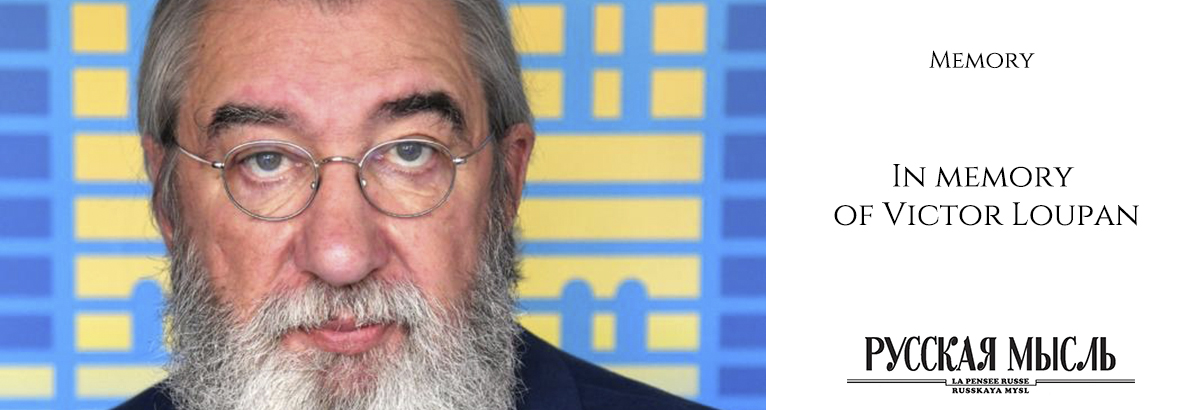

Pages of life journey of an outstanding journalist

Mikhail Lepekhin, literary historian

I met Victor Nikolaevich Loupan in the summer of 1995 at his old friend (connected since their adolescence), the chairman of the Russian Bibliographical Society, Anatoly Pavlovich Petrik.

The beginning of friendship between Loupan and Petrik should be attributed to the 1960s, when both studied at the School No. 1 in Chisinau. The acquaintance was both at school and home: their fathers belonged to the highest stratum of the republican nomenklatura. In those years Pavel Petrovich Petrik (1925–2014) headed the trade unions of the Moldavian SSR, Nikolai Ivanovich Loupan (1921–2017) was the editor-in-chief of the Moldavian television, which largely owed to him, if not for the fact of establishing, then for its successful work over the first fifteen years.

The long life of Nikolai Ivanovich was quite difficult. Several generations of ancestors were peasants of the village of Chepeleutsi, Khotinsky district, Bessarabian province (now the Edinet region of Moldova). In the year of Nikolai Ivanovich’s birth, the village belonged to Romania. Born as the 10th child, since his early childhood he had been striving to achieve something more than the monotonous rural life, and through tireless work, he slowly achieved each of his goals. Having received a primary education, for which he had to go daily to a neighboring village, he graduated from a school for junior officers. A career as a military professional was not his goal, but he could not have achieved more in 1940. In the rank of senior sergeant of the Romanian army, he fought first against the USSR, but since 1944 against the Third Reich. After demobilisation, Nikolai Ivanovich returned to Chepeleutsy, where in 1945–1952 he taught mathematics at a local school. (In 1940, Bessarabia became part of the USSR, which did not have the best effect on the relatives of Nikolai Ivanovich: in the spring of 1941 they were dispossessed and deported to Siberia as special settlers). In 1952, he was invited to Chernivtsi, the capital of Bukovina (since the end of the 19th century, the city has enjoyed the fame of “little Vienna”). It was there that on April 3, 1954, the baby Victor was born. In 1958, the family moved to Chisinau, where Nikolai Ivanovich took a leading position at the State Radio and Television of the MSSR.

The long life of Nikolai Ivanovich was quite difficult. Several generations of ancestors were peasants of the village of Chepeleutsi, Khotinsky district, Bessarabian province (now the Edinet region of Moldova). In the year of Nikolai Ivanovich’s birth, the village belonged to Romania. Born as the 10th child, since his early childhood he had been striving to achieve something more than the monotonous rural life, and through tireless work, he slowly achieved each of his goals. Having received a primary education, for which he had to go daily to a neighboring village, he graduated from a school for junior officers. A career as a military professional was not his goal, but he could not have achieved more in 1940. In the rank of senior sergeant of the Romanian army, he fought first against the USSR, but since 1944 against the Third Reich. After demobilisation, Nikolai Ivanovich returned to Chepeleutsy, where in 1945–1952 he taught mathematics at a local school. (In 1940, Bessarabia became part of the USSR, which did not have the best effect on the relatives of Nikolai Ivanovich: in the spring of 1941 they were dispossessed and deported to Siberia as special settlers). In 1952, he was invited to Chernivtsi, the capital of Bukovina (since the end of the 19th century, the city has enjoyed the fame of “little Vienna”). It was there that on April 3, 1954, the baby Victor was born. In 1958, the family moved to Chisinau, where Nikolai Ivanovich took a leading position at the State Radio and Television of the MSSR.

Well-known Moldovan film directors, journalists, actors, writers, artists were frequent visitors to the hospitable house of N. I. Loupan, and Victor grew up in a creative environment. The best school in Moldova, where he studied, granted him an in-depth knowledge of the French language, which early became his third native language (along with Moldovan and Russian).

Thanks to the high administrative status of Nikolai Ivanovich in the 1960s, about ten of his relatives deported to Siberia were given the opportunity to return to their native Chepeleutsy.

In the 1970s, the paths of Anatoly and Victor diverged for almost a decade and a half. Both entered the faculties of philology: Anatoly – to the Swahili Division of the Department of African studies of the Institute of Asian and African countries at Moscow State University, Victor chose the French Division of the University of Chisinau.

For Victor, a quiet life ended, when in 1970 his father was removed from his post for “a gross political mistake – promoting Romanian bourgeois nationalism” (relations between the USSR and Romania were damaged in 1968, when Romania condemned the entry of the Warsaw Pact armies into Czechoslovakia). In Moldavia, the suspicion of Romanianism began to be regarded as one of the most serious ideological sins.

Was there such a thing? Hardly: N. I. Loupan was not a political self-murderer, however his position was the object of desire of his colleagues. The former subject of the Romanian Kingdom with a difficult fate, already due to his background, was very vulnerable to cultivation in the course of the career manipulation of the central and regional administrations. (NB! Provocations of the 1970s carried out among the Moldavian intelligentsia were demonstrated in “Aquarium” by V. Suvorov). The intrigue succeeded with the desired result: Nikolai Ivanovich was left without work with a strict party reprimand. For an ideological worker, the wording of dismissal and reprimand were equated with a ban on the profession. According to the unwritten rules of the nomenklatura, the failed one had to be offered a position of equal value or with a slight decrease – but there was no such position in the Moldavian SSR… After spending more than two years unemployed, the father of three decided on an extraordinary act for persons of his status: he applied to emigrate from the USSR together with the whole family. After the signing of the Final Act of the so-called “Helsinki Accords” by the “freest country in the world” in 1973 – the agreements which granted citizens the right to freely choose their country of residence, Nikolai Ivanovich theoretically acquired such a right, but it was hardly exercisable.

Acquaintance with P. P. Petrik helped. Since the late 1940s, Petrik enjoyed the patronage of the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Moldavian SSR Leonid Brezhnev. Being familiar with Nikolai Ivanovich for quite a long time and knowing full well that he could not survive with the label of a “dissident” in Moldova, Petrik vouched for him before Brezhnev, and in 1974 Nikolai Ivanovich left for Paris for permanent residence with his wife and three children (permission to do so belonged to the competence of the head of the Department of Administrative Bodies of the Central Committee of the CPSU N. I. Savinkin, who could not issue it without the knowledge of the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU). During Soviet times, the departure of a nomenklatura official of such a high rank was an exceptional case, which is why later the personality of Nikolai Ivanovich was overgrown with many conspiracy speculations – given the position that he took in the Bessarabia and Bukovina fellowcountrymen’s association headed by him and in the world Romanian Diaspora from the beginning of the 1980s.

In the meantime, a father and a son had to re-learn. Having moved from Paris to Brussels, they entered local universities. At the age of 57, Nikolai Ivanovich graduated from the Free University of Brussels, after which he obtained the right to engage in journalism professionally. And Victor, having entered the Brussels Institute for Theater, Cinema and Sound, specialised in directing. With a scholarship from the Belgian Ministry of Culture, he created a theatrical enterprise, staging three performances based on his own plays in two years; the success was noted by the Belgian mass media.

Victor completed his education in Los Angeles at the American Film Institute’s Film Directing School, but he decided leave Hollywood, as he accepted an offer from the University of Louisiana to teach directing. In Baton Rouge, Victor taught from 1982 to 1984, but then did not renew the contract, because he felt a vocation for creativity, and not for professorship.

Victor completed his education in Los Angeles at the American Film Institute’s Film Directing School, but he decided leave Hollywood, as he accepted an offer from the University of Louisiana to teach directing. In Baton Rouge, Victor taught from 1982 to 1984, but then did not renew the contract, because he felt a vocation for creativity, and not for professorship.

In 1985, Victor returned from the banks of the Mississippi to the banks of the Seine, where his relatives settled. By that time, his father had already become a full-time employee of Radio Free Europe, and also headed the Bessarabia and Bukovina fellowcountrymen’s association, which existed in 24 countries and numbered over a hundred thousand participants. Nikolai Ivanovich had a reputation as one of the world’s greatest experts on the real history of Romania in the 20th century, was the author of a number of books and articles, and the organiser of many scientific conferences and seminars. As for Victor, he returned to teaching in 2014, teaching courses in film analysis and film language at the Institut Georges Méliès in Paris.

The so-called “Romanian issue” was alien to Victor himself – to the same extent as the Soviet problems were far away from him. He refrained from contacts with emigre circles, perfectly understanding the dead-end nature of the subsequent development of events. Almost immediately, a well-trained young documentary filmmaker attracted the attention of the intellectual world of France. In the second half of the 1980s, Loupan made four full-length documentaries. The most famous of them in 1987 was a film dedicated to the fate of Soviet prisoners of war in Afghanistan, it received a prize as the best humanitarian film of the year. Victor helped M. M. Shemyakin in their rescue from the captivity, whom he met in the United States and with whom he was connected through a long-lasting friendship. The film became a world-class event: after it, the USSR began to show interest in the fate of the prisoners of war, who were routinely written off as irretrievable losses. Of course, the film was not shown in the USSR: the topic of death in the Afghan war was tabooed until the early 1990s.

In 1986, Victor met Louis Povel (1920-1997): the legend of French journalism was interested in Loupan, and after a detailed conversation with him, Povel blessed the 32-year-old filmmaker on the thorny path of documentary reporting in the press.

In 1987, Victor was invited to the weekly Le Figaro Magazine: the author specialised in interviews (over 200 of them were prepared) and military reports. Chief editor Henri-Christian Giraud gave Loupan complete freedom in choosing topics. Among the interviewees were A. Tarkovsky, I. Brodsky, S. Hussein, A. Pinochet, J. Arafat, E. Honecker, G. Aliyev, E. Shevardnadze, M. Gorbachev, S. Niyazov, D. Dudayev, A. Lebed, as well as persons whose fame was created by Victor himself. He repeatedly appeared on French television; they began to recognise him in the streets and start a conversation with him (he gained fame and acquaintances instantly).

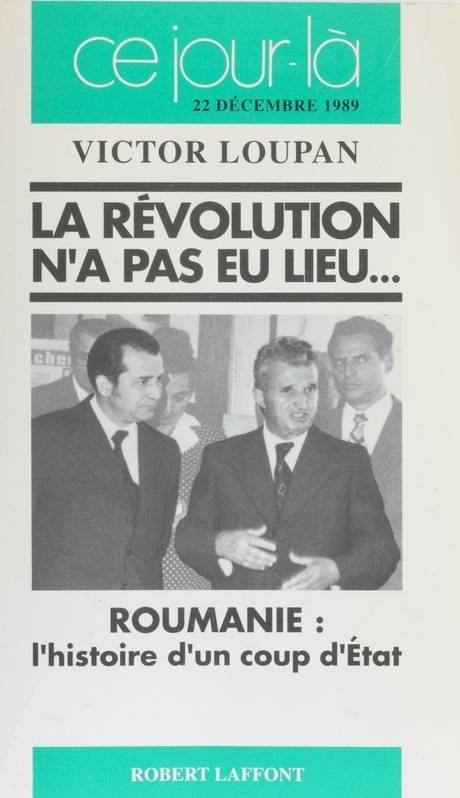

As a result of a long trip to Romania after the “velvet revolution” that followed the execution of the Ceausescu spouses, Loupan’s first book, La Révolution n’a pas eu lieu: Roumanie, l’histoire d’un coup d’Etat (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1990) was published. In it, he convincingly proved that there was no revolution, but there was a coup d’état planned with sufficient care. The future of Romania, headed by I. Iliescu, seemed extremely unenviable to Loupan – even in comparison with the dictatorship of the overthrown “genius of the Carpathians” cursed at that time by everyone. The further development of events in Romania and the comprehension of what had happened showed the complete correctness of Loupan’s conclusions about the recent past and his forecasts for the near future.

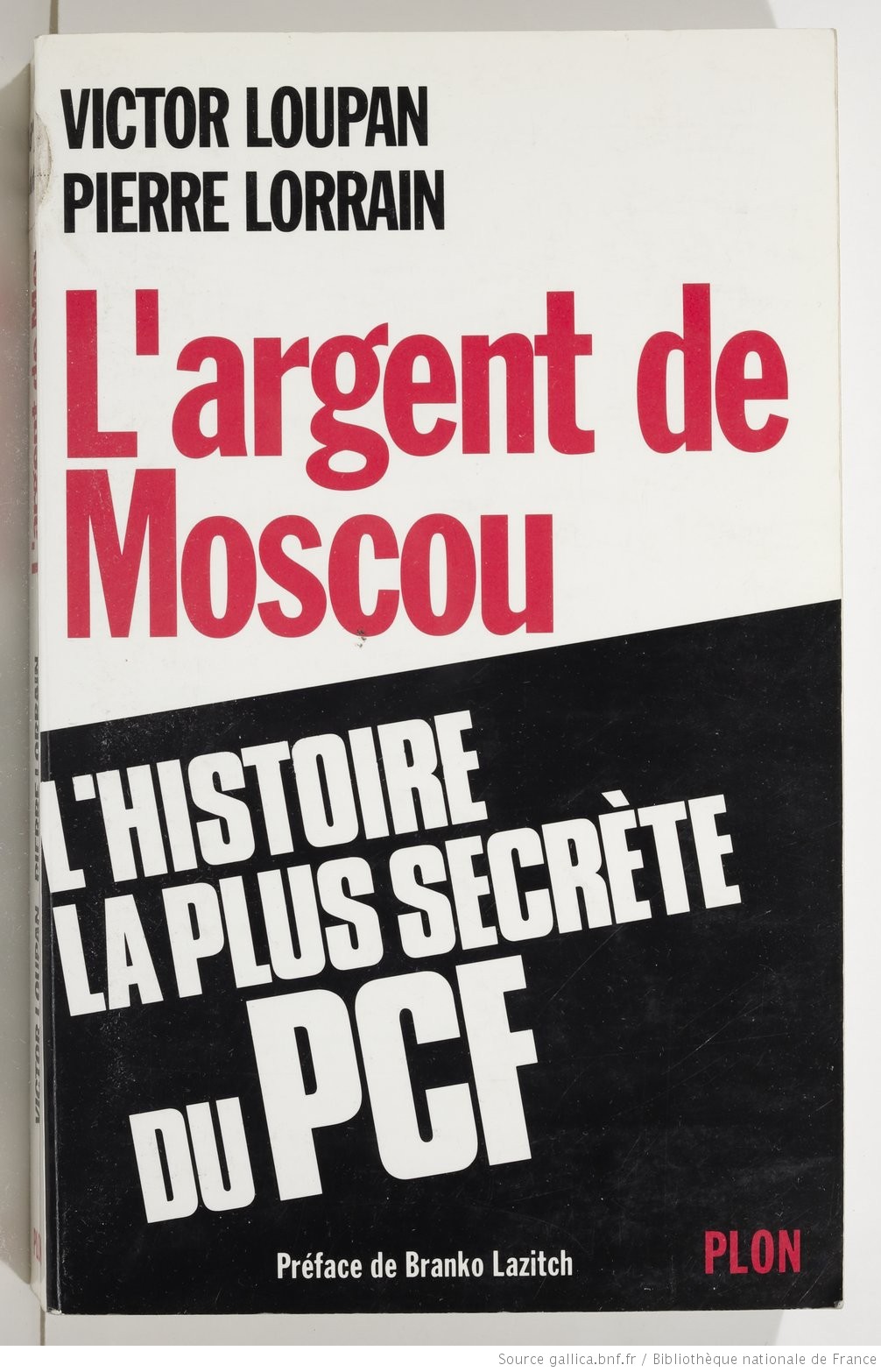

In July 1989, after 15 years of separation, a meeting of old friends took place: A. P. Petrik arrived in Paris for a session of IFLA (The International Federation of Library Associations). In the autumn, Victor visited Moscow, and later trips became quite frequent. Since 1992, Loupan began to work on a book about the Comintern. By that time, the archive preserved in the former Institute of Marxism-Leninism of the Central Committee of the CPSU (now the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History), became available to researchers. The subject of Loupan’s main investigations was not the subversive activity of the revolutionary octopus, which entangled the whole world with tentacles, but the well-established mechanism for financing the so-called “national liberation movements” by the Comintern using the example of the French Communist Party. The result was the book L’Argent de Moscou: L’histoire la plus secrète du PCF (Paris: Plon, 1994), which, unfortunately, has not yet been translated into Russian. At that time, one of the first studies on the Comintern based on primary sources could not fail to attract the attention of historians and Sovietologists. The book has not lost its significance even today due to the abundance of documents cited in it.

Loupan’s authority as a serious researcher and his moral qualities in 1994 became the reason for his inclusion in the press pool, which accompanied A. I. Solzhenitsyn for two months on his triumphant return to Russia after two decades of exile. The status of Loupan is evidenced by the fact that he was traveling in the same carriage with the writer – from the journalists there was only a BBC production team led by Archie Baron, who was granted the exclusive right to televise the trip of the Great Writer of the Russian Land in Russia – the rest could only photograph and make records.

Loupan’s authority as a serious researcher and his moral qualities in 1994 became the reason for his inclusion in the press pool, which accompanied A. I. Solzhenitsyn for two months on his triumphant return to Russia after two decades of exile. The status of Loupan is evidenced by the fact that he was traveling in the same carriage with the writer – from the journalists there was only a BBC production team led by Archie Baron, who was granted the exclusive right to televise the trip of the Great Writer of the Russian Land in Russia – the rest could only photograph and make records.

Solzhenitsyn was greatly revered by Loupan as a man who, by his own strength, had risen to an unattainable height. To no lesser extent, he revered N. D. Solzhenitsyn as an ideal wife, especially emphasising her organisational talents. According to Loupan, the recognition of family values as dominant brought them closer: both had three children.

As I have already indicated, in July 1995 I met Victor. We quickly warmed to each other. Loupan behaved easily, without the slightest snobbery, and talked a lot and fascinatingly about his trips around the globe. I was pleasantly surprised by the objectivity of assessments, the complete absence of any negative opinions about certain persons, healthy optimism in the forecast for the near future. He told a lot, and exactly what was not included in the records (I regret that I did not write down the story about the pursuit of Brodsky in the USA and Europe from memory, but with the help of Veronika Shilts, a many-hour interview was finally received). We exchanged phone numbers, and as soon as I traveled to Paris, I paid a short visit to Victor (to the editorial office). He happily met me and after dinner drove me to my temporary residence on a motorcycle. He chose a motorcycle taking into account his own large complexion – it seemed to me that I was riding a Percheron. High-speed raid through Paris among trucks and buses is still memorable.

In the autumn of 1997 Victor paid me a return visit. He was led to Saint Petersburg by Giraud’s interest in the problem of “royal remnants”. The secret burial of the executed royal family found in 1979 by the Ural geologist A. N. Avdonin, in the 1990s became a stumbling block in the relationship between monarchists, the Russian Orthodox Church, secular authorities at different levels, historians, and publicists. On the eve of the 80th anniversary of the death of the Royal Family, the dispute about the authenticity of the remnants renewed. Loupan, who stayed with Avdonin for a week in Yekaterinburg, initially agreed with his conclusions after reading all the documentation provided to him. On the trip, Victor was accompanied by his namesake, the outstanding photo artist Victor Petrovich Gritsyuk (1949‑2009), who was in charge of the photo department of the magazine “Rodina” and a person of remarkable spiritual qualities.

I met two Victors at the airport – and we went from Pulkovo straight to my place. Having laid down the equipment, Gritsyuk expressed a desire to visit the Smolensk cemetery and bow to St. Xenia. We set off, arrived in the middle of the service. After approaching the cross, Archpriest Fr. Igor Esipov turned to me with a question about the guests – two men of heroic stature. I introduced them to each other, a conversation ensued… Loupan asked a question about the royal remnants – in response, Fr. Igor brought out the issue of The Journal of the Moscow Patriarchy with the appropriate explanations, ordering it to be returned after reading. They went to me. “I have already read it. Can another authoritative priest or maybe even a bishop answer all my questions?”, he asked me.

I immediately forwarded Victor’s question to the spiritual writer A. N. Strizhev, calling Moscow and recommending Loupan in the most flattering way. Alexander Nikolaevich immediately called the famous archaeologist L. A. Belyaev, who called Alexy II; and so, consent for the interview was obtained. Half an hour later I answered Victor’s question: “Will the patriarch suit you?”

The next morning, Loupan visited a well-known building in Chisty Pereulok, where he was provided with the same article from the JMP and offered to formulate questions for a written interview based on it. The text of the interview was agreed upon within three days. Published in Le Figaro Magazine, it immediately became a world-class sensation: before that, the patriarch had not given interviews to foreign journalists, especially on such a sensitive topic. As you know, the ROC (MP) at that time categorically rejected the authenticity of the “Yekaterinburg remnants”, making it impossible to venerate them as holy relics. At present, their authenticity is not in doubt; in May 2022, they are supposed to be recognised as such at the Bishops’ Council.

An interview with Patriarch Alexy II contributed to Loupan’s career in both secular and spiritual manifestations. Probably, then he met the chairman of the Department for External Church Relations, Metropolitan Kirill (Gundyaev), now the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia. Since the early 2000s, their meetings in Moscow and Paris have become systematic. Knowing everyone and everything in Paris, Victor was helpful to Bishop Kirill both with his connections and a balanced assessment of the mood in the church environment. It is natural that, with the blessing of Bishop, Loupan became one of the leaders of the Movement for a local orthodoxy of Russian Tradition in Western Europe created in 2004, which he left in 2006 indicating the following reason: “due to disagreements with the board members”. Such a delicate wording reflected Loupan’s sharp confrontation with his fellow members. The latter could not determine the canonical status of “a local orthodoxy of Russian Tradition in Western Europe”, as well as indicate the sources of its financing – in projecting they represented it as something like a local Church, but as such, of course, it could not count on the recognition of other Churches.

Loupan, who took a realistic view of things, persuaded the fellow members in favour of “returning to fold of the Mother Church,” but the fellow members did not perceive the Moscow Patriarchate as such. 13 years later, the idea, which seemed stillborn, was crowned with success in 2019: the Archdiocese of Russian Orthodox churches in Western Europe was created by voting and accepted into the Moscow Patriarchate. An important role in this event is associated with the name of Loupan, who tirelessly crushed the enemies of the Moscow Patriarchate with the power of his journalistic gift.

For services to the Moscow Patriarchate, Loupan was introduced to the Patriarchal Council for Culture (2010). Victor considered as a matter of special importance and honor to take part in the annual meetings of the Council headed by Metropolitan Tikhon (Shevkunov), and invariably visited Moscow.

In the autumn of 2019, Loupan was invited by Patriarch Kirill to Moscow for the celebration of the entry of the entirety of the Archdiocese of Russian Orthodox churches in Western Europe into the Moscow Patriarchate. In summing up the results of the vote, his merit was great as an assistant to the church warden of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral.

Loupan played a significant role in the creation of the Archdiocese – conceived back in 2003 by Patriarch Alexy II as the metropolitan district holding a special status as a part of the Moscow Patriarchate, consisting of parishes under the jurisdiction of the Constantinople and Moscow Patriarchates, as well as the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR), now, in 2022, the Archdiocese fully corresponds to the original plan of His Holiness.

Loupan saw no less service to the Church in his participation in the fate of the reader of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral Seryozha Tutunov (born 1978), the nephew of the artist S. A. Tutunov, his old Parisian friend. A deeply religious young man, a talented mathematician graduated with honors from the Moscow Theological Academy and Seminary, transferred to the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate, and in 2006 was admitted by Metropolitan Kirill to the staff of the Department for External Church Relations. Now Bishop Savva (Tutunov) of Zelenograd, vicar of the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, is the deputy director for temporal affairs of the Moscow Patriarchate, the head of the audit and analysis service of the Administrative Department, and also a permanent member of the Inter-Council Presence, de facto being one of the five most influential persons of the Moscow Patriarchate.

How religious was Victor? It is my understanding that he developed an in-depth interest in the Church after the interview with the Patriarch, and the abbot of the Sretensky Monastery, Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov) (Metropolitan of Pskov and Porkhov since 2018), played a decisive role in his development as a deeply religious person. The personality of Bishop Tikhon is well known, there is no need to tell even more. Two graduates of the stage management faculties – one of the Moscow State Institute of Culture and another of the American Film Institute – found each other. Both are distinguished by a total lack of exaltation and attraction to mysticism, as well as a combination of piety and sanity. Speaking of Bishop Tikhon, Victor invariably added: “The future belongs to him”.

But let’s go back to the last millennium.

In September 1999, I worked in the Moscow archives. At that time, residential buildings were blown up in Moscow, Buynaksk and Volgodonsk, and FSB officers were detained in Ryazan while planting explosives in the basement of a high-rise building. (I will not comment on this story: just type in the search engine: “Conspiracy theories about explosions of residential buildings (1999)” and “Ryazan sugar”.)

On September 20, Petrik told me that Loupan had arrived and really wanted to meet me. I immediately called, and Victor offered to dine tomorrow at the Marco Polo Hotel (which is on Spiridonovka), where he was staying. On Tuesday, September 21, a conversation took place at the meal, the course of which I remembered almost verbatim. Loupan said that he would stay for a week to write an article about the explosions of residential buildings and would very much like to know my opinion on this (probably he had the opinion that I was competent enough in all the innermost secrets of Russian history). I had to disappoint Loupan, because I could not add anything new on this story, since I learned about what had happened from the media, and even then I paid not much attention to the topic. On the proposal to prepare the text of the article on this topic in a short time, I immediately refused, because it seems to me unnatural to express someone’s opinions and retell other people’s texts. I was pleasantly flattered by my importance, but I did not want to plunge into the dull Russian conspiracy theories. I tried to explain that I consider the external world mainly from the bibliographic point of view, and the present in general interests me very little. Moreover, who exactly blew up the houses, the Russian secret services or the Caucasian terrorists, is simply not interesting to me, since this is not part of my research interests.

Victor did not expect such a sharp refusal and after a pause he asked me: is there a decent and competent person among my acquaintances, who, for a decent fee, could prepare such an article on condition of anonymity or (if the name of the author is sufficiently known) while not hiding? To that I replied that the former secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation with special powers, the governor of the Krasnoyarsk Krai, Lieutenant General A. I. Lebed, an old friend of Loupan, fully corresponds to the criterion of decency and competence. After that Victor looked at me for a long time and did not say anything – and so, we parted and did not see each other again during that visit. I know about everything that followed the conversation only from the words of A. P. Petrik, who always had a special interest in Moldovan events (his father headed Tiraspol for many years, and as secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the MSSR supervised Transnistria) and was personally acquainted with Lebed (NB! His special powers resulted in signing of the Khasavyurt agreements on August 31, 1996, for which Lebed is still cursed by Russia!).

As Petrik told me a month later, after arranging a meeting with Lebed, Loupan flew to Krasnoyarsk on Thursday. The governor dedicated the entire Friday to his old friend: they traveled around the neighborhood, took a steam bath, had a hearty dinner – and all this time they talked, since they had not seen each other for several years… In the evening, the conversation turned into a recorded interview: with the consent of the interlocutor, Loupan turned on the recorder. Lebed answered all his questions with the utmost frankness, with his characteristic clarity of wording and without mincing words; there could be no ambiguous interpretation of what he said. On Saturday, Victor flew to Moscow, on Sunday – to Paris. From all that Lebed said, a coherent text was compiled in the form of an interview; all words that were inconvenient in print were also removed.

And then there was a crack of thunder!

It happened on the morning of Wednesday, September 29, 1999, when the latest issue of Le Figaro was published and Lebed said: “I am almost convinced that the explosions in Moscow were organised in the Kremlin. The goal is to disrupt the upcoming elections in any way in order to keep the exhausted and discredited Yeltsin clan in power”. According to Lebed, “houses were blown up not by Chechens, but by bandits and mercenaries who have no nationality – and they did it based on the orders of power structures in Moscow”.

Even despite the fact that most of the interview was devoted personally to General Lebed and his vision of what was happening in Russia, and that he did not seek to convince everyone of the correctness of his version, but only told about what was obvious to him, all attention was focused precisely on a fragment about explosions. Immediately the press secretary of the President of the Russian Federation D. E. Yakushkin called the interview “a malicious provocation on the part of the general” and a “delusional version”. Then Prime Minister V. V. Putin reacted just as instantly, declaring at a press conference in Cheboksary that he “treated the general very well” and called the ill-fated interview “complete nonsense”: “I do not believe he said that”. Putin also rejected the version itself: “It is absolutely impossible. Making a political career on blood is unacceptable”.

On Thursday, September 30, 1999, a photo of a frowning Lebed appeared on the front page of Izvestia, A. Maskhadov stood as an ominous shadow behind him. The (anonymous) editorial was headlined: “COUP / Alexander Lebed accuses the authorities of organising terrorist attacks. The general is preparing to enter the Kremlin on a white horse / Honor for export”. The article in Le Figaro (its text, of course, was not cited) was reported in the retelling of the Paris staff correspondent of Izvestia E. Guseynov. According to the anonymous source, among the “most sensational of the many shocking statements made by the Krasnoyarsk governor in an interview with Le Figaro newspaper, Lebed announced that he was ready to immediately head the new Russian government on one condition: Yeltsin must immediately leave the Kremlin”. According to the Izvestia’s anonymous source, “only two options for the development of his relationship with B. A. Berezovsky could have prompted Lebed to make such a harsh statement”. The first option: “The impudence of Lebed’s actions in relation to the existing government and his declaration of war against the Kremlin are explained by the fact that Lebed quarreled with Berezovsky”. Option two: “Berezovsky has completely quarreled with the Kremlin and is using Lebed as a battering ram”. The final conclusion of Izvestia was made in the best traditions of Soviet agitprop: “The general, who gave an interview to foreign “voices”, choking in his own ambitions, showed disrespect for his country, his people and he beats in the very heart of Russia”.

On the same day, that is, the day after the publication of the interview, the press service of the governor of the Krasnoyarsk Krai issued a statement “about Alexander Lebed’s interview to Le Figaro newspaper, which caused some noise”. The statement said: “Alexander Lebed, having read the comments on his interview to Le Figaro newspaper, ordered to provide him with a full translation of the text published in Le Figaro”. “After reading it, Lebed said that he fully realised again that quotes leave much more room for fantasy than the text from which they are taken”. In addition, “Lebed complained that he had forgotten how to explain simple things to foreign journalists”. Almost on the same day, Berezovsky flew to Lebed, after which the Governor-General no longer talked about explosions or gave interviews, and the interview itself suddenly ceased to be mentioned in mass media, as if it did not exist at all. (Especially since D. S. Likhachev died on September 30 and mass media got other breaking news).

In the future, I never spoke about it during conversations with Loupan. As Petrik told me, the consequences of the interview (or rather, the collapse of Lebed’s political career) were painful for Victor (he considered the general to be his personal friend), but he could not overcome the temptation of a journalistic sensation. I regret that I did not see the original text in Le Figaro, I did not show timely interest in this story. Nevertheless, almost immediately a rumor spread that Yeltsin, who had previously invariably favoured Lebed and saw him among possible successors, was so furious that he vented his anger at his subordinates, who admitted the very possibility of such an interview.

As for Lebed, after Yeltsin’s anger, he should have forgotten about presidential ambitions. Due to the unpredictability of his behavior (he betrayed everyone who had the stupidity to deal with him) and his complete inability to manage the region (that he proved in the Krasnoyarsk Krai), Berezovsky, who led him de facto, backed down. When Putin ascended to the presidency of the Russian Federation, the Krasnoyarsk governor finally turned into a political marginal. His death in a helicopter crash could not surprise those who knew him. So, according to A. P. Petrik, Loupan categorically rejected the version of the premeditated murder, who repeatedly flew with Lebed in a helicopter. According to Victor, the general liked to personally stand behind the pilot and direct the flight. The fact that a helicopter without a map got caught on a power line wire should be considered a tragic coincidence: sabotage is not done that way.

Loupan experienced hard the death of the general, whom he knew well from Transnistria, – I know about this again from the words of Petrik, because I never spoke with Victor about Lebed again.

It is worth noting that our conversations were more devoted to the past than to the present.

Loupan was interested in one of the topics of my research – the biography of the author of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” M. V. Golovinsky (1865–1920). When Victor told Giraud about this, he offered to write an article on this subject in the form of an interview with me. Having discussed the conditions, I agreed, and Loupan, together with Gritsyuk, flew to Saint Petersburg.

Previously, the text of the article was already prepared by me, and the interview was carried out for four hours. Victor asked the questions about what, in his opinion, needed to be specifically explained to French readers. In August 1999, the article was published. That same morning, Loupan received a phone call from J.-F. Revel, thanking him for the pleasure to read the text written in a highly professional manner. Then, in the course of the conversation, it became clear that the ruler of the minds of the French intellectuals tried not to miss a single piece created by Victor – such recognition later became a source of special pride for Loupan.

This story had a sequel. The article attracted the attention of another ruler of the minds of European intellectuals – P.A. Tagiyev, who still has a global reputation as the largest specialist in the “Protocols”. He was carried away by the article, where, among others, I disavowed a number of traditional liberal myths, suggesting that my friend, publicist E. Conan, prepare a paired interview (mine and his). Eric was received by me in Saint Petersburg; during a nine-hour (with a lunch break) detailed interview, a number of puzzling circumstances were clarified – and his article appeared in L’Express at the end of November 1999 – just in time for the 100th anniversary of the “Protocols”.

When I arrived in Paris in March 2000, Victor informed me that Giraud wanted to meet me and that it was only a quarter-hour courtesy visit. At 6 PM I went up to the office of the editor-in-chief of Le Figaro Magazine and introduced myself. Thanking for the cooperation with the magazine, Henri-Christian mentioned his grandfather, General of the Army Giraud. It just clicked in my mind, and I automatically asked: “So you are a baby in a pushchair?” The interlocutor with amazement confirmed my assumption, after which the conversation took on a relaxed character.

To comprehend the dialogue, a small comment should be made. The celebrated hero of the First and Second World Wars Henri Honoré Giraud (1879–1949) is still one of the most significant figures for the French traditionalists. The only one of all the French military leaders, he resisted to the last the superior troops of the Third Reich. After being captured, he was imprisoned in the Königstein Fortress (near Dresden), from where he escaped, at the age of 63 descending a rope from a castle window into a gorge, and then walked about 800 km on foot to the Swiss border. Almost immediately, General Giraud turned into a national hero – a symbol of unconquered France; the popularity of Charles de Gaulle was very insignificant in comparison with him. Giraud’s extreme anti-communism and his skillful political maneuvering between traditional values and democracy made him suspicious in the eyes of Stalin, who opted for de Gaulle because of his demonstrative anti-Americanism and pro-Soviet orientation. Both leaders became co-chairmen of the French Committee of National Liberation on June 3, 1943, and only on the fifth attempt was it possible to photograph them shaking hands in the presence of Roosevelt and Churchill – they both pulled them back so quickly with disgust. On August 4, 1943, Giraud became the commander-in-chief of the CFLN troops, but left both posts through de Gaulle’s intrigues.

Despite the formal loss of his posts, the moral authority of the elderly Giraud was unusually high, and he posed a real threat to de Gaulle’s autocracy, remaining vice-chairman of the Supreme Military Council.

Living at the Villa Mazagran (Oran), Giraud used to take a walk with his wife at the same hour – his grandson was in a pushchair at that time. On August 23, 1944, an assassination attempt was made on General Giraud – a Moroccan shooter rushed at him with a knife. The grandmother covered her grandson with her body, and Giraud, with the help of a guard, neutralised the attacker. He was almost immediately sentenced to death by a tribunal subordinate to De Gaullists and executed. Despite the obvious involvement of de Gaulle’s secret service in the assassination attempt, this has not been proven.

The baby grew up and eventually became the editor-in-chief of Le Figaro Magazine.

After clarifying all the circumstances, a quarter-hour visit turned into a three-hour conversation. Henri-Christian Giraud has accumulated several questions relating to the history of Russia, to which I have tried to answer conscientiously. I was very sorry that Loupan did not take part in the conversation: far from always my French was sufficient for a detailed answer. All this time Victor was waiting for me in his office and after the conversation ended, he took me to the nearest Berber Cafe for dinner (it was the headquarters of Le Figaro Magazine, where its employees spent most of their office time). At the end of the meal, Victor took me on a motorcycle to my temporary residence in Auteuil. Such a strange way of driving around Paris no longer surprised me, but Loupan was impressed by a story about the apartment where I rented a room. This apartment (33, rue Erlanger) at the end of 1944 was received as a trophy by one of the most seasoned French communists (she was still alive at the end of the 20th century) – as “the escheated property of a German collaborator”. That turned out to be… P. B. Struve, who died in my room on February 26, 1944 (as N. A. Struve clarified this to me, who visited his grandfather several times upon his return from Belgrade). Another ending to the story…

To be continued…