Charitable activity reached its peak in Russia in the late 19th and early 20th century

Karina Enfenjyan

In the Russian Empire, patronage began to grow actively in the 18th century, during the reign of Empress Catherine the Great, and at first it was exclusively the prerogative of the nobility. Aristocrats were fond of collecting works of art and, like the Roman patrician Gaius Maecenas, patronised talented artists, poets and musicians.

Charitable activity was a duty of honour for the nobility: members of noble families donated vast amounts of money to support education, science, culture, arts, and literature.

A large historical footprint was left in Russia by patrons and collectors descending from the noble Stroganov family. Already in the 16th and 17th century, they patronised the most skilled icon painters and talented architects, entrusting them with the construction of churches. Count Alexander Sergeyevich Stroganov (1733–1811) was an outstanding patron of the arts. He was appointed President of the Imperial Academy of Arts and director of the Imperial Public Library by decree of Paul I. Artists, composers, poets, and among them Derzhavin and Krylov, enjoyed his support.

A rich collection of books, manuscripts, coins and historical documents amassed by the prominent statesman and philanthropist, Count Nikolay Petrovich Rumyantsev (1754–1826), who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia during the war against Napoleon, laid the foundation for the Rumyantsev Museum, on which basis the public library (currently the Russian State Library) was established.

A highly educated representative of one of the most noble Russian families, a favourite of Paul I, Count Nikolai Petrovich Sheremetev (1751–1809) went down in history as a patron of the arts, a collector, patron and philanthropist, as well as an outstanding theatrical figure and founder of the Hospice in Moscow, where the N. V. Sklifosovsky Research Institute for Emergency Medicine is now located.

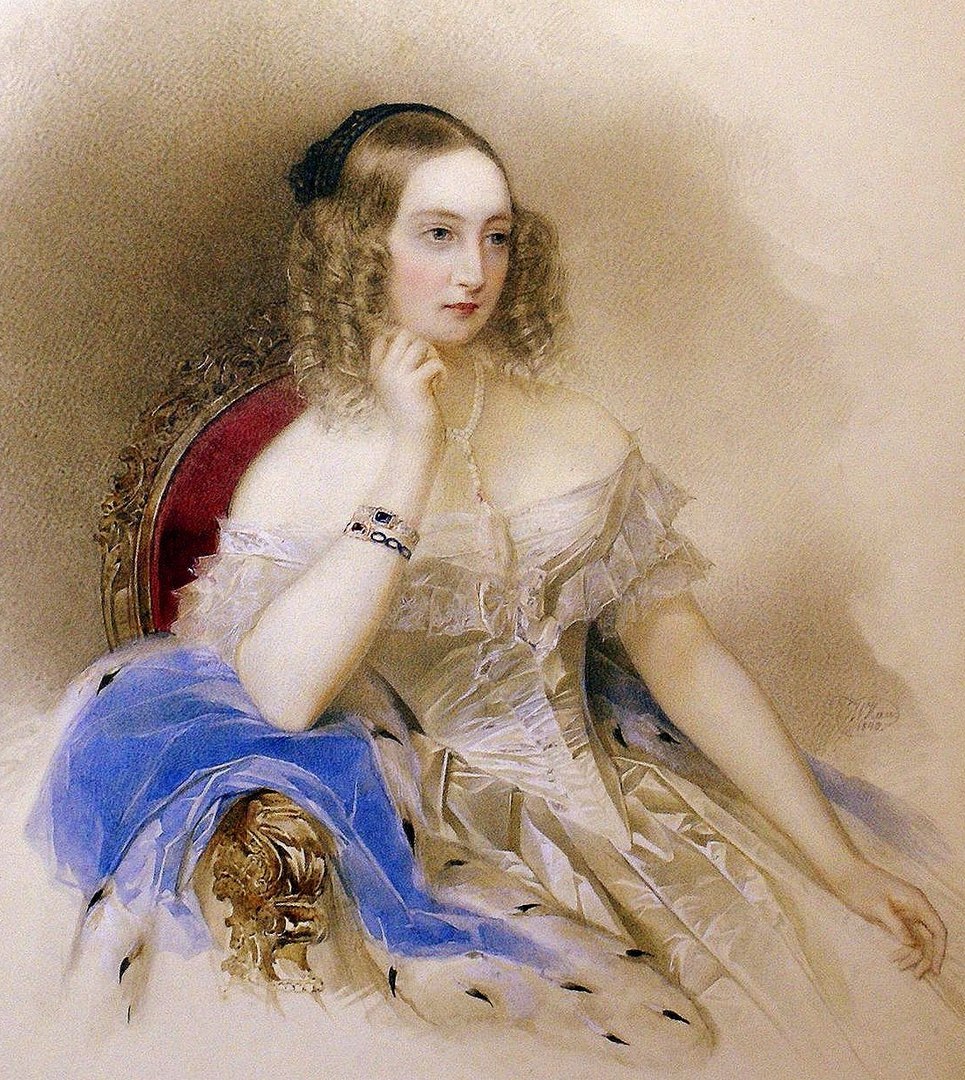

Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (née Princess Friedericke Charlotte Marie of Württemberg, 1806–1873), wife of the Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich, a supporter of the abolition of serfdom, patronised such outstanding artists as Ivan Aivazovsky, Karl Bryullov, Alexander Ivanov, as well as talented actors and scientists. She financed the establishment of the Russian Musical Society and conservatory, participated in the organisation of the world’s first sodality of sisters of mercy to help the wounded during the war. All this way before the establishment of the Red Cross.

Imperial Russia saw many noble philanthropists, and it’s close to impossible to list them all. With the establishment of capitalist relations in the country, the merchants began to establish themselves more and more confidently, striving to be equal to the nobility.

Over time, not only the aristocracy and the clergy, but also representatives of the bureaucracy and merchants began to take part in the creation of charitable institutions; as far as possible, artisans and peasants also contributed to them.

The abolition of serfdom in 1861, the rapid development of industry and trade promoted the emergence of talented entrepreneurs among ordinary people.

Charitable activity reached its peak in Russia in the late 19th and early 20th century, where merchants played a huge role.

In addition to the fact that many successful entrepreneurs sincerely considered charity as their moral duty and strove to live like a Christian, philanthropy and patronage were also an indicator of their social position, their way to express themselves.

In addition, the owners of large industrial enterprises needed qualified personnel capable of working on the state-of-the-art equipment, which was important in an increasingly competitive environment.

Great opportunities opened up for philanthropists, such as support for education and educational institutions, to which special attention was then paid, assistance to talents in science, culture, arts, literature, regardless of their estates origin.

Among the most generous patrons in pre-revolutionary Russia, whose contribution to the development of Russian science, arts and education can hardly be overestimated, were Pavel Tretyakov, who amassed an invaluable collection of Russian art and discovered the Itinerants for the world; Savva Mamontov, patron of Vasnetsov, Polenov, Korovin, Serov; Savva Morozov, who made a great contribution to the development of theatrical art in Russia; Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin with their unique collections of French Impressionists; Alexey Bakhrushin, founder of the first Moscow Literature and Theatre Museum.

We will delve into the lives and charitable activities of these prominent representatives of pre-revolutionary Russia in this issue of our magazine, but first we would like to recall the wise saying of Leo Tolstoy: “I became convinced that one cannot be a philanthropist without living the good life, moreover, one cannot – while living the bad life, while taking advantage of the conditions of that bad life – decorate his bad life, just visiting the field of charity. I became convinced that charity can only satisfy both personal and external requirements, when it unavoidably arises from the good life; and that the requirements of such good life are very far from the conditions in which I live. I became convinced that the opportunity to do good to people is the crown and the highest reward of the good life, and that in order to achieve this goal there is a long ladder, on the first step of which I did not even dream to enter. You can do good to people only in such a way that not only others, but also yourself would not know that you are doing good, so that the right hand does not know what the left is doing; only as it is said in the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles: so that your alms sweats out of your hands, so that you do not know to whom you give. You can do charity only when your whole life is serving the good. Charity cannot be the goal itself – charity is the inevitable consequence and fruit of the good life.”