Dramatic events associated with the Philosophers’ Ship occupy a special place in Russian history

By Anatoly Tereshchenko, writer, author of the book, Secrets of the Silver Age

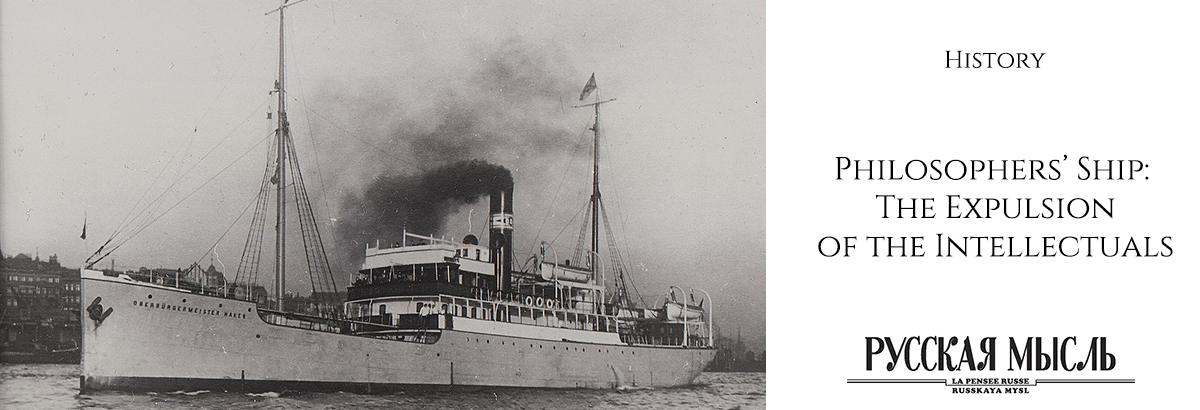

The Philosophers’ Ship should be considered in the literal and figurative senses. Literally, in 1922 two German ships, Oberbürqermeister Haken (29–30 September) and Preussen ‘Prussia’; 16–17 November), transported from Petrograd to the port of Szczecin over 160 people from among the scientific and creative intelligentsia. Deportations were also carried out by ships from Odessa and Sevastopol and by trains from Moscow to Latvia and Germany.

The deportation on the so-called ‘Philosophers’ Ship’ in the early 1920s dragged on for several months for various reasons. There was an ongoing search for prominent scientists, economists, doctors, writers and philosophers. The fact is that many had changed their place of residence because of the Civil War slaughters in large cities, hunger and cold in flats and hidden in villages with their relatives. They were to be found and prepared for exile.

Thus, a virtual vivisection of the Russian culture of that time was carried out, which led to irreparable losses and the degeneration of the gene pool.

It is believed that over 200 people were subjected to expulsion abroad from Russia, and if taken with their families – up to 500. And those who for some reason remained in their homeland were subjected to repressive measures that inculcated in them loyalty to the authorities, and any objection turned into a form of suicide.

From 1918 on Russian universities and institutes were obliged to admit first of all members of the Communist Party, employees of Soviet institutions and people of proletarian origin, even if they had no document on secondary education.

By a decree of the Council of People’s Commissars all university academic degrees were abolished, and the departments of law, history and philology were closed. Twenty-seven well-known professors of Russian universities were shot by the Bolsheviks for ‘anti-Soviet views’, including the world-famous chemist, Professor Mikhail Tikhvinsky.

A little-known fact: in 1922, six professors at Moscow University, including the Dean of the Department of Physics and Mathematics Vsevolod Stratonov, sent an open letter to Lenin and Trotsky. In it they stated that under the Bolsheviks Russian science eked out a miserable existence. There was nothing to treat and work with. Teachers were not paid for months. Sixty-three prominent Russian scientists and ten out of forty Russian academicians had starved to death and some in despair had committed suicide.

“Germany is not Siberia, but how terribly difficult it was to break away from the roots, from a very essence, which boils down in one short word: Russia”.

Nikolay Lossky, Russian philosopher

Having read the letter, Lenin commanded his secretary: ‘Include Dean Stratonov in the expulsion list.’

Europe regarded the expulsion of scientists and cultural figures as an unexpected and generous gift from the Bolsheviks.

Finding themselves in exile against their will, many scientists, politicians and writers immediately plunged into the hectic creative life of the Russian diaspora. They were actively involved in public work, published their own newspapers and magazines, on the pages of which they published articles, memoirs, notes and letters, lectured at higher educational institutions, thus introducing the West to Russian culture.

According to available information, before the outbreak of World War II, scientists expelled from Russia had published over 13,000 research works in the West in all branches of knowledge, seriously advancing scientific and academic developments.

The political castration of the scientific and creative elite naturally had a negative impact on the country’s progressive development.

True, an insignificant number of commanders continued to serve in the Army and Navy, and in industry – some engineers who had graduated from higher educational institutions before the Revolution. It was they who would later be called ‘specialists’, but these specialists, seeing the lack of prospects in the country’s development, insisted in the early 1930s on the purchase of over 200 plant projects from abroad, on the basis of which they were then able to create more or less modern military equipment.

Stalin turned out to be more perspicacious than Lenin in this matter. As Yuri Chashin wrote in his article, Lenin’s Philosophers’ Ship and Our Losses: ‘Here is the price of the decisions of a half-educated from Simbirsk, the brother of a terrorist and regicide, who walked another way – that of not only the destruction of the Tsar, but the extermination of the whole people… It would be as if someone now dared to attack modern China. After all, there are no suicides in politics. But the Russian scientists exiled by Lenin had to work for the benefit of the peoples of other countries. Most of them succeeded and left behind scientific schools in Europe and America.’

The most famous passengers of philosophical ships

Berdyaev Nikolai Alexandrovich (1874–1948), a Russian religious philosopher, publicist and public figure.

Bulgakov Valentin Fedorovich (1886–?), a head of the Tolstoy house-museum, writer.

Bulgakov Sergey Nikolaevich (1871–1944), an Orthodox theologian, philosopher, publicist, economist and public figure.

Ilyin Ivan Alexandrovich (1883–1954), a lawyer and religious philosopher.

Karsavin Lev Platonovich (1882–1952), a historian-medievalist, philosopher and theologian.

Kizevetter Alexander Alexandrovich (1867–1933), a historian, thinker, professor of Moscow University, member of the Cadets Party.

Lossky Nikolai Onufrievich (1870–1965), a philosopher, representative of intuitionism and personalism.

Osorgin (Ilyin) Mikhail Andreevich (1878–1942), a writer and publicist; freemason.

Prokopovich Sergey Nikolaevich (1871–1955), an economist, politician; freemason.

Sorokin Pitirim Aleksandrovich (1889–1968), a philosopher, sociologist, one of the founders of American sociology.

Stepun Fyodor Avgustovich (1884–1965), a publicist and philosopher.

Trubetskoy Sergei Evgenievich (1890–1949), a politician, scientist.

Frank Semyon Ludwigovich (1877–1950), a philosopher.

Yasinsky Vsevolod Ivanovich (1884–1933), a doctor-engineer, mechanical engineer, professor at the Higher Moscow Technical School.

An example is the activity of an aircraft designer, ‘the father of the world helicopter industry’, Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky, though he had been pushed out of Soviet Russia by negative circumstances a little earlier. Various, unexpected achievements of design ideas are associated with his name, each time bringing world aviation to a new level.

And the Philosophers’ Ship took abroad hundreds, if not thousands like him. What Sikorsky did for France and the USA he could have done for Russia…