History is not at all a search for the ultimate truth, but an expression of the desire to find answers to the pressing questions of our time

Kirill Privalov

“There is no history without secret code,” the ancients said. They were only half right: equally, there is no history without discoveries. Without learning new things. And here many questions arise. What is a secret in history? How are discoveries achieved? And in general, are they the key to cognition?.. Cognition of that very innermost secret. Secret of history.

This issue of Russian Mind, according to our tradition, is rich in historical materials. And the main topic among them is, of course, the history of Arkaim, a complex consisting of a fortified settlement, a burial ground and colonies dated 20th–16th centuries BC (!), which was discovered in the early 1970s in the Southern Urals, in the valleys of the Bolshaya Karaganka and Utyaganka rivers in the Chelyabinsk Oblast of Russia. Following Arkaim, archaeologists found other settlements in the same Ural area. All of them are united by a similar organisation of urban infrastructure, which is well-developed and diverse, and it is no coincidence that scientists called this mysterious civilisation – as it turns out now to be one of the most ancient in the world – the Country of Towns.

“Russia is again the Homeland of Elephants,” an incorrigible skeptic will express his distrust of the above facts. This is his right, not to be taken away. But in fact, Arkaim, the northernmost of the ancient civilisations, is, without a doubt, a huge sensation. However, should we be surprised? The world, with its gigantic glaciations and sharp warmings over distant millennia, is so rich in discoveries that we have to talk not about its rational perception, but about cognition, combining logical comprehension with intuition and even sometimes insight.

It is possible, of course, carefully number all civilisations and proceed from this neat classification in a logical assessment of earthly life, like the guru of philosophy of history, the Englishman Arnold Toynbee who, in particular, saw in the Russian Cossacks some semblance of a medieval knightly order. But is such mental juggling of peoples and nations capable of bringing us closer to understanding the phenomenon of civilisations, closed societies characterised by a set of determining features, which allow us to characterise civilisations? Is it possible today to adapt the history of countries and states to ready-made concepts, to the conventional system of distribution of roles of peoples in the global civilisational theatre that has developed in the perception of some political authorities? No people can be fit in a matrix pre-straightened for them from the outside. It is possible, of course, to remake historical facts, change them beyond recognition, but the essence of the world historical mainstream still cannot be shaken.

Especially now, when archaeologists have truly space technologies at their service. What you sometimes cannot see under your feet, in the dirt and dust, is clearly visible from near-earth orbit. It was not for nothing that the poet asserted: “Big things can be seen from a distance…” Today in different parts of the planet such new cultural and civilisational layers are being discovered over and over again, that historians are quite at a loss.

Not to mention: can history even be considered a 100% objective science? After all, a wide range of opinions and conclusions is expected. It’s no secret: every historian’s text is in one way or another connected with its author, if not with the original chronicler, whose works were, to one degree or another, used as a source for understanding the historical process. Any historical events are seen through the eyes of a historian, who does not simply list them, but dissects them, looking for the causes and connections of these phenomena. How can you not get lost in such a host of facts and comments? After all, as some theorists believe, achieving the objective truth is a process, not a result.

So what? Even the ancients argued that no one is immune to making mistakes. The value of history as a science, that helps us develop our collective memory and national identity, preserve the heritage and traditions of our ancestors, does not diminish in any way. On the contrary, it strengthens that special everyday collective mentality called “patriotism” and confirms the spirit of the state, its ontological foundations.

It is not for nothing that the Russian philosopher and writer Vasily Rozanov wrote: “Loving a happy and cheerful homeland is not a big thing. We must love her precisely when she is weak, small, humiliated, finally, stupid, finally, even vicious.” Nikolai Gogol was even more specific: “If a Russian only loves Russia, he will love everything that is in Russia. God Himself is now leading us to this love. Without the illnesses and suffering that had accumulated in such abundance inside her and which were our own fault, none of us would have felt compassion for her. And compassion is already the beginning of love.” That same love that should not be hidden by the bustle of everyday life, the race for momentary benefits, finally, consumer thinking. To be more specific: love for one’s native country, for one’s fatherland. Including her history, whichever it may be. How can one not recall the lines from Alexander Pushkin’s letter to Pyotr Chaadaev: “…I swear on my honour that for nothing in the world I would want to change my fatherland or have a different history than the history of our ancestors, the way God gave it to us.”

However, time, as we know, flies faster than us. It is rushing, flying, changing! And, perhaps, in the two centuries that have passed since Pushkin’s time, so many things have changed on Earth that the postulates of the ideals of the past no longer work, do they? I’ll be honest: I sincerely doubt it. Moreover, how can one not master the horizons of cognition when there is such a powerful flow of information these days? How to set a time frame for facts, since history exists only where time exists? And what is time like, if you don’t give it time, as the charismatic President of France François Mitterrand once called for?..

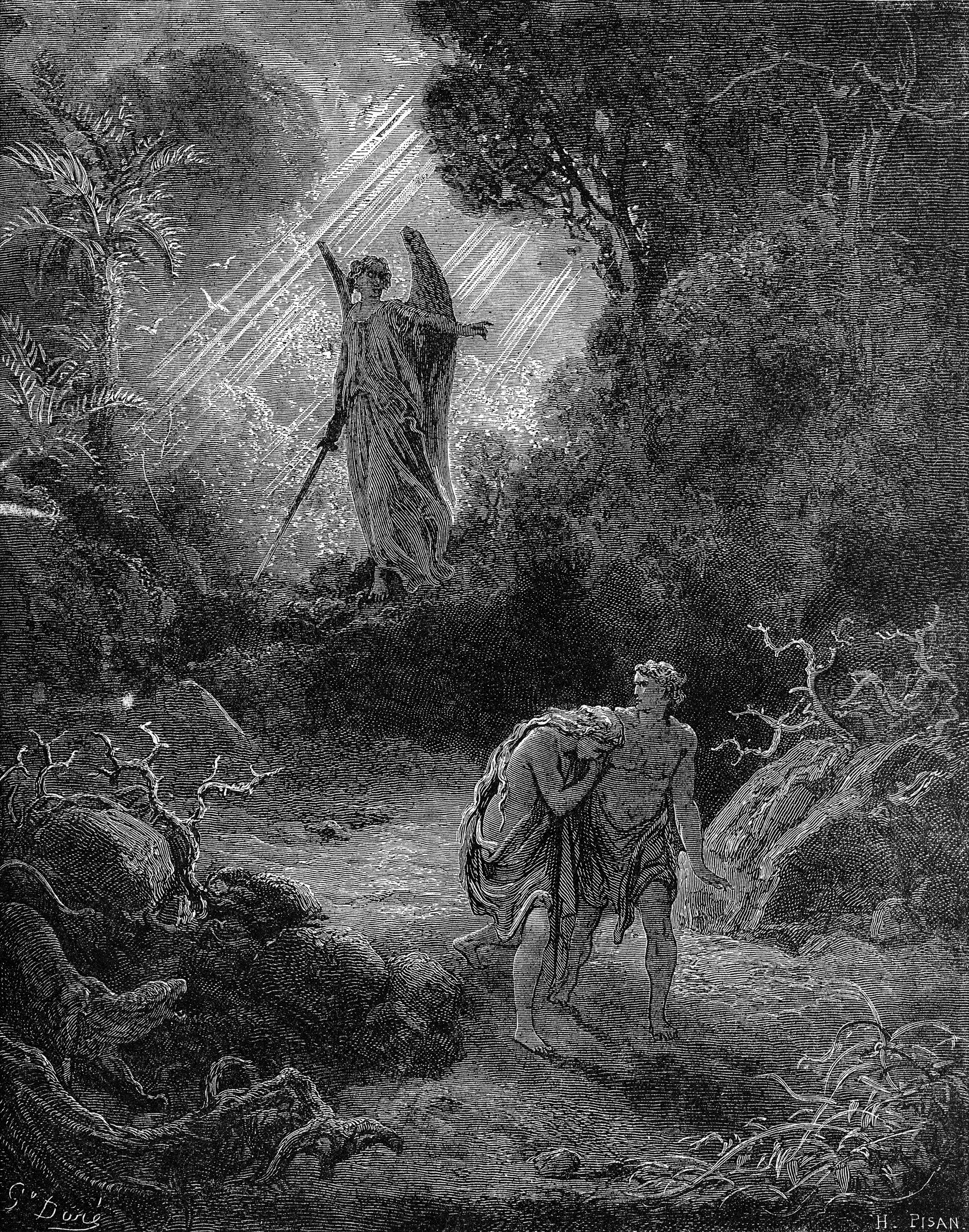

Sophistry, play on words? It seems to me – no. There is simply a desire to give the facts the opportunity to “rest” and put human history into some kind of framework in our usual worldview. After all, according to Christian ideas, history opens not from the moment of the creation of man, but from the moment of his fall into sin, disobedience to the Divine will. Only after the expulsion of people from the paradise, where the existence of Adam and Eve flowed smoothly and peacefully without essential metamorphoses, did history begin. A real, authentic, merciless history, embedded within specific time boundaries. Cognition also arose shyly. Even at the cost of original sin, but still cognition was so sweet, so tempting and, it would seem, so promising.

“A beautiful legend, a textbook myth,” someone would say about the above. However, true stories are usually quickly forgotten, and myths live for centuries, if not millennia – this is an axiom.

“We consider myth as a type of human behaviour and at the same time as an element of civilisation,” wrote the Romanian thinker Mircea Eliade in the middle of the last century. And further: “…If myth is not just an infantile or misguided creation of “primitive” humanity, but an image of a form of being in the world, then what can be said about the myths of our time?” Moreover, history, the interest in which remains great throughout the world today, gives us a huge number of topics for all sorts of new myths. It is not facts that are valued in journalism today, but their comments, conjectures, and therefore myths. And even without them, most likely, there can be no talk of a sincere desire to cognise history along with its “legends of our time.” In the end, history is not at all a search for the ultimate truth, but an expression of the desire to find answers to the pressing questions of our time, even if, for reasons that depend on us or not – no difference, such questions have not yet been fully formulated by us.

I once heard from one of my American colleagues a maxim that I liked as a professional journalist (and therefore, first of all, as an entertaining storyteller): “Who believes that the world consists of atoms is mistaken; it’s actually made of (hi)stories.” That’s right. The continuity of the flow of history that scientists talk about is in fact the inexhaustibility of a collection of histories. In plural! And in each of them, if it is entertaining and rich in symbols, there is a certain secret, there is a plot, there is intrigue. Having discovered one story for ourselves (or imagining that it has finally been discovered), we face another one, even more fascinating, exciting, and sometimes even more mysterious, containing its own secret. Isn’t it wonderful to constantly feel like you’re on the eve of discovery? We at Russian Mind strive to present a discovery to readers in each of our materials. How else? After all, history for us is an act of cognition. Sometimes even somewhat painful, but nevertheless most often pleasant.

However, there is another, completely opposite, point of view. Thus, the famous German philosopher Karl Jaspers believed that “history has a deep meaning, which is inaccessible to human cognition.” Jaspers said: “Between the immeasurable prehistory and the immeasurable future lie 5,000 years of history known to us, an insignificant segment of the boundless existence of man. This story is open to the past and the future… We and our time lie in this history… In terms of the breadth and depth of changes in all human life, our era is of decisive importance. Only the history of mankind as a whole can provide a scale for understanding what is happening at the present time.”

Well, sometimes we also will try to proceed from this postulate. We have significant grounds for the correct approach to understanding history in all its guises. Plunging into the past, we emerge into the future and do not at all want our past to repeat itself in the near or even long term. In this context, the brilliant Russian maxim involuntarily comes to mind, filled with our specific national self-irony: “Everything is ahead of us – and this is what is alarming.” Therefore, having analysed “the affairs of bygone days,” we strive to be as objective and self-possessed as possible when assessing today’s events. And even though the pioneer of the information technology era, American Steve Jobs, convinced his contemporaries that the past did not exist, and the future, most likely, will never come… We, sinners, can only be content with the present, and that suits us for now.

We, Russian people, no matter where we are in the world, live according to a different algorithm: we carefully study the past, optimistically count on the future and try to live and work with dignity in the present. It seems that we have some solid grounds for such a healthy assessment of our modus vivendi. After all, by cognising history, we also cognising ourselves. Is that not right?