An example of fulfilling the biblical commandments

By AUGUSTINE SOKOLOVSKI, Doctor of Theology, priest

The memory of saints is celebrated daily in the Orthodox liturgical calendar. Very few are known to our contemporaries. The biography of each of them is a precious treasure of memory of those in whom the community of believers in Christ Jesus, called the Church, once saw an example of fulfilling the biblical commandments.

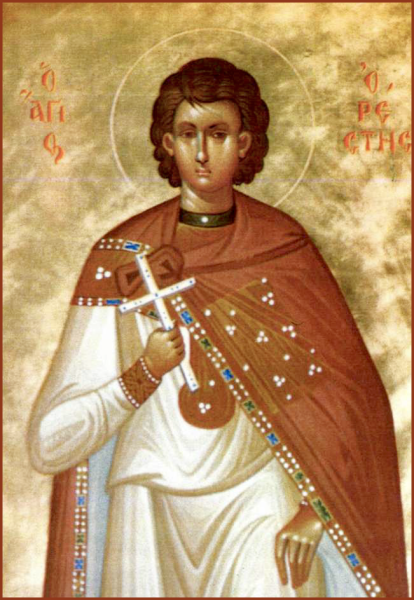

SAINT ORESTES OF CAPPADOCIA

On November 10 (23), the Church celebrates the memory of the martyr Orestes the Physician. The saint was highly revered in Christian antiquity in the Orthodox East. They resorted to his prayers asking for healing. Pilgrims flocked in large numbers to the place of the martyr’s suffering in Cappadocia. Nowadays Orestes the Physician is a forgotten saint.

Based on the place of his origin and suffering, the saint is also called Orestes of Tyana. It was a very famous ancient city in Southern Cappadocia. In the first centuries of Christianity, this place was a stronghold of paganism. The city was widely known as the place of life and work of Apollonius of Tyana (†98). This philosopher and legendary performer of miracles was contrasted by ancient pagan polemicists with Christ. Their arguments are echoed by some modern critics of religion.

Orestes practiced medicine according to his profession. The fact that the name of the medical profession subsequently became part of his name in the liturgical calendar, indicates that Orestes was a very talented doctor. “He was a God-given doctor,” as our contemporaries would say. At the same time, Orestes was an evangelist, that is, a missionary and preacher, testifying to Christ in word and deed.

During the Great Persecution of Diocletian, around 304, Orestes suffered for his faith. The reason was the accusation that Orestes’ preaching converted too many people to Christianity. At the same time, St. George, who was also from Cappadocia, was martyred for his faith in Palestine.

It is interesting that in the Georgian Church, the commemoration of the martyrdom of St. George takes place on the day when all Orthodoxy honours the memory of St. Orestes. So amazing is the communion of saints!

In the words of one of the doxologies of the Early Church, “The Blood of the Martyrs is the Seed of the Church.” At the turn of the second and third centuries, this idea was voiced by the ancient teacher of the Carthaginian Church Tertullian (†220). Orestes the Physician and St. George, undoubtedly, were that “seed of the gospel”, thanks to whose preaching and martyrdom, previously pagan Cappadocia – and many other lands – became Christian.

As a token of gratitude to the early Church, this great country gave the world many Fathers of the Church, ascetics, and evangelists, among whom were the Great Cappadocians Basil of Caesarea (330–379), Gregory of Nazianzus (329–390), Gregory of Nyssa (335–394), and even St. Nino (†335), who was the Apostle of Georgia. Nowadays, when Cappadocia has become a tourist attraction, it is important not to forget about this very important page of its Christian past.

The example of Saint Orestes clearly shows the succession of saints. So, several decades later, when Christianity spread widely within Cappadocia, Emperor Valens, who was a staunch supporter of the Arianism heresy, demanded concessions in the Orthodox faith from St. Basil of Caesarea. According to the life of the saint, he threatened Basil with death, but this did not help. Basil, as befits a Christian bishop, was not afraid of anyone or anything. “The emperor did not dare to carry out his threats and left,” says the biography of Basil.

However, not getting what he wanted, Valens insidiously divided Cappadocia into two parts. Thus, Tyana became the capital of Second Cappadocia, and the diocese of Basil was separated. The head of the now independent Tyana diocese was the heretical bishop Anthimus.

The shrine of the martyr Orestes fell into the hands of heretics. Saint Basil greatly regretted this in his works. Like all Orthodox Cappadocians, the saint perceived Orestes the Physician as his true father in the faith. After all, Orestes preached and became a martyr for Christ in Cappadocia.

It is known that the only complete collection of the lives of the saints in Russian belongs to St. Demetrius of Rostov (1651–1709). The saint devoted more than two decades to writing this immortal work. One day, in a vision, Saint Orestes appeared to Demetrius to tell him how to write correctly about the saint in his life.

SAINT GREGORY OF NEOCAESARIA

Let us move from ancient Christian Cappadocia to the lands of the ancient Pontic Kingdom. On the last day of autumn, the Churches following the Julian calendar honour the memory of St. Gregory the Wonderworker (213–270). The saint was the bishop of Neocaesarea. Nowadays it is a small city of Niksar in the central part of the Black Sea region of the Asia Minor. In ancient times, Neocaesarea was a significant city, an important political and religious centre of those lands.

Saint Gregory was a hero of the faith, a role model for the great Fathers of the Church. Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and Gregory of Nyssa, and others, considered Gregory as their spiritual father. Without them, the formation of the great Orthodox tradition of life and thought in the form, in which it has reached us, would have been unthinkable. Among the saints, Gregory was truly great.

The ancient Church did not look for miracles, however, Gregory, for the power of the signs he performed through the gift of grace, was called a miracle worker.

This is a rare addition to a name, even for saints. The grace to perform miracles, given to people in the Church, is mentioned by the Apostle Paul: “And God has placed in the church first of all apostles, second prophets, third teachers, then miracles, then gifts of healing, of helping” (1 Cor. 12:28). Due to the mysterious spiritual succession, Saint Niсholas of Myra was subsequently called the “Wonderworker” as well.

In addition to working miracles, Gregory became famous as a shepherd, missionary, evangelist, theologian, and philosopher, and even compiler of canons. They became part of the Orthodox Book of Rules. Their significance in the structure of the Orthodox Church is immutable to this day.

The father of Gregory the Theologian, Bishop of Nazianzus Gregory the Elder (276–374), was named in honour of the holy bishop. In the Orthodox liturgical calendar, he is also venerated as a saint. The brother of Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, dedicated to him a Sermon.

This interesting text preserves a lot of information about the life of the saint. St. Gregory the Wonderworker was born in 213 in Neocaesarea, into a pagan family, and was named Theodore, that is, “gift of the gods.” At the age of 14 he was orphaned. The saint’s teacher in faith was the famous Origen (185–253). He was baptised consciously when he was about twenty years old. The very name “Gregory” means “awake”, “vigilant”, “waiting for the Second Coming of Christ”. Like the name “Anastasia”, which means “resurrection”, Gregory is a typically Christian name. It is a “dogma name,” because it expresses one of the beliefs by which Christians of the first centuries lived.

He wandered a lot in search of wisdom and faith, then returned to his hometown, where he served as bishop from 238 until his righteous death around 270. When Gregory came to Neocaesarea, the city was completely pagan: there were only 17 Christians in it when he came. And there remained only 17 idolaters when he departed to the Lord. It turns out that Gregory’s greatest miracle was the preaching of the Gospel, the conversion to the life-giving Faith of Christ of a huge number of people by example and word.

Gregory was a confessor of the faith. He survived the severe persecution of Decius (249–251), when many Christians fell away from the faith. Gregory endured torture, did not renounce his faith, and remained alive. The early Church knew almost exclusively the holiness of martyrs. After all, almost all the Apostles were martyrs. It is important that it was Gregory of Neocaesarea who became the first saint bishop in history who was not a martyr. Moreover, it was his contemporaries to venerate him as the saint.

Obviously, the name “Wonderworker” in relation to Gregory in the mouths of his contemporaries was not just praise. For the Fathers of the Church, it became a confession. For it testified that two centuries after the Ascension of the Lord Jesus, God visited His People again (cf. Luke 7:16). The God of the Bible is the source of signs and wonders. God is the one who takes you by surprise.

SAINT AMPHILOCHIUS OF ICONIUM

After Cappadocia and the Pontic Kingdom, let us remember Lycaonia. This ancient region in the central Asia Minor, with its capital at Iconium, modern Turkish Konya, was enlightened by Christian preaching in apostolic times. Among the considerable number of the ancient saints of Lycaonia, the Church especially honours the memory of St. Amphilochius of Iconium (340–394). The saint was a righteous bishop and a great theologian, a hero of the faith in opposing the Arianism heresy.

Let us recall that Arianism is the name given to the doctrine asserting that the Son of God incarnated in Christ Jesus was created by God. The Church, based on the Bible, believed that the Son of God was uncreated, was divine, and equal to God. He has always been there. There is no “gap” between His existence and the existence of God Himself. Because, as Jesus Himself says in Scripture: “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30). The Creed calls the Son of God “consubstantial” with the Father.

This understanding was given to the disciples of Christ, the Apostles and the Church Itself, on the Day of Pentecost, by the Holy Spirit. It was based on the vision and reading of the words and deeds of Christ in the light of the accomplished Paschal Mystery, the Resurrection of Jesus, and His Second Coming, which, as Scripture and the Creed testify, will soon inevitably occur (Rev. 22:20).

The Arians relied on those passages of Scripture where Christ, before His Resurrection, testified to the primacy of God and the Father. In theological language, this is called the pre-Easter reading of the Bible.

Arius was not the first to think this way, but he was the first to express this opinion loudly and unequivocally. It is important that in the understanding of the Ancient Church, this was precisely what made a person a heretic. “It is not heresy that makes one a heretic, but persistence in error,” wrote the great 17th-century theologian, Bishop Cornelius Jansenius (1585–1638).

It is noteworthy, that the heretics themselves did not consider themselves Arians. Many of them shared the beliefs of Arius, but they were ready to renounce him. He was an Alexandrian priest, that is, formally he could not lead a significant church party. While considering themselves as completely Orthodox, the heretics were divided into many factions.

Nevertheless, in the second half of the 4th century, Arians made up the overwhelming majority in the episcopate of the Universal Church in the East. It is important to understand, that at that time parallel church structures were not formally established, and in reality the Church was single. Therefore, it was very important which bishop, Orthodox or Arian, would occupy one or another see, and what teaching would be adopted at local and especially universal Councils of the episcopate.

This influenced the decision of Basil, who appointed Amphilochius as bishop, knowing about his true Orthodoxy and the impeccability of “a good reputation with outsiders” (1 Tim. 3:7).

Basil and Gregory of Nazianzus, as well as Amphilochius, were from Cappadocia. Therefore, collectively they are called the great Cappadocians. Moreover, Amphilochius was Gregory’s cousin. With him, as well as with Basil, in addition to the theological communion of the Orthodox faith, they were connected by genuine friendship. So, even most of the information about the biography of Amphilochius was preserved for us in their correspondence.

Before the accession of Theodosius the Great (†395) in 379, the children and successors of Emperor Constantine, as well as the metropolitan episcopate, stood on the side of Arianism. Probably, the rulers saw in the absolute monarchy of God the Father a prototype of their autocracy, and influential bishops considered it as the guarantee of a harmony of secular and spiritual authorities.

The doctrinal victory over Arianism was largely ensured by the works of Basil the Great. He was the Archbishop of Caesarea Cappadocia – the Church Metropolis, the influence and jurisdiction of which at that time, in fact, were equal to the prerogatives of a modern local Church.

However, Basil exhausted himself in episcopal labours and died in 379, having lived only 49 years. The work of his life, the Second Ecumenical Council of 381, took place without him.

Saint Amphilochius is an undoubted pillar of Orthodoxy, one of the Fathers of the Church, a prophetic personality. His memory should be prayerfully revered. Without the dogmatic and practical efforts of Amphilochius, the cause of Basil of Caesarea in the struggle for Orthodoxy and opposition to the Arianism heresy might not have triumphed.

INSPIRATION of the SAINTS

In our collective imagination, God appears to be quite old. This corresponds to the icon of the so-called New Testament Trinity, where the Son of God Jesus Christ is symbolically blessed by God sitting on the royal throne as an old man. Moreover, it is in this icon that the “old age of God” is emphatically old. “I finally saw that thrones were set up; and the Ancient of Days sat down: His robe was white as snow, and the hair of His head was like pure wool; His throne is like a flame of fire, His wheels are like blazing fire” (Dan. 7:9), as it is written in the book of the prophet Daniel.

This generally accepted idea of the absolute old age of God is echoed by metaphysics. At the same time, it goes its own way. The God of Philosophy is inaccessible to man. He is invisible, incomprehensible. He is not limited by anything. These are the basic settings with which any seminarian begins the study of dogmatics.

At the same time, in the light of 21st century theology, it is obvious to us that all these extremely lofty definitions of God are one-sided. They act only in one direction. They only apply to us people. After all, we are limited and mortal. God, in Christ Jesus, makes Himself accessible and limited for our sake.

He, according to the words of one of the medieval theologians, took upon Himself all of ours and gave us all His. In the Eucharist we partake of this mystery.

“The length of our days is seventy years – or eighty, if we have the strength; yet their span is but trouble and sorrow, for the quickly pass, and we fly away,” says the Psalms (Ps. 90:10).

Over the years, a person becomes wiser, their behaviour and morals become better. Suffering and illness ennoble and teach understanding. At a biblical level of understanding, these words are true. But at the everyday level, they turn out to be generally accepted stereotypes, which are refuted by reality itself.

Over the years, a person becomes embittered. Habits are cemented by experience. At old age, only family can truly love a person. In this sense, the secular prophet of our times, Steve Jobs, was right when, in his Stanford speech, he argued that the brevity of human life is, in fact, a blessing for others.

New Testament thinking allows us to agree with this, and, at the same time, to think further and deeper. We are used to seeing God as older than us. In popular piety, for centuries and even millennia, He was represented as an old man. This perception can be helpful, but it can also be harmful. Because it hides meanings from us.

“Late did I love You, Beauty, so ancient and so young, late did I love You,” St. Augustine writes about God (354–430). This ancient thinker, who was a bishop of the North African Carthaginian Church, is credited by the history of philosophy with the invention of the very idea of time. Speaking about time and the temporality of man, Augustine turns to the thought of God and claims that among all living beings He is the youngest. God is young. He renews existence. He is younger than each of us and younger than everything in the world.

This paradoxical statement of theological thought reveals many meanings. It turns out that in true youth there is godlikeness. It is present in the desire to learn, in the idealism and romanticism of the perception of ordinary things. The willingness to selflessly change this world for the better was the inspiration of the saints. Faith manifested itself in them in the ability to constantly create themselves anew for the benefit of their neighbours. “Reverence for life,” as Albert Schweitzer (1875–1965) once wrote. This godlike youth of God inspired the ancient saints whom the Church remembers in these autumnal times.