Dr. Augustine Sokolovski, Doctor of Theology, Priest

Christ is risen! He is risen indeed! In this year of 2021 the Orthodox Church celebrates Easter on May 2. This is one of the latest possible dates for the celebration of Easter throughout the year. As known, Easter is celebrated on the first full moon after the vernal equinox. According to the Julian calendar the date of the equinox is 13 days later and falls on April 4. This Easter also falls in the period between April 4 and May 7.

According to the Creed of Nicea and Constantinople (381), Jesus “was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered, and was buried, and the third day he rose again, according to the Scriptures”. For Orthodox Christians the celebration of Easter is a cause for reflection about the mysteries of our faith. One of the signs of the presence of the Easter mystery in the Gospel is the tomb of Lord Jesus. “Quickly Peter and the other disciple went to the tomb. They both ran away together; but the other disciple ran faster than Peter and came to the tomb first. He stooped down, saw the veils lying; but he did not enter the tomb” (John 20,3).

The story of the Resurrection of the Lord Jesus, as it is described in the Gospel, is preceded by the pilgrimage of the disciples and the women disciples – myrrhbearers – to the tomb which turns out to be empty. “Early on the first day of the week, Mary Magdalene comes to the tomb while it was still dark and sees that the stone is taken away from the tomb. She runs to Simon Peter, and another disciple whom Jesus also loved, and says to them, ‘They have taken the Lord away from the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him’” (John 20;2). The emptiness of the Lord’s tomb is a very important aspect of the Easter event, a particular topic of the faith of the early apostolic Church, that we absolutely must catch.

Otherwise, we may end up with a misunderstanding so inappropriately used by some contemporary preachers. “The emptiness of the Holy Sepulchre in the Gospel” – say these – represents a kind of prototype and even a legitimation (i.e. justification) of the empty churches in the times of the secularisation we are currently experiencing. The tomb of Jesus is empty but filled. It is filled with sacramental presence. And its emptiness is the place of this real presence, of meaning and life.

However, every tomb and grave site is a place of recognition of the fact that the person we loved is not there anymore. It testifies in a very radical way that the human time and the exodus which took place are irreversible. The crucial point of the Gospel accounts of the pilgrimages of the disciples and myrrhbearers to the Holy Sepulchre is that – in the perception of the apostolic community – the Savior’s tomb was designated from the beginning as a place of presence. “Simon Peter comes after him, enters the tomb, sees some shrouds lying, and the board that was on his head, not lying with the shrouds, but rolled up in another place. Then came in another disciple who had come before unto the sepulcher, and saw, and believed. For they did not yet know from the Scriptures that he was to be raised from the dead” (John 20:8-9). The Tomb of the Lord Jesus was the place of presence of whom “who suffered and was buried”, as it is said in the Creed.

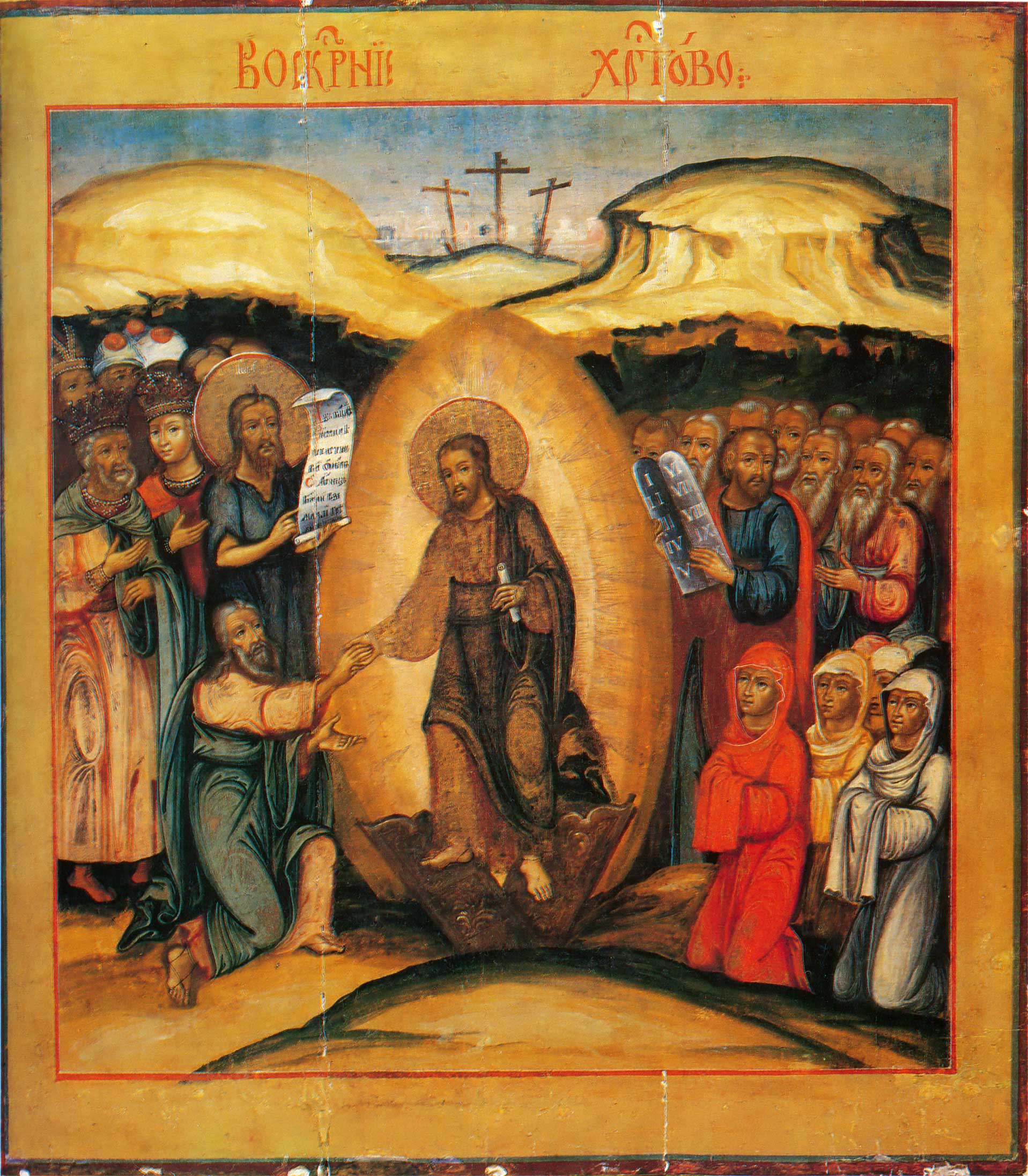

The disciples, not yet knowing or being certain of the resurrection, come again and again to the Tomb in order to expose themselves to the paschal light that had been shining from the Holy Sepulchre of the Lord Jesus. “Suddenly there was an earthquake. For an angel of the Lord came down from heaven, rolled aside the stone, and sat on it. His face shone like lightning and his clothing was as white as snow” (Mt.28;2-3). The earthquake, the fear of the Roman soldiers, the withdrawal of the stone, the shrouds lying in the place of the body of the Lord became the beginning of the Church.

Between the approach to the Holy Sepulchre and the appearance of the Risen Lord – a new eve of the Resurrection – there was some time. The time that represented the great mystery of the Church as the very place of all human history. In the Holy Sepulchre, together with the angels, were all those who had already experienced the blessing of the Lord. They remained waiting. “The women who had come with Jesus from Galilee followed Joseph and saw the tomb. They rested on the Sabbath in obedience to the commandment” (Luke 23;55-56).

All those whom the Lord healed, to whom he did good in his earthly life. The lepers, whom he cleansed; the sinners, whom he forgave; the crippled and paralysed, whom he raised; the dead – and with them their leader Lazarus – whom he raised. The forgotten, the outcasts, all “The Cursed and Killed” – as the title of Victor Astafjev’s (1924-2001) novel reads – were already illuminated by the Gladsome Light of the eve of the Resurrection. All of them reminded the apostles and women disciples, who were coming and going and again in this sacramental pilgrimage, what they themselves had experienced with Jesus. They testified that death could not hold Him back. “And many bodies of the saints who had died arose and came out of the tombs after His Resurrection and went into the holy city and appeared to many” (Matthew 28:53).