Switzerland has been playing an outstanding role in world politics, culture and even in structuring of the world order for many centuries

VICTOR LOUPAN, Head of the Editorial Board.

In the modern mind, Switzerland is a small, prosperous country known for its expensive watches and fashionable ski resorts. In fact, the Swiss state has been playing an outstanding role in world politics, culture and even in structuring of the world order for many centuries in a row.

Swiss, let’s say, neutrality allowed this small and sparsely populated mountainous country to separate itself from the tragic essence of European history and position itself as a harbour of refuge where sworn enemies can safely moor, while brutally fighting each other literally beyond its borders. This state of affairs was especially manifested during the Second World War, when neutral Switzerland was almost the only place in the world where the warring parties could appear at the same time and even hold tacit negotiations and conduct “business”. The conduct of this “business” was determinatively facilitated by the unique Swiss banking system with its absolute secrecy, encrypted bank accounts with their anonymous holders and other anomalous rules, absolutely prohibited in the rule of law and democratic countries.

We should not forget that Switzerland is not just a democratic state, but a kind of model of democracy, where the direct declaration of the will of the people is more important in its essence than the so-called representative democracy in all the European states surrounding Switzerland. The referendum in Switzerland is not an exception, but rather the norm. Moreover, the Swiss hold it almost every year, and sometimes even more often, on a variety of topics – from constitutional to migration matters.

Switzerland is considered a prosperous but boring country where nothing ever happens. But is it?

In the south Switzerland, which is dominated by the Alps, is bordered by Italy, in the west by France, in the north by Germany, and in the east by Austria and Liechtenstein. The population of the country (approximately 8.5 million people) is mainly concentrated on the plateau, where the largest cities are located, including two global polises – Zurich and Geneva. In Zurich, mostly German is spoken, and in Geneva, French. There is also a small part of Switzerland where the Italian language dominates.

This multilingualism is explained by the fact that the country is located at the crossroads of Germanic and Roman civilisations. The majority of the population is German-speaking, but the Swiss national identity is rooted to a common historical experience, common values, which are federalism and direct democracy, Alpine symbols. Because of its multilingualism, Switzerland is known by many different names, however Swiss coins and postage stamps use the Latin name of the country instead of national languages: Confoederatio Helvetica, usually shortened to simply Helvetia.

Multilingual countries usually do not have their own culture. Swiss culture is no exception. It developed, on the one hand, under the influence of German, French and Italian cultures, and on the other hand, on the basis of the special identity of each canton. And therefore it is difficult to say exactly what “Swiss culture” actually is. In Switzerland itself, there is a distinction between “Swiss culture” (usually folklore) and “culture from Switzerland” which includes all available genres in which people holding a Swiss passport work.

Switzerland gave German culture, for example, the brilliant Friedrich Dürrenmatt, who was nominated seven times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Or Carl Gustav Jung – a psychiatrist, teacher and thinker, the founder of one of the areas of depth psychology and a close associate of Sigmund Freud.

In French culture, the Swiss played perhaps an even more significant role. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, without whom French and European education is inconceivable, was a Swiss. It is not for nothing that he is called the forerunner of the French Revolution, for Rousseau, for the first time in political philosophy, tried to explain the causes of social inequality. He argued that the state arises as a result of a social contract, which means that supreme power belongs to the whole people. “Popular sovereignty is inalienable, indivisible, infallible, absolute,” he argued. Under the influence of Rousseau’s ideas, such new democratic institutions emerged as a referendum, a popular legislative initiative, a reduction in the term of deputy powers, a mandatory mandate, and the recall of deputies by voters.

The famous Madame de Staël was also a contemporary of Rousseau. As a writer, literary theorist, publicist, she had a great influence on the literary tastes of Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. Being a daughter of the French Finance Minister, the Swiss millionaire Jacques Necker, she enjoyed authority in political circles and publicly opposed Napoleon, for which she was expelled from France. She defended gender equality and promoted romanticism in art.

In 1812, Madame de Staël, an authoritative historian of the French Revolution and an exile pursued by Napoleon, unexpectedly found herself in Russia, where she arrived on July 14, 1812, on the anniversary of the French Revolution and after the beginning of the Patriotic War of 1812. In Russia, she was given the widest hospitality. On August 5, she was even presented to the emperor and empress. And the artist Borovikovsky even painted her portrait. However, on September 7, on the day of the battle of Borodino, she left Saint Petersburg for Stockholm, where the French revolutionary Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, who became King of Sweden, offered her asylum. But even there she did not stay long and soon went to England, where she stayed until Napoleon was defeated. Only then did she return to Paris after a ten-year exile.

Madame de Staël described her impressions of Russia in the second part of her book “Ten Years of Exile” (Dix Années d’Exil). It contains many apt remarks about the character of the Russian people, about the social order of that time, about the life and customs of different classes of society. Alexander Pushkin was, by the way, among admirers of the talent of Madame de Staël. He read a lot of her literary works and highly appreciated her talent.

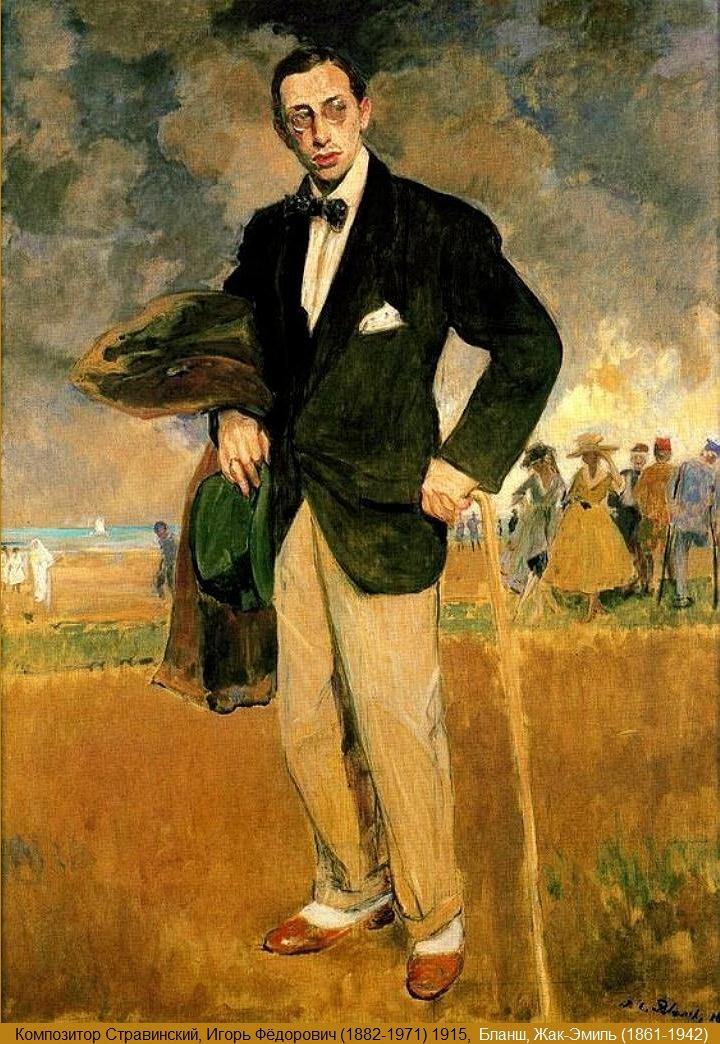

There are many Swiss people who have enriched the great French culture. You can’t list everyone. But one cannot fail to mention the great Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz, a son of a merchant, who graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Lausanne and became one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. Ramuz was highly appreciated by André Gide, Paul Claudel, Jean Cocteau, Stefan Zweig. Many of his novels have been filmed. In a strange way, Ramuz also has a significant presence in Russian culture, for in 1915, during the war, he became friends with the young and brilliant composer Igor Stravinsky and in 1918 wrote an excellent libretto for his operatic work “The Soldier’s Tale”.

Igor Stravinsky was not a single Russian exile who found refuge in hospitable Switzerland. I cannot miss to mention some of them. Many were revolutionaries, but not all of them. Switzerland granted everyone freedom of thought.

Let’s start with Herzen.

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen was one of the very first Russian radical revolutionaries, ardent enemies not only of the autocracy, but also of the very imperial essence of the Russian state.

Herzen, who was a radical republican, found himself in exile on the eve of the February Revolution of 1848, which seemed to him the realisation of all his hopes. The subsequent June uprising of the workers and its bloody suppression shocked Herzen, who became close to Proudhon and other leaders of the revolution and European radicalism. Together with Proudhon, wealthy Herzen published the newspaper “Voice of the People” (La Voix du Peuple) financed by himself.

On June 13, 1849, Herzen took part in a banned protest demonstration in Paris, after which, using the passport of an unknown Romanian, he fled to Switzerland to avoid arrest.

Herzen naturally fit into the radical circles of the European émigrés, who gathered in Switzerland after the defeat of the revolution in Europe. He became famous for his essay book “From the Other Shore”, in which he abandoned past liberal convictions and promoted a specific system of views about the doom of old Europe and the prospects for Russia which was designed to implement the socialist ideal.

In July 1849, Nicholas I arrested all the property of Herzen and his mother as revolutionaries. It was pledged to the banker Rothschild. But rich Herzen escaped poverty, because Rothschild, negotiating a loan to Russia, achieved the cancellation of the emperor’s ban for Herzen, who by that time had become a citizen of Switzerland.

Another great Russian exile of that time was Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin, a thinker, revolutionary, anarchist theorist. Bakunin wrote in his book “God and the State”: “The liberty of man consists solely in this: that he obeys natural laws because he has himself recognized them as such, and not because they have been externally imposed upon him by any extrinsic will whatever, divine or human, collective or individual.” He argued that capitalism and the state in any form were incompatible with the individual freedom of the working class and peasantry. He wrote: “I am a supporter of the Russian people, and not a patriot of the state or the All-Russian Empire.” The figure of Bakunin was contradictory and original in that he opposed Karl Marx and the idea of socialism itself.

He wrote: “Mr. Marx completely underestimates a very important element in the historical development of mankind: the temperament and exclusivity of every race and every people, the temperament and character, which themselves are naturally the products of many ethnographic, climatological, economic, as well as historical reasons, but which, once given, even apart from, and independently of, the economic conditions of each country, have a significant influence on its destinies and even on the development of its economic power.”

Bakunin’s political model was called collectivist anarchism. In it, as in Marxism, the main role was assigned to workers and peasants. However, unlike Marx, Bakunin denied the need for the dictatorship of the proletariat, considering it a threat to the entire idea of social revolution and a prerequisite for a return to authoritarianism. In which, as it turned out, he was right.

It is impossible not to mention here Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Switzerland was Lenin’s last foreign place of residence before his return to revolutionary Russia. Even before emigrating, he often came to Geneva to meet Plekhanov. Also here, in 1903, he managed to launch the newspaper Iskra. Lenin believed that Switzerland “is especially good in general culture and extraordinary conveniences of life.” He loved Switzerland, loved its well-established bourgeois way of life.

The last residence of Lenin in Switzerland was the city of Zurich. At the end of February 1916, Lenin and Krupskaya rented an apartment at Spiegelgasse 14. Almost opposite house No. 11, where great Goethe lived. “Nadya and me are very pleased with Zurich,” Lenin wrote.

In January 1917 the cherished revolution seemed to Lenin so long postponed that he ended one of his reports of that time with the words: “We old people, perhaps, will not live to see the decisive battles of this coming revolution.” Time, as we know, judged otherwise. Less than three months later, Lenin and Krupskaya, Inessa Armand, Zinoviev and his wife, Grigory Sokolnikov, Karl Radek and others, who were leaving in the so-called “sealed carriage”, gathered in Zurich – a total of thirty-one adults and one four-year-old boy. At eleven o’clock in the evening, April 3, Lenin arrived at the Finland Station in Petrograd.

The Zurich episode of Lenin’s life was described in his own way by the great Soviet exile Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. “Lenin in Zurich” became his first book written in exile.

The fate of the great Russian composer, pianist and conductor Sergei Rachmaninoff is also connected with Switzerland. Living and performing primarily in the United States, he frequently toured pre-war Europe and spent much of his time between 1930 and 1940 in Switzerland, where he built the luxurious Villa Senar with a large garden overlooking Lake Lucerne and Mount Pilatus. Ivan Bunin visited this beautiful villa.

Rachmaninoff, like Bunin, longed for the lost old Russia. But the news of the German attack on the USSR made a huge impression on him. Some prominent Russian émigrés rejoiced at Nazi Germany’s perfidious attack on the Soviet Union, believing that “Hitler would liberate Russia from the yoke of the Bolsheviks.” But Rachmaninoff did not think so. During the Great Patriotic War, he specially gave several concerts, the entire collection of money from which he anonymously sent to the Red Army fund and advised all Russian emigrants to contribute too. He donated the money raised at one of his concerts to the USSR Defense Fund with the words: “From one of the Russians, moderate support to the Russian people in their struggle against the enemy. I want to believe, I believe in complete victory.”

With the money of the composer, a combat aircraft was built for the needs of the army. According to some reports, Rachmaninoff even visited the Soviet embassy, willing to go home shortly before his death. But he died two years before the Victory, and therefore, unlike Stravinsky, he could not fulfill his dream.

As you can see, a lot of things connect vast Russia with tiny Switzerland both politically and culturally. Not to mention finance and economics. Because during the years of great confrontations between the USSR and the rest of the world, Swiss banks played the critical mediating role, allowing at least indirect communication between the confronting ideologies and political systems.

Switzerland has always been able to put itself in the spotlight. Even today, the ski resort of Davos is a symbol of modern liberal globalism. For it is in this place that once a year the most influential and powerful people of the globe gather for communication.