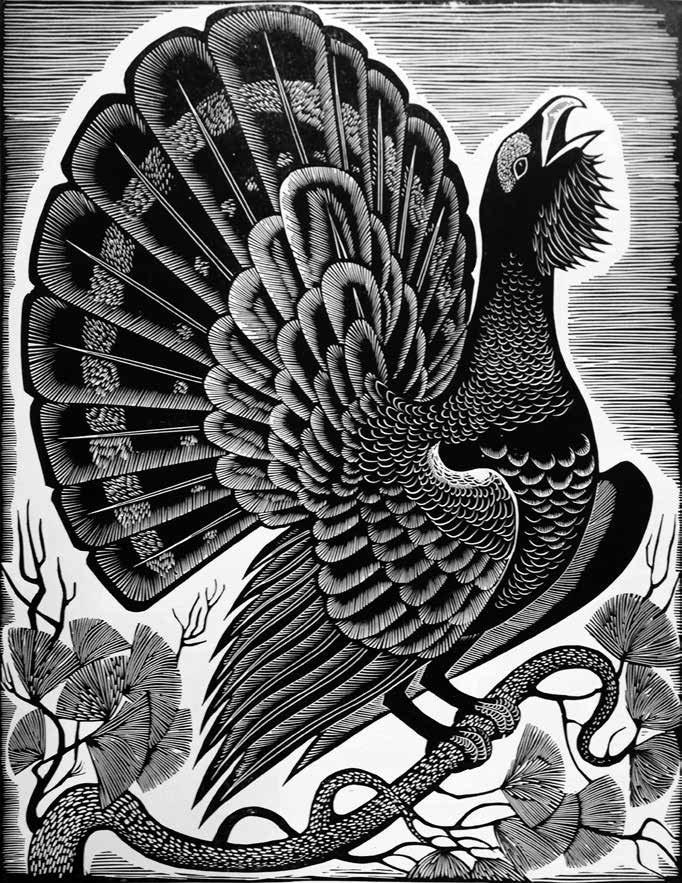

Rai is a village in the Yaroslavl region, not far from the ancient town of Danilov. In the 1990s, Otroshko bought a hut here. And Rai on Lunka became a “patrimony” and “hunting ground” for Oleg Pavlovich. How long he hunted there! And how many paintings he painted! He calls sketches from Rai ZhGDRs, which stands for: pictorial graphic and decorative works. A great worker, he made hundreds of sketches. There are thousands of sketches in the folders. All folders are themed: here are wolves, there are wood grouse…

Ayu and Boy, two dachshunds, saved him from a wild boar and distracted him for a short time, which was enough to reload the gun and discharge it at the boar. The stuffed animal, like a trophy, hangs in Otroshko’s workshop in Yaroslavl. The grandfather grins, nodding at the dead head: “Look, he’s hanging on my wall. But it could have been different.”

Otroshko lives in Yaroslavl not far from Mashinostroiteley Avenue, on the 13th floor of a brick building. Simply everything is there in his home. An old hunting horn hangs here, and on the windowsill lies a church book bound in black leather with intricate embossing. Lots of skins: wolf, boar, bear. Stuffed wild boar, wood grouse, partridge, snipe, woodcock, crow…

There were very few artists-hunters (Alexey Komarov, Fyodor Glebov, Evgeny Charushin), since animal painters were mostly peaceful observers. And Otroshko, a lover of hunting with hounds, often argued with his colleagues.

The patriarch of the genre, D. V. Gorlov, wrote in one of his letters to his young comrade: “The beast is a masterpiece of the beauty of a living being, expressing its harmony and harmonious unity with nature. Decoration of nature. An artist must not only explore, but be in love with it. This is why today murder (hunting) is a crime. Hunting is passion, not love.” Otroshko does not comment on Gorlov; he loves the patriarch and is grateful to him for his kind attitude.

– Now I want to paint a new picture. Look: I’m sitting naked in a barrel, like Diogenes, and all my hunting dogs of my entire life have gathered around me, eh?

I think the idea is excellent. On one of my visits to Yaroslavl, I saw a charcoal sketch of this painting on canvas.

“Hullo, my gold,” Otroshko barely says, rustling. “I’m buried alive. You are now talking to a corpse…”

This is the usual beginning of almost every conversation we have, but gradually he becomes inspired:

– In a year I want to hold an anniversary exhibition and make it like never before. And you will not be ashamed to say that you knew this crazy artist.

Oleg Pavlovich is a joker if I ever saw one. And an amazing artist. How to determine that an artist is outstanding? It’s very simple: remember his paintings. His Day of Reconciliation and Harmony (a mirror of modern Russian life), The Singing Wood Grouse, Dream in Rai. Pushkin and I by candlelight, Wood Grouse over Rai come into my view. This is my gold portfolio, things with which I go through life, like Pushkin, Blok, Rublev, Dovlatov…

Every year Otroshko is eager to move to his Rai. In the village he rarely gets in touch, saves his phone charging, complains about loneliness and cold. Now Rai is just one Otroshko’s house remaining from the entire village. A bear comes into his garden to eat some apples. Crucian carp population grows in the pond. Wood grouse fly without fear. Mushrooms grow abundantly behind the house. It’s a forest kingdom. And Oleg Pavlovich himself looks like the god Pan, a leshy. Barely crawling, with a staff, he walks along familiar paths, picking up mushrooms, berries, herbs. But more often he stands behind a French style easel, paints pictures, works.

He told me with bitterness that some high-ranking artists were slandering: “Ooh, he started a chicken coop!” They did not want to see Russia and the love for nature that brings a person closer to God behind Otroshko’s animals and birds.

Restrained in praise, the artist D. V. Gorlov wrote: “Oleg Otroshko has great talent and technique. It’s not easy to work sincerely, honestly, without tricks, with an open heart and love.”

And I think more and more often: it’s time to go to Yaroslavl to visit the grandfather, see him, pick up some herbs, bring him magazines, finally talk in comfort, hear: “My gold…” After all, we are loved so little in this world.

Valery Simonov

Valery Vasilyevich Simonov… I write this name and feel a wave of warmth sweeping through my heart.

In 1962, the young artist Valery Simonov overtook the initiative, undertaking to organise a second animalistic exhibition. In one of the conversations I asked him: “Valery Vasilyevich, why did you need to take on this matter? After all, an exhibition is always a bustle, pain, and you will definitely lose a lot of energy.” He replied: “Well, of course. Because I was already a mature artist, this (art – A. Sh.) is interesting to me, but I had no one to compare with how I work, what I do. Moreover, at that moment there was no one and nowhere to show easel graphic works. And most importantly, you know, everyone was still alive – Gorlov, Trofimov, Vatagin, Komarov. Everyone was alive. And why not make an exhibition?”

Valery Simonov was born in 1940 and went through all the ordeals as people who saw the war.

“My father was a military man, he worked at the airfield in Rzhev,” said Valery Vasilyevich. “When the war started, we were evacuated. Rzhev was bombed first by the Germans, then by ours. My father was involved in the evacuation of factories. He sent his family to Alatyr, then we moved to Vladimir, Sudogda, and the evacuation ended for us in Moscow. As soon as the Germans were thrown back from the Volokolamsk highway, people began to return home. In Moscow we lived in Studenchesky passage near VDNKh, on the site of the current Cosmos Hotel. But then there was remote outskirts: Rostokinsky passage, the Central Station of the Young Naturalists. Studenchesky passage was lined with two-story barracks. We lived in 8th passage. I learned the corridor-type arrangement there: the rooms where families lived were on both sides of the corridor. Then in Moscow we lived near the Kievsky railway station. The next address was a house in Krasnokazarmennaya Street. We lived in other apartments too.”

I recall the artist’s semi-basement studio in Studenetsky Lane, in the house where the poet Mayakovsky lived and died.

In days of painful doubts, I go to 1905 Goda Street to visit my friend in another world. God generously endowed Valera Simonov with talent so the young man could do anything: paint in oils, draw in gouache, watercolours, felt-tip pens, pencils, charcoal, sanguine, sauce. He created sculptures in clay, carved wood, worked with plastic, made molds and cast plaster sculptures. He was not above making magnets, whistles, and jewellery. He resembles Mozart with the ease and persuasiveness of his creations. I run to Simonov to get support, to hear his wisely ironic cooing.

Valery Vasilievich is my consultant. He always remembers and talks about all animal painters, because he knows everyone. With his help, I wrote about G. E. Nikolsky.

Simonov also writes ironic stories. “And the wolf slept heavily and anxiously. Life continued in his dream. In a dream, together with his friends, he drove and drove his victim, straining his will, strength and skill, so as not to come home empty this time. So he had to run, run, run. He loved his grey girlfriend very much. He so wants to bring his prey home, meet her at the doorway and lick her on the nose. You cannot pull a fish out of a pond without labour. Hunting is the whole meaning of his life for the sake of his beloved girlfriend and puppies…”

I wanted to write an ode to my friends, the three Kings of Beasts, whose presence in this world makes life a little kinder, better, more meaningful!