Few people know that in the original Greek Creed the word “Creator” literally means “Poet”

Augustin Sokolovski, Doctor of Theology, Priest

At the Liturgy of the second preparatory Sunday before Lent, following the ancient Church rule regarding the order of Gospel readings, the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32) is read.

This parable of the Lord Jesus is found in the Gospel of Luke and is not found in the other Gospels. It reveals the essence of gospel forgiveness. In pondering the mystery of forgiveness, the Church as a community of the faithful prepares itself in this way for the Lenten season. In the language that we use for spiritual things, words creep in that become meaning-neutralizing. They are so familiar that they can block understanding.

When we speak of “chief priests”, for example, in reference to those who held supreme sacred authority in the time of Christ, we are often unaware of the greatness and authority that these men were called to possess, who in the end betrayed their Biblical calling and condemned the Lord. At the words “tax collectors”, “harlots”, and “sinners” we may fail to feel all the censure and condemnation that fell upon Christ for their fellowship with them. Finally, when we call a lost, lost, perished, torn, lonely, doomed son simply a “prodigal son”, we cease to understand God.

For centuries, and now for millennia, interpreters, preachers, counselors, moralists have offered their own, so many, but incredibly similar explanations for the parable of the prodigal son. And we just haven’t noticed that theology has long since moved on. Ran away. Gone. From countless books and speeches “about God” it has, in Eucharistic terms, “transmuted” into Art, Thought, Literature. After all, the greatest theologian of the twentieth century was … no, not a teacher or a hierarch, but … the writer Franz Kafka; the greatest Russian theologian was Dostoevsky.

Everyone remembers the magnificent realistic paintings of Flemish masters on biblical themes. And no one will ever forget Rembrandt’s The Prodigal Son. And the stunning, incomparable moral pathos of Russian literature, in its essence, and by virtue of its incredible hidden theological tectonics, is nothing other than an appeal, a plea to believe that what Jesus said in the Parable of the Prodigal Son is true.

The Parable of the Lord shows us the face of God. His kind, wonderful, harmless, native and familiar, blindfolded face. Only He can forgive without knowing. He has biblical power, right and authority to do so. The Kingdom, and the Power, and the Glory. The Parable of the Prodigal Son by the mouth of the Lord Jesus speaks of forgiveness. It speaks about how God cannot fail to forgive. But the same Gospel also tells us that there is a sin that is not forgiven: blasphemy against the Holy Spirit. The truth is that no one has ever been able to answer the question of what such blasphemy is. God remained elusive in His word. “But the older son became angry and would not come in. And he answered his father, ‘When this son of yours, who wasted his possessions, came in, you made a feast for him'” (cf. Luke 15:28–30). The end of the Lord’s parable – the sinful appearance of the righteous, blameless, judgmental son – has revealed to us the Face of the Antichrist and it’s the key to understanding that ‘blaspheming the Spirit’ is Unforgiveness. The sin of the one who does not allow forgiveness. Judgment on him who is forgiven. Judgment on him who forgives.

***

During the first days of Great Lent, the great penitential canon of St Andrew of Crete (660–740) is read at the Vespers service. This four-day reading introduces the Church to a time of repentance. In reading the great canon, the Church also honors the memory of its venerable author. Saint Andrew was born at Damascus during the reign of the fourth righteous caliph of Islam, Ali (656–661), whose succession is referred to in the Islamic Shi`a tradition, and died on the island of Lesbos during the reign of the Iconoclast emperor Leo Isaurus (+741), who ushered in a new Constantinopolitan dynasty. The birth of Andrew was a year before the tragic death of Imam Ali, and his departure to the Lord also was a year before the death of Leo.

The era of the Righteous Khalifs (630–661) came to an end with the death of Abu Talib. It was Leo who succeeded in stopping the Arabs’ advance at the walls of Constantinople (718). And in gratitude to God for this victory, Leo has begun … Iconoclasm (730–842). Unlike the hagiographies of many famous saints, there is little legendary in the extant biography of Andrew. His biography is interesting and logical. Though it is deprived of the legendary, it is historical and therefore precious and instructive.

Early enough, at the age of 15 Andrew settled in the monastery of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. According to the canons of the Church, the age of majority sets at 14 years. And in general, people’s life expectancy was low at that time. In 680 the III Council of Constantinople was held in Constantinople, which later went down in history as the VI Ecumenical Council. At this Council the Church condemned the heresy of Monothelitism. Monotheletism held that there was no natural human will in the God-man Christ. According to the logic of the Council Fathers, this meant that the human will was not perceived by Christ and therefore not healed. The theme of sickness and healing of the human will is one of the components of … the Great Canon. Since Jerusalem was on Caliphate territory, the Patriarch Theodore I (668–692) didn’t take part in the Council of 680. In 685 he sent Andrew, who had by that time become his secretary, as a member of a delegation to Constantinople to confirm the consent of Jerusalem with the decisions of the Council of Constantinople. Andrew remained in the Capital, where he was made a deacon in the Hagia Sophia.

Like our own, Andrew’s time was an apocalyptic time. In the aftermath of the Christological disputes of the V–VI centuries, following the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon (451), the bigotry of the opponents of the Council and the repressive policy of Constantinople against the dissenters, Eastern Orthodoxy was split into two parts from 537. The centres of these parts were Alexandria and Constantinople respectively. They were two equal churches, with parallel hierarchies, which did not mind … rebaptizing each other. At the beginning of the eighth century the Arab armies were already conquering the Pyrenees, by 674–678 they were already at the walls of Constantinople. In his canon, St Andrew asks the Virgin to preserve the ‘Great City’. New Emperor Leo III Isaurus (717–741) was very religious. In religion he looked for the reason of constant defeats of Byzantines. In 717–718 the second siege of Constantinople by Arabs continued. Leo allied himself with the Bulgarians and he was a great commander. At the cost of unbelievable effort, the city was defended. The victory of the founder of the Isaurian dynasty stopped the Arab expansion in Asia Minor and Eastern Europe. Then in 726 Leo embarked on the path of iconoclasm. After all, the Muslims, who were constantly winning military victories at that time, were also “iconoclasts”, i.e. those who did not accept human religious images. Soon afterwards, Leo began to win. Such a coincidence was a great temptation for the Church at that time.

Andrew was a deacon until his consecration in 692 as bishop of the Cretan city of Gortyna, not far from Heraklion, in the year 692. In 712 he took part in another Council convened by the emperor Philippikos Bardanes (711–713), which reversed the decisions of the Sixth Ecumenical Council and again upheld Monothelitism. For Fathers like Maximus (580–662) or Martin the Confessor (598–655), signing the Council’s decisions in this way meant renouncing Christ. After the deposition of Philippikos, Andrew repented of his earlier decision, it is documented in a corresponding poem. The mourning of the denial of God runs invisibly through the lines of the Great Canon. Shortly before his death, St Andrew of Crete went to Constantinople. As if to atone for his Monothelite renunciation, St Andrew preached against iconoclasm. In 730, together with Patriarch Germanos (+730), St Andrew refused to sign the Iconoclastic Edict. For this he spoke out against the policy of the Emperor. The creator of the Canons was deposed, exiled and died in exile. Andrew had a great poetic gift. Liturgical scholarship believes that Andrew of Crete should be considered the progenitor of the liturgical genre of canons. Historically, the canon superseded the preceding genre of the kondak: an extended, technically and philologically much more complex type of liturgical text of praise in honor of the feast. The pinnacle of the kondak genre is considered to be the work of the native of Homs, Syria, Romanos the Melodist (485–556). In remembering St Andrew of Crete, the congregation is also called to remember his unwitting rival Romanus, of whose great, stunning poetic legacy almost nothing is used in contemporary Orthodox worship…

“I believe in one God the Father, the Almighty, the Creator of heaven and earth.” Few people know that in the original Greek Creed the word “Creator” literally means “Poet”.

Reading the Great Canon, the Church cries out: “Reverend Father Andrew, pray to God for us”. St Andrew was a bishop, a preacher and a poet. The hagiography of St Andrew of Crete tells us that he was not able to speak until he was seven years old. The gift of speech came to him through Communion. It turns out that, in Andrew’s creations, Communion was the birth of poetry – poetry to the glory of the Poet of Heaven and Earth.

***

The third Sunday in Lent is dedicated to the remembrance of the Holy Cross. The approaching of the Sunday of the Cross marks exactly half of the forty-day period, which, according to the ancient Christian tradition, is dedicated to penitence. By analogy with the forty days of repentance, this period is a time of biblical lamentation of man over the imperfections of his soul. The coming of the Sunday of the Cross means that exactly half of those sacred forty days have already passed. There is a belief that, unlike Western Christianity which concentrates on the Cross, the suffering and death of Christ, Eastern Christianity has always been a religion of joy, celebration and resurrection. However, this is not entirely true. For the Cross undoubtedly resides also in the holy of holies of Eastern Orthodoxy.

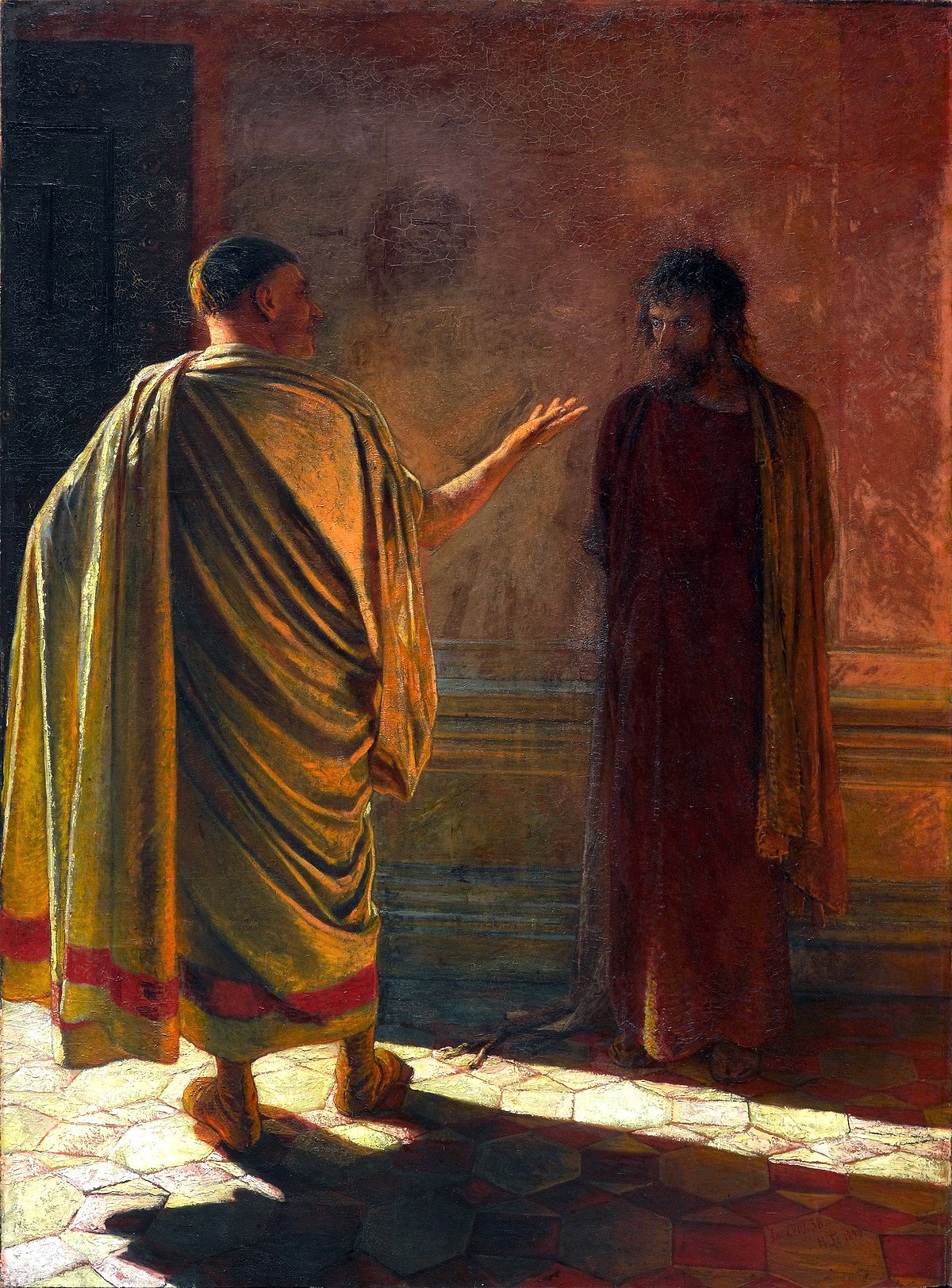

If we try to formulate what is specific about the Cross that distinguishes Eastern Christianity from Western Christianity, perhaps it would be more correct to say that Orthodoxy perceives the Cross as a sign of victory. The triumph of the Risen One over the devil, hell and death, accomplished on the Cross. The Cross of Christ is mentioned in the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, which Tradition identifies with the Second Ecumenical Council of 381. The Cross is mentioned. In doing so, it does not “appear” alone, but accompanied by a historical character – one of the few people in History who saw the Cross of the Lord Jesus with their own eyes. Apart from Jesus and the Virgin Mary, the Gentile Pilate is the only named person mentioned in the Creed. For reasons unknown, he was, as it were, the focus of the drafters of the text. “Crucified for us under Pontius Pilate”. Many commentators thought that Pilate was mentioned only to mark the chronology of the Event of the Cross. Had this been the case, the makers of the Symbol would have had to have included Tiberius (+37), the emperor under whom Jesus was crucified. But, unlike Pilate, Tiberius Augustus did not speak to Jesus, and the extant legends about his involvement in the Lord’s biography apparently already seemed too implausible to the Church at that time. Pilate is not mentioned in the Symbol for chronological reasons. His name is a political decision of the Church to witness to its parity, equality, opposition, interaction, dialogue with the Empire. In the language of theology, it means to express “universality”. With the words of the Crucifixion under Pilate, the Church consciously opposed herself to the political and state world represented in the person of whoever then specifically represented the Empire before the Lord Jesus.

The Church perceived itself as a concrete vis-a-vis the Empire. As something or someone who, until the end of the age, would have a dialogue with it, preaching to its peoples. If we follow this logic, the Church was to live with the Empire forever. “Caesar proclaimed to all men the banner of salvation <…>, in the midst of the royal city he raised up a sacred symbol (of the Cross) against the enemies and inscribed firmly and indelibly that this salvific sign is the guardian of the Roman land and the whole empire” (Praise of Constantine 1:40).

It is interesting that Pilate, who crucified Jesus, immediately, and as it was thought at the time, forever, succeeded in getting away from the responsibility for his crime against the truth. Thus, already in the last chapters of John’s Gospel, there is an obvious attempt to rehabilitate him. “Pilate said to them, ‘I find no fault in him'” (John 18:38). “Pilate, hearing this word, was more afraid” (John 19:8). “From that time Pilate sought to let Him go” (Jn.19:12).

The first centuries of Christianity continued Pilate’s Apologetics. In Tertullian (+220) we find evidence that the washing of hands by Pilate symbolizes baptism. Also, and in one of the synaxaries of the Ethiopian Church, he is mentioned among the saints, with a Memorial Day of 19 June. Among the monuments of this ancient Eastern Church, we find the “Martyrdom of Pilate,” and even the “Anaphora,” which the Eucharistic Prayer apparently attributed to his name … Under the name of Claudia Procula, a martyr venerated in our liturgical calendar, many see the “last dreamer” of the New Testament (Mt.29:17) – the wife of the Roman Procurator of Judea. Pilate managed to keep his hands washed until the turn of the First and Second Millennium. Then, as a result of the Roman bishops’ struggle for emancipation from secular rulers as well as the dispute over investiture, Pilate, in the perception of the Church, became what he was: a cynic who had lost his taste for truth.

In the twenty-first century the gospel image of Pontius Pilate has proved remarkably enduring. Today, in Pilate and his gesture of the Washing of hands – the harbinger of the changes now being introduced everywhere in the West – we see the image of the modern democratic ruler. He deliberately retreats into the shadows, “handing over” decision-making power to the people. In this way, but only temporarily, the eternal Pilate once again manages to absolve himself of his responsibility before the History.

The rejection of the conviction that Christianity was not meant to Christianise, but to overcome the Empire (something of which the pagan Roman authorities quite rightly and shrewdly accused the first Christians!) over the centuries has led to the quasi-dogmatic conviction that there can be only one Empire. Just as there is one God, one Redeemer, one Church and one Scripture. In this sense the “official creed of the Empire” was then becoming one of the key definitions of Orthodoxy.

“Wherever the power of thought may wander, whether to the East, or to the West, on earth, or to Heaven itself, everywhere it sees the Blessed Caesar, inseparable from his kingdom. His children reign over the earth. Like new luminaries, they illuminate the earth with the light of their father. He lives in them by his own power, increasing it in their succession, and governing all the universe even more perfectly than before”, – we read in Eusebius of Caesarea (263–339) in his Praise of Constantine. Faith in One Empire necessarily led to the denial of the authenticity and orthodoxy of the states and churches which were outside of it. It turns out that, with the division of the Empire, the Separation of the Churches into Orthodox and Catholic Churches was bound to happen inevitably.