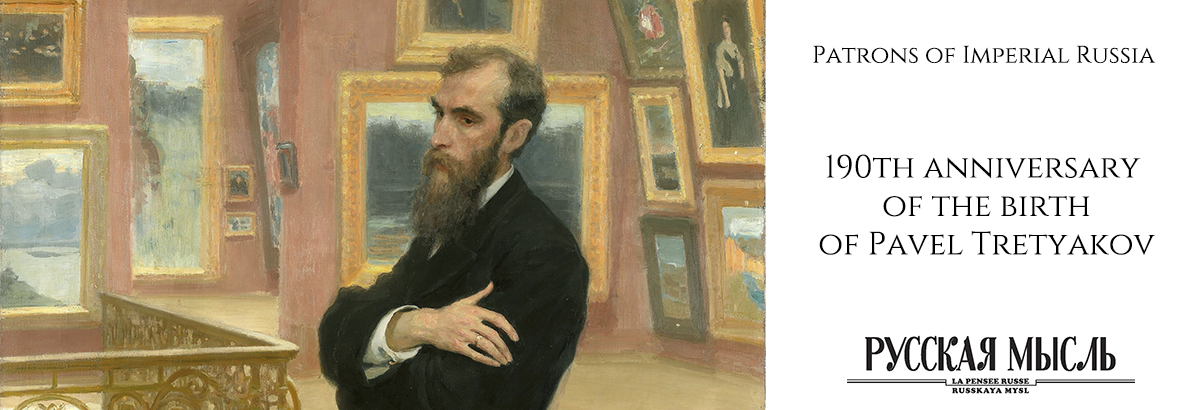

History has preserved the names of thousands of people for whom patronage of the arts, charity and selflessness were not alien, and one of them was Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov

By Alexander Khodorenko, a writer, author of the book, Ten Geniuses of Business

The Tretyakovs came from an old but not wealthy merchant family dating back to 1646. Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov’s great-grandfather – Yelisey Martynovich – moved to Moscow from the town of Maly Yaroslavets [now Maloyaroslavets]in 1774. His grandfather – Zakhar Yeliseyevich – was a Moscow merchant of the 3rd Guild. In 1828, he opened an establishment in Moscow for dyeing and starching canvas and sailcloth. His father – Mikhail Zakharovich, a Moscow merchant of the 2nd Guild – managed to expand the family business. But the Tretyakovs’ business did not reach a truly great scale until the next generation. Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov inherited his father’s business in the first half of the 1850s. The ‘Brothers P. and S. Tretyakov and V. Konshin’ trading company appeared in Moscow in 1860. Tretyakov’s sons continued trading and industrial business. In 1864, they founded the New Kostroma Linen Mill, built several flax-processing factories in Kostroma, and two years later established the famous Association of the Large Kostroma Linen Mill with a capital of 270,000 gold roubles.

It should be noted that Pavel Mikhailovich spent about 1.5 million roubles on organising an art gallery in Moscow. He received over a third of this amount in the form of profit from the New Kostroma Linen Mill. Thus, the Kostroma textile workers contributed to the creation of a national treasury – the famous Tretyakov Gallery.

The Tretyakov factory was considered one of the most advanced and best equipped in Russia. Pavel Mikhailovich also tried to improve the living conditions of its workers. A school, a hospital, a maternity hospital, a nursing home and a nursery were built for them.

Expanding their father’s business, the Tretyakov brothers also built cotton factories, which employed about 5,000 people.

When creating his famous gallery, Pavel Mikhailovich spent enormous amounts of money, perhaps to the detriment of his own family’s well-being. And he had a large family. In 1865, Pavel Mikhailovich married Vera Nikolaevna, nee Mamontova, a cousin of Savva Ivanovich Mamontov, a famous Russian entrepreneur, industrialist and philanthropist, the founder of the Moscow Private Opera, and the great-aunt of another Vera Mamontova, who was the model for the painting ‘Girl with Peaches’ (1887) by V. A. Serov. They had six children – two boys and four girls.

- S. Turgenev, the composers N. G. Rubinstein and P. I. Tchaikovsky, the artists I. E. Repin, V. I. Surikov, V. D. Polenov, V. M. Vasnetsov, V. G. Perov and I. N. Kramskoy would visit the Tretyakovs. The family was related to some of them: P. I. Tchaikovsky’s brother Anatoly was married to Pavel Mikhailovich’s niece; the artist V. D. Polenov’s wife, N. V. Yakunchikova, was Vera Nikolaevna’s niece.

Pavel Mikhailovich, a fourth-generation merchant, wanted his daughters to marry only merchants. But it so happened that his eldest daughter, Vera, fell in love with the talented pianist Alexander Siloti, the composer S. V. Rachmaninoff’s cousin. Knowing that her father might not give her his blessing to marry a musician, Vera was very nervous and even fell ill. When Pavel Mikhailovich saw his daughter’s suffering, all his theories regarding his daughters’ life partners failed.

The wedding of Vera Tretyakova and Alexander Siloti took place in February 1887. Alexandra (another daughter) married the doctor and collector Sergey Botkin. His brother Alexander, a doctor, later a hydrographer and an explorer of the North, married Masha. In May 1894, Lyuba married the painter Nikolay Gritsenko. Widowed in 1900, she remarried – her second husband was the famous Leon Bakst, a painter and a designer who created costumes and scenery for Diaghilev’s ballet in Paris. Pavel Mikhailovich had enough breadth of vision to appreciate all these young men.

The following fact can testify to the way Tretyakov brought up his daughters. In 1893, Pavel Mikhailovich wrote a very large and serious letter to his daughter Alexandra, in which he explained his idea of parental duties: ‘Money is not a good thing which causes unhealthy relations. Parents must bring up their children and give them education, but they are not at all obliged to provide for them.’ There were the following words in the same letter: ‘My idea was to make money from a very young age so that what was received from society would also return to society (the people) in some useful institutions; This idea has never left me all my life.’

Fascinated by art, in 1854 Tretyakov began to collect pieces of national Russian works of art. His first acquisitions – about ten graphic sheets of old Dutch painters – were bought at a flea market near the Sukharev Tower. These drawings adorned his living-rooms until his death.

At first lacking experience and multifaceted knowledge in the sphere of art and guided by a deep patriotic feeling, Tretyakov decided to focus on collecting works by contemporary Russian artists. It is known that Pavel Mikhailovich had no special art education. Nevertheless, he bought works by his still little-known yet talented contemporaries. As a rule, he acquired the most significant works from this or that artist.

‘A Clash with Finnish Smugglers’ (1853) by V. G. Khudyakov was one of the first paintings acquired by Tretyakov in 1856. That year marked the birth of the Tretyakov Gallery. This was followed by the purchase of works by I. P. Trutnev, A. K. Savrasov, K. A. Trutovsky, F. A. Bruni, L. F. Lagorio and others. Knowing about works by K. P. Bryullov in Italy, Tretyakov asked permission from the archaeologist M. Lanci’s children to purchase his (Lanci’s) portrait. Thus, in 1860, the first work by the ‘great Karl’ (Bryullov) – ‘Portrait of the Archaeologist M. Lanci’ (1851) – appeared in the collection. So Tretyakov began selfless collecting work that lasted for many years. It was modest and not designed for advertising and praise. We can say that from the very beginning he had a clear idea of the purpose of his undertaking.

Pavel Mikhailovich pursued no selfish goals. He came up with the idea of creating a museum of national paintings. In his will, drawn up in 1860, just four years after the purchase of the first paintings, he wrote: ‘For me, who genuinely and ardently loves art, the greatest wish is to lay the foundations for a public repository of fine art, accessible to all, to the benefit of many and pleasure for all.’

Tretyakov’s confidence and faith in his cause seem surprising if we remember that he laid the foundations of the gallery at a time when the school of Russian art as an original and significant phenomenon loomed only faintly in the shadow of the great tradition of the West; mighty ancient Russian art had been half-forgotten, works by Russian artists were in private collections in Russia and abroad; when there were still no Repin, no Surikov, no Serov, no Levitan and their paintings, without which it is impossible to imagine Russian art today. It was the time of the formation of democratic art and the birth of a new school of Russian art.

‘…Without his help Russian art would never have entered an open and free phase, since Tretyakov was the only (or almost the only) one who supported everything that was new, fresh and practical in Russian art’ (A. Benois).

There were few real enthusiasts in old Moscow who took an active part in the lives of young artists. They mostly just bought paintings for their galleries, and sought to pay less for them. Unlike them, Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov was a real patron of arts. His visits to artists were always considered as exciting events, and all of them, masters and beginner artists, with awe waited for his quiet words: ‘I am going to buy your painting,’ which was tantamount to public recognition for everyone. In 1877, Repin wrote to Tretyakov about his painting ‘Protodeacon’: ‘I confess to you that if I sell it, then only to you, to your gallery, because, I say without flattery, I consider it a great honour to see my works there.’ Artists often made concessions to Tretyakov (he never bought paintings without bargaining) and lowered their prices for him, thereby providing all possible support to his undertaking. And the benefits were mutual. Pavel Mikhailovich not only bought paintings, but also ordered them, thus supporting artists both morally and financially, which allowed them not to depend on the tastes of the market.

In the activities of Tretyakov the collector’s attention was primarily focused on works by contemporary realist painters of the mid and second half of the nineteenth century – the Wanderers (the Itinerants), representatives of the democratic wing of the national school, which defined the originality of the gallery’s collection, the influence of this collection on the development of realist art, and its progressive, revolutionary and educational impact. But in the 1860s, when the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions still did not exist, Tretyakov bought paintings in the official ‘academic’ style, and from the late 1880s – works by M. V. Nesterov, K. A. Korovin, V. A. Serov and others. Then Tretyakov began to collect drawings, and in the 1890s – icons.

Tretyakov had unmistakable taste. He was not afraid to buy works by young, still unknown artists. The specifics of the way Pavel Mikhailovich collected paintings are seen in the fact that many works for the gallery were done at his request. And neither then nor today do these works disappoint the most demanding connoisseurs of Russian art with their problems or artistic merits. He bought works even when figures of high authority like L. N. Tolstoy, who did not recognise V. M. Vasnetsov’s religious paintings, opposed it. He even bought paintings that were banned by the imperial authorities for public viewing.

Pavel Mikhailovich acquired paintings at exhibitions and right in the studios of artists. Sometimes he bought entire collections: in 1874 he acquired the Turkestan series by V.V. Vereshchagin (thirteen paintings, 133 drawings and eighty-one sketches), and in 1880 – his Indian series (seventy-eight sketches). There were also over eighty sketches by A. A. Ivanov in Tretyakov’s collection. In 1885, Tretyakov bought 102 sketches by V. D. Polenov, done by the artist during a trip to Turkey, Egypt, Syria and Palestine. From V. M. Vasnetsov Pavel Mikhailovich acquired a collection of sketches that he had done while working on murals in St Vladimir’s Cathedral in Kiev. V. G. Perov, I. N. Kramskoy, I. E. Repin, V. I. Surikov, I. I. Levitan and V. A. Serov were represented in his collection most fully and by their best works. The gallery was replenished with works by artists of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth centuries and monuments of ancient Russian art. This heroic period of Russian art can be understood, felt keenly and explored in Moscow, in the Tretyakov Gallery, more than anywhere else.

All artists, young and famous, dreamed of having their paintings hung at the Tretyakov Gallery because the very fact of buying a painting by Pavel Mikhailovich was an act of public recognition of an artist’s talent. So one marvellous man managed to influence all Russian pictorial art and become a spokesman for Russian public opinion.

Tretyakov’s great merit is his unshakeable faith in the triumph of the Russian national school of painting – a faith that arose in the late 1850s and was carried by him through his life, through all the trials and tribulations. We can say with confidence that in the late nineteenth century P. M. Tretyakov’s personal contribution to the triumph of Russian pictorial art was exceptional and invaluable.

Evidence of his ardent faith has been preserved in Pavel Mikhailovich’s letters. Here is one of them. In a letter to the artist Rizzoni dated 18 February 1865, he wrote: ‘In the last letter to you my expression might seem incomprehensible: “Then we would talk with skeptics.” I will explain: many positively do not want to believe in the good future of Russian art and argue that if some Russian artist sometimes does a good painting, it is allegedly by accident and he will increase the number of mediocrities. I have a different opinion, otherwise I would not have collected Russian paintings; but sometimes I could not but agree with the facts presented; and every success, every step forward is very dear to me, and I will be very happy if I live to see when our day comes.’ And about a month later, returning to the same thought, Tretyakov wrote: ‘I involuntarily believe in my hope: our Russian school will not be the worst – it was indeed a clouded time, and for quite a long time, but now the fog is lifting.’

His faith was not a blind intuitive feeling: it was based on careful observation of the development of Russian pictorial art, on a deep, subtle understanding of national ideals that were being formed on a democratic basis.

So, back in 1857, Pavel Mikhailovich wrote to the landscape painter A. G. Goravsky: ‘Concerning my landscape, I humbly ask you to leave it, and instead paint me a new one someday. I need neither rich nature, nor a great composition, nor spectacular light, nor miracles.’ Instead, Tretyakov asked him to depict simple nature, even if unprepossessing, ‘but there must be truth and poetry in it. And poetry can be in everything – this is the artist’s work.’

This note expresses the very aesthetic principle of the formation of the gallery, which emerged as a result of reflecting on the development of Russian national pictorial art. P. M. Tretyakov had guessed its progressive tendencies long before the appearance of Savrasov’s painting ‘The Rooks Have Come Back’, the landscapes by Vasiliev, Levitan, Serov, Ostroukhov and Nesterov – the artists who managed to create a truthful depiction of Russian nature, conveying the poetry and charm inherent in it.

Pavel Mikhailovich first entrusted the idea of creating a national or folk art gallery to the artist V. G. Khudyakov and outlined it with the utmost accuracy in a testament written in Warsaw on 17 (29) May, 1860, during his first trip abroad.

His relatives did not have to execute this will. Pavel Mikhailovich himself fulfilled his dream – he set up a folk-art gallery.

Interesting statements by P. M. Tretyakov can also be found in his correspondence with Vereshchagin regarding the depiction of the contemporary Russo-Turkish war of 1877–1878 for the liberation of Bulgaria – a war in which Russia took Bulgaria’s side. On learning that Vereshchagin was going to the front to do a series of paintings about the war, Tretyakov wrote to the critic of music and art V.V. Stasov: ‘Perhaps only in the distant future will the sacrifice made by the Russian people be appreciated.’

Tretyakov suggested that Vereshchagin pay a large sum in advance for his work: ‘However strange acquiring a collection without knowing its contents may be, Vereshchagin is a kind of artist you can rely on, especially since giving paintings over to private hands, he will not be bound by choosing subjects and, probably, will be imbued with the spirit of the sacrifice of people and the brilliant heroic deeds of Russian soldiers and some individuals.’

Vereshchagin had a different opinion: ‘As for your letter to V.V. Stasov on my painting you saw, you and I obviously disagree a little in the assessment of my works and a lot in their trends. There is war before me as before an artist, and I strike at it with all my might; whether my blows are strong or real – this is a question of my talent, but I fight with all my strength and mercilessly…’

In addition to collecting, Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov was actively involved in charity work. He was an honorary member of the Russian Society of Art Lovers and the Russian Musical Society from the day they were founded and contributed substantial sums, supporting all educational initiatives. He provided material assistance to individual artists and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture; from 1869 he was a member of the Council of the Moscow Trust for the Poor. He was also a member of the councils of the Moscow Commercial College and the Alexander Commercial College. Pavel Mikhailovich bequeathed half of his funds to charitable purposes: to set up a shelter for widows, young children and unmarried daughters of deceased artists (it was built in 1909–1912 by the architect N. S. Kurdyukov in Lavrushinsky Lane); for distribution among workers and employees of his enterprises; and for funding the gallery. He gave donations to help the families of soldiers who had fallen in the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish (1877-1878) War. P. M. Tretyakov scholarships were established at the Moscow Commercial College and the Alexander Commercial College.

Pavel Mikhailovich never refused to render financial aid to artists and other applicants. He took good care of the money affairs of painters who entrusted their savings to him with confidence. He repeatedly lent money to his good adviser I. N. Kramskoy, selflessly helped V. G. Khudyakov, K. A. Trutovsky, M. K. Klodt and many others.

Brothers Pavel and Sergey Tretyakov founded the Arnold-Tretyakov Deaf-and-Dumb School in Moscow. Pavel Mikhailovich took his establishment very seriously. At first classes with deaf-mute children in live speech were rather primitive, and Pavel Mikhailovich sent the headmaster D.K. Organov abroad at his own expense so he could familiarize himself with the teaching process in similar schools. In addition to general subjects, children were taught crafts. The school, or the ‘institution for the deaf-mute’, obtained a large stone house with a huge garden, where 156 pupils of both sexes studied and lived, and in the early 1890s Pavel Mikhailovich built a hospital with thirty-three beds at his own expense.

Patronage of the school, which began in the 1860s, continued throughout Pavel Mikhailovich’s life and after his death. In his will Pavel Mikhailovich left very generous funds for the school for the deaf and dumb. Boys and girls would be brought up till the age of sixteen and receive a profession. Tretyakov selected the best teachers, got acquainted with the teaching methods, and made sure that the pupils were well fed and clothed. On each visit to the school he went round the classes and workshops during class hours and was always present at exams.

In 1871, on the initiative of Pavel and Sergei Tretyakov, a passage was built between Nikolskaya Street and Teatralny Passage on the site of an earlier one that had been built up in the eighteenth century. In 1870–1871 the architect A. S. Kaminsky constructed two buildings with passage arches facing Nikolskaya Street and Teatralny Passage on the site purchased by the Tretyakovs especially for the arrangement of the passage; the facade of the building from the side of Teatralny Passage was built into the Kitay-Gorod Wall next to the tower (1534–1538) and designed in a romantic-medieval style. There were shops inside the passage. Such urban planning solution is unique for Moscow. The new structure was called Tretyakov Drive.

The Explanatory Dictionary defines charity as ‘gratuitous actions and deeds whose aim is the public good.’ With reference to the life of Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov we can add: ‘and which will never be forgotten.’