The biggest blockbuster in Soviet history, a 7-hour adaptation of War and Peace, is absolutely worth seeing.

In any serious, sober-minded discussion about what could be selected to exemplify the farthest reaches of cinema’s capabilities, War and Peace – Sergei Bondarchuk’s largely unseen adaptation of Tolstoy’s literary classic – would have to be on the table.

The story of its production, of a man moving heaven and Earth to realize a staggering vision, boggles the mind to this day. The adaptation set a new standard for “epic,” capturing all the passion and tragedy of Napoleon’s clash against the Russian aristocracy in its seven-hour sprawl. Anyone who hears “431 minutes of War and Peace” and imagines an airless museum exhibit passing itself off as a film has another thing coming.

The film’s larger-than-life legend begins in 1961, when Bondarchuk commandeered the largest budget the USSR had ever seen for a single motion picture. Released in four parts in 1966 and 1967, it was a colossal success in its original homeland run as well as a worldwide sensation, and playing as a four-night special on ABC in 1972 after having set a new record for highest ticket cost – as steep as $7.50, the equivalent of dropping $56.52 on a ticket today, and a big step up from the $1.20 rate in place at the time – during theatrical screenings of an abridged six-hour edit in the US. The 1966 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film was just the feather in its cap – er, shako.

In 1956, a take on Tolstoy’s doorstopper novel by Hollywood luminary King Vidor inadvertently launched a competition that would yield the seventh art’s high-water mark. Vidor’s version – which tapped Henry Fonda and Audrey Hepburn to carry its 208 minutes – earned plenty of Academy love without the box-office receipts to match. A subtitled version finally made the trek to Russian theaters in 1959.

Still, government apparatchiks didn’t like seeing Fonda and Hepburn’s faces filling their people with ideas about Western excellence. So culture minister Yekaterina Furtseva commissioned a red-blooded production from the homeland that would “surpass the American-Italian one in its artistic merit and authenticity,” as the open letter she published in state press announced. It was to be “a matter of honor for the Soviet cinema industry.”

Sergei Bondarchuk recognized that a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity had fallen into his lap in the form of a blank check drawing on an infinite bank account. Bondarchuk harnessed a nationalist spirit for unprecedented scope. Riding the wave of nationalist sentiment, he put a small fortune of 8.29 million rubles to work on a spectacle that would blow his overseers away. With the administration’s notoriously short patience for failure in mind, he literally directed the film as if his life depended on it.

It’s tough to say definitively, but this critic is fairly certain that no single filmmaker in the medium’s history has ever been granted the level of access afforded to Bondarchuk during War and Peace’s six-year production process. In addition to having a gargantuan sum of money at his disposal, Bondarchuk had his pick of the Soviet Union’s finest playwrights to draw up his script.

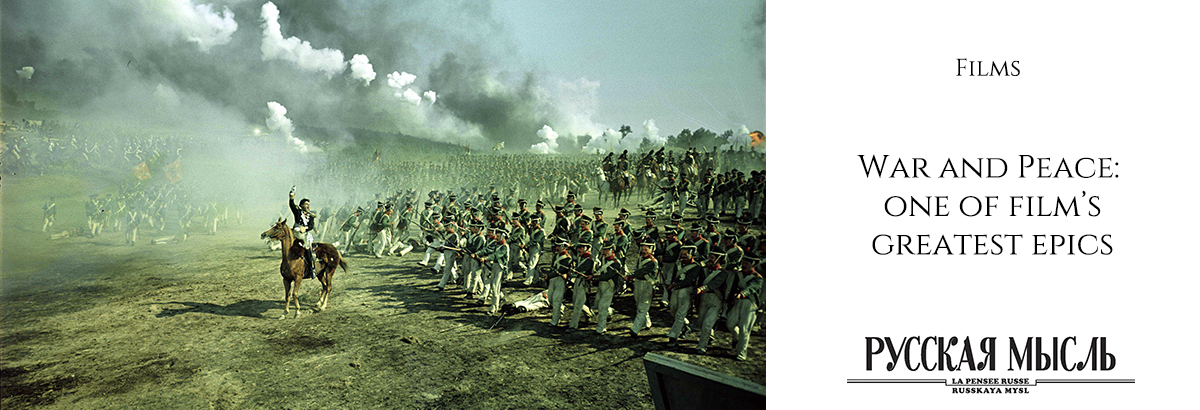

He filled his opulent sets with chandeliers, furniture, and other 19th-century relics on loan from over 40 museums across the USSR. The military advisers acting as Bondarchuk’s consultants gave him the go-ahead to marshal thousands upon thousands of actual soldiers for use as extras in his psychotically ambitious battle scenes. And he cast himself in the lead role of Pierre Bezukhov.

Bondarchuk was insistent upon using the meticulously bred Borzoi dogs for a fox-hunting sequence in keeping with the national tradition, except that the noble-bred species had grown uncommon. He managed to find 16 of them, only to discover that the canines had lost the tracking instinct. His fix? Borrow a pack of wolves from the state zoological department, get some scent hounds from the Ministry of Defense to chase down the wolves, and then send the Borzois to follow the hounds. Convoluted? Yes. Needlessly expensive? Sure, but when you’re working without limits, who could possibly care?

The director’s plan to hook the masses relied on shock and awe, bending even the most stubborn detractors into submission via the sheer magnificence of his vision. Within the tangled web of passion between Natasha Rostova (Lyudmila Savelyeva), Pierre Bezukhov (Bondarchuk), and Andrei Bolkonsky (Vyacheslav Tikhonov), the crew mounted a series of astonishing set pieces, continually topping themselves.

The fox-hunting bit that Bondarchuk worked so hard on came out like a psychedelic swirl of gnashing teeth and gaping eyeballs, and early clashes at Austerlitz and Schöngrabern tease the viewer with a taste of the sum total of the film’s might. For his grand finale, Bondarchuk recreated the burning of Moscow by razing a vast swath of land in a village just outside the city. The terror in the eyes of the extra dashing alongside Pierre through the inferno appears as authentic as it gets. Say what you will about the wonders of CGI, but sometimes there’s just no substitute for the real thing.

Bondarchuk’s staging of the conflicts between the Napoleonic and Russian forces make Apocalypse Now look like a particularly audacious senior thesis film.

Virtuosic camerawork rendered each scene of Bondarchuk’s War and Peace its own sort of spectacle. Aerial shots that stretch out for miles survey the full breadth of Bondarchuk’s army, assuming a God’s-eye-view so that he may squeeze as many bodies into a frame as possible. On the ground, custom rigging enabled how-the-hell-did-he-do-that tracking shots, wending in and out of bayonet stabbings, horse deaths, and chains of detonations to capture all the hysteria in these orgies of brutality. It might have taken approximately the same amount of effort and resources to mount an actual ground invasion.

In July 1965, War and Peace was awarded the Grand Prix at the 4th Moscow International Film Festival together with the Hungarian entry Twenty Hours. Ludmila Savelyeva was presented with an honorary diploma.[86] The readers of Sovetskii Ekran, the official publication of the State Committee for Cinematography, chose Savelyeva and Vyacheslav Tikhonov for the best actress and actor of 1966, in recognition of their appearance in the picture. In the same year, War and Peace also received the Million Pearl Award of the Roei Association of Film Viewers in Japan.

In 1967, the film was entered into the 1967 Cannes Film Festival, outside of the competition. It was sent there instead of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, which was invited by the festival’s organizers but deemed inappropriate by the Soviet government.

In the United States, it won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film in the 26th Golden Globe Awards. The picture was the Soviet entry to the 41st Academy Awards, held on 14 April 1969. It received the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and was nominated for the Best Art Direction.

War and Peace was the first Soviet picture to win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and was the longest film ever to receive an Academy Award until O.J.: Made in America won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2017.

It also won the National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Foreign Language Film for 1968.

In 1970, it was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Production Design in the 23rd British Academy Film Awards.

The film has often been considered the grandest epic film ever made, with many asserting its monumental production to be unrepeatable and unique in film history.

Though he’d been appointed a de facto keeper of the cultural gates, Bondarchuk found plenty of room to get his own kicks through indulgent formal experimentation. The scenes of dialogue bristle with their own weird sense of artistry and beauty. Even the barren snow has been shot with a lushness that imbues a majesty in the blankness, and the footage is gussied up with double-exposures predating the arrival of the word “trippy” in the Russian language.

At the conclusion of the film’s second segment, Bondarchuk plays around with rhythm by inserting a split-second shot of a jingling chandelier to punctuate Pierre’s initial courtship of Natasha. One of the most indelible scenes takes place during a roaring night of revelry among the nobles, as Bondarchuk literalizes their stupor with aggressive, whirling cinematography to make a tornado out of their party. It’s gloriously disorienting, and still, it’s hard to miss the real live bear chugging a stein of beer. One might wonder what this bear is doing, tearing it up with human beings, but Bondarchuk’s is a film of “why not?” and not “why?”

Like In Search of Lost Time or Infinite Jest, War and Peace is preceded by an intimidating reputation. Clocking in at north of 1,200 pages and boasting hundreds of characters (many of whom share tough-to-keep-straight family names), it still scares off all but the most determined readers. There’s the old cocktail party line about highbrow types who split their lifetime into two periods: before and after they conceded they’d never read Proust; it’s easy to succumb to the same self-limitations with Tolstoy.

Bondarchuk wasn’t playing to the monocle-polishers, however. His goal was nothing less than for every living citizen of Russia – if not the world – to see his movie, preferably multiple times. He wanted the finished product to be opulent, titanic, heartbreaking and above all, compulsively watchable. Along with screenwriter Vasily Solovyov, he pruned a handful of the original novel’s subplots and worked the thorny historical philosophizing into a palatable episodic structure. Much in the same respect that Shakespeare pitched himself first and foremost to the groundlings, Bondarchuk fancied his work something closer to a prestigious binge-watch than a lofty high-culture object.

The film was produced by the Mosfilm studios between 1961 and 1967, with considerable support from the Soviet authorities and the Red Army which provided hundreds of horses and over ten thousand soldiers as extras. At a cost of 8.29 million Soviet rubles – equal to US$9.21 million at 1967 rates, or $60–70 million in 2019, accounting for ruble inflation – it was the most expensive film made in the Soviet Union. Upon its release, it became a success with audiences, selling approximately 135 million tickets in the USSR.

Principal photography began оn 7 September 1962, the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino/