The Battle of Stalingrad marked the beginning of a radical turning point not only in the course of the Great Patriotic War, but of the Second World War in general

Sergei Aptreikin, Master of History, Associate Professor, Leading Researcher of the Research Institute (Military History) of the Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia

The military history of Russia has seen many examples of courage, heroism, military valour of soldiers on the battlefield and the strategic genius of military leaders. The Battle of Stalingrad stands out against their background.

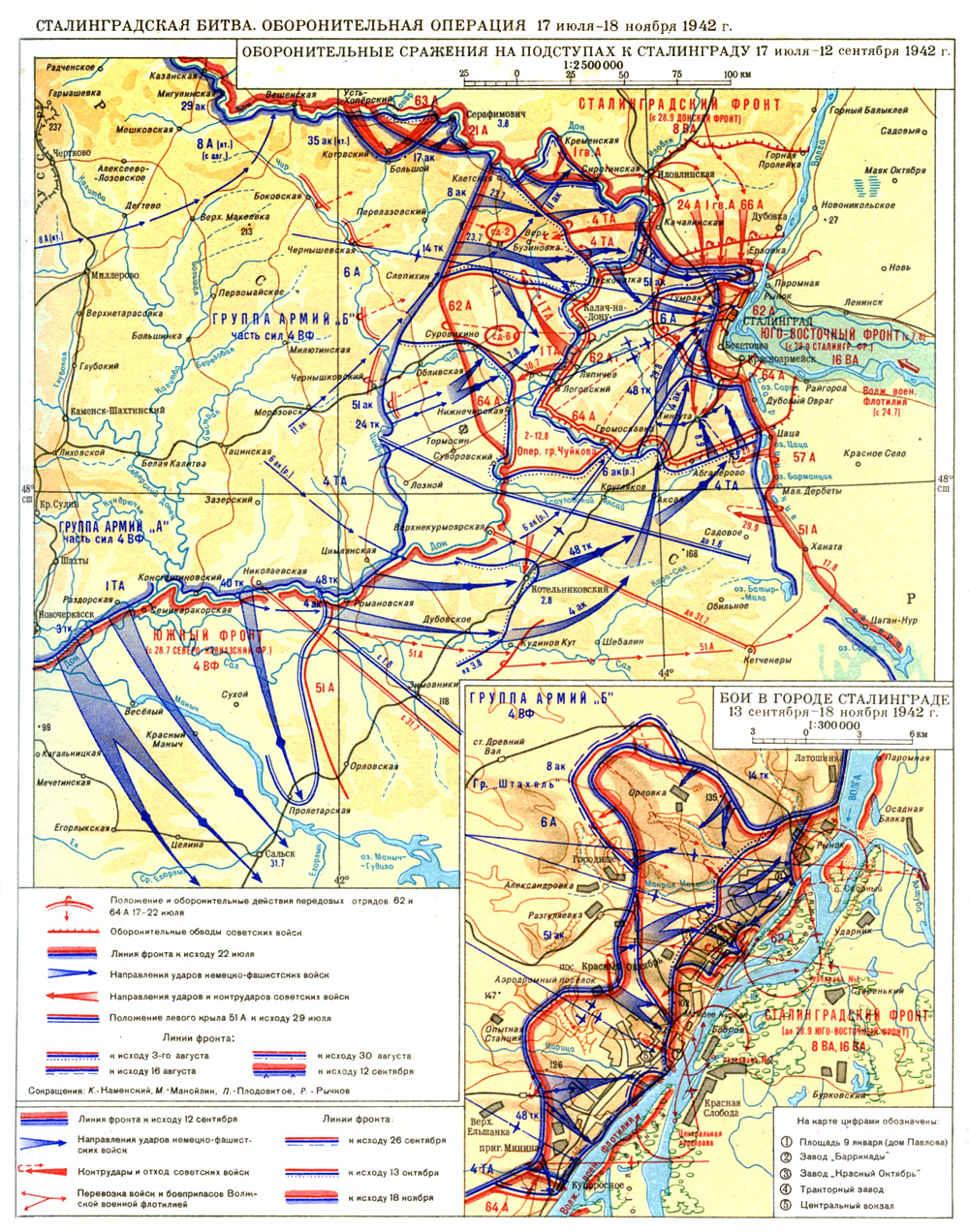

The period of defence: 17 July – 18 November 1942

This brutal battle went on for 200 days and nights on the banks of the Don and the Volga, and then at the walls of Stalingrad and in the city itself. It unfolded over a vast territory of about 100,000 square kilometres with a front length of 400 to 850 kilometres. Over 2.1 million people were involved in this grandiose battle on both sides at different stages of hostilities. In terms of goals, scope and intensity of hostilities, the Battle of Stalingrad surpassed all previous battles in world history.

While planning operations for the summer and autumn of 1942, the German High Command was guided by Directive no. 41 signed by A. Hitler on 5 April 1942, in which the stated military and political goals were actually a development of the ideas of Operation Barbarossa. The main conditions for the final defeat of the USSR, according to the Wehrmacht top leaders, were the capture of the Caucasus with its large oil deposits, the fertile agricultural regions of the Don, Kuban, the North Caucasus and the Lower Volga region, along with the capture of the water artery – the River Volga.

By the end of June 1942, the enemy had concentrated about 900,000 soldiers and officers, 1,260 tanks, 17,000 guns and mortars, and 1,640 combat aircraft in the area from Kursk to Taganrog at a front of 600–650 kilometres. These forces amounted to 35% of infantry and over 50% of tank and motorised divisions of the total number of troops on the Soviet-German front.

In accordance with the Wehrmacht High Command’s Directive no. 45 of 23 July 1942, Army Group South was split into two groups in preparation for the offensive: Army Group A and Army Group B. Army Group A (under Field Marshal V. List) was tasked with capturing the Caucasus. As prescribed by the directive, ‘…Along with the equipment of defensive lines on the Don River, the task of Army Group B is to strike at Stalingrad and defeat the enemy forces concentrated there, capture the city, block the isthmus between the Don and the Volga and disrupt transportation down the river. Following this, tank and mechanised troops should strike along the Volga with the aim of reaching Astrakhan and paralysing traffic along the main channel of the Volga…’ Army Group B (under Colonel General, from 1 February 1943, Field Marshal M. Weichs) contained: the German 4th Panzer, the 2nd and the 6th Armies, the 8th Italian and the 2nd Hungarian Armies.

The 6th Army (under Colonel General F. Paulus) was composed of the troops of Army Group B and appointed to capture Stalingrad. The German Command was so confident in the quick capture of Stalingrad that between 1 and 16 July the 6th Army was reduced from twenty to fourteen divisions. In total, by the beginning of the offensive, the 6th Army had 270,000 soldiers and officers, about 3,000 guns and mortars and about 500 tanks, and from the air it was supported by 1,200 combat aircraft of Air Fleet 4.

As a result of the unsuccessful outcome of operations for the Soviet troops near Kharkov, in the Voronezh direction and in the Donbass, coupled with the advance of large enemy forces towards a big bend of the Don, a real threat of an enemy breakthrough to the Volga was created. This could have led to a break in the front of the Soviet troops and the loss of communications linking the country’s central regions with the Caucasus.

The troops of the Southwestern Front suffered heavy losses and could not stop the advance of the Nazi troops to the east. The troops of the Southern Front, repelling the attacks of the formations of the German 1st Panzer and the 17th Armies of Army Group A from the east, north and west, retreated to the Rostov defensive region with heavy fighting. Urgent, decisive measures were needed to organise a repulse of the enemy in the Stalingrad and Caucasus directions.

For this purpose, by decision of the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command the 62nd, 63rd and 64th Armies were deployed in the rear of the Southwestern and Southern Fronts. On 12 July, a new Stalingrad Front was formed (under Marshal of the Soviet Union S.K. Timoshenko), which, in addition to the mentioned armies, contained the 21st and the 8th Air Armies from the disbanded Southwestern Front. The Stalingrad Front was appointed to create a strong defence along the left bank of the Don in the strip from Pavlovsk to Kletskaya and further along the defensive line from Kletskaya, then to Surovikino and Verkhne-Kurmoyarskaya. The 51st Army of the North Caucasian Front was advanced to the sector from Verkhne-Kurmoyarskaya to Azov (over 300 kilometres long) along the left bank of the Don. Together with the Southern Front’s retreating troops, it was supposed to cover the Caucasian direction. Soon, the Headquarters added the 28th, 38th and 57th Armies, which had retreated with heavy losses, to the Stalingrad Front. Ten aviation regiments (a total of 200 aircraft) were sent to reinforce the 8th Air Army in the Stalingrad region.

It should be noted that the tardy revelation of the enemy’s intentions to capture Stalingrad in the summer of 1942 resulted in the Supreme Command Headquarters not having enough time to transfer reserves in time to create a new defence front. In mid-July, twelve divisions of the 63rd and the 62nd Armies (166,000 people, 2,200 guns and mortars and about 400 tanks) could really resist the enemy in the Stalingrad direction. The aviation of the front consisted of about 600 aircraft, including 150–200 long-range bombers and sixty air defence fighters. On the outskirts of Stalingrad four defensive lines were built: the outer, middle, inner and urban ones. Though it was impossible to equip them fully by the beginning of the defensive operation, they played a significant role in the defence of the city. From among the people of Stalingrad, people’s militia battalions were formed.

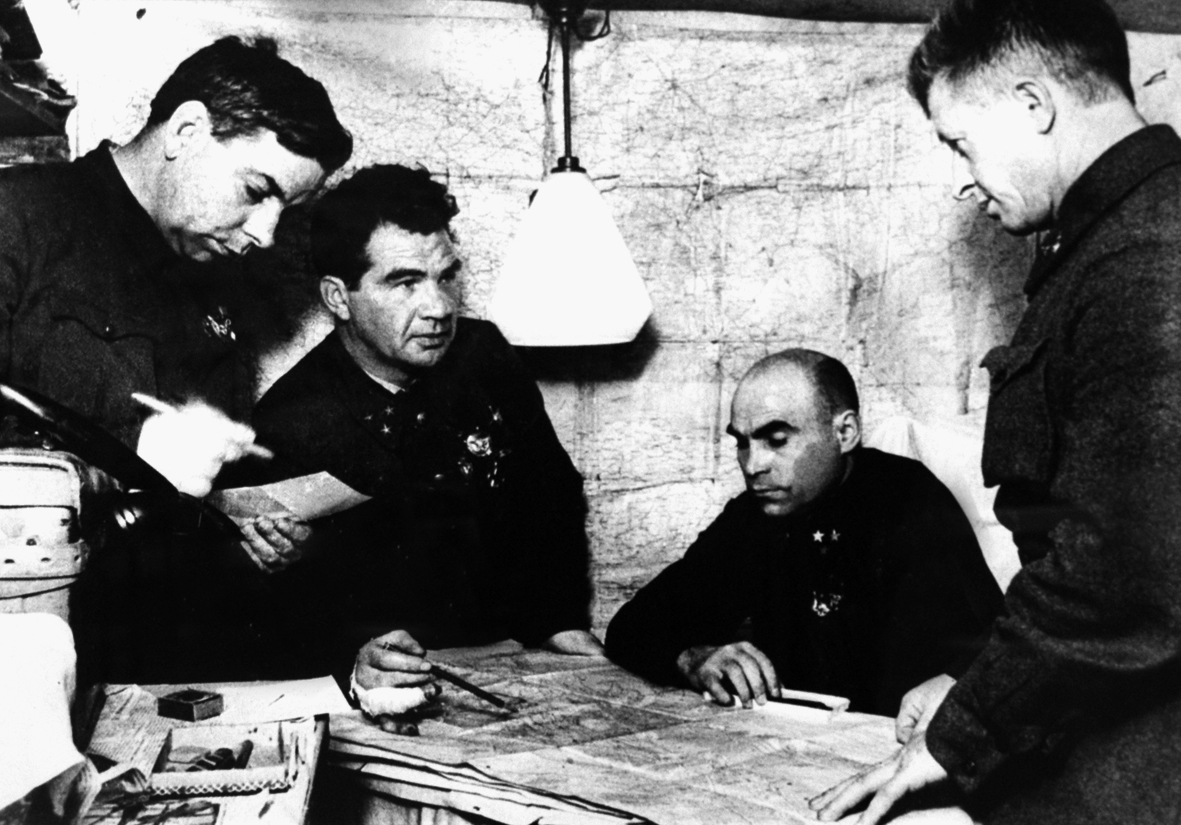

The general leadership and coordination of actions of the fronts near Stalingrad, on behalf of the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command, was carried out by the Deputy Supreme Commander-in-Chief, General of the Army G.K. Zhukov and the Chief of the General Staff, Colonel-General A.M. Vasilevsky.

Given the tasks to be solved, the distinctive characteristics of the conduct of hostilities by the parties, the spatial and temporal scales, along with the results, the Battle of Stalingrad is divided into two periods: the defensive (17 July – 18 November 1942) and the offensive (19 November 1942 – 2 February 1943).

The strategic defensive operation in the Stalingrad direction lasted 125 days and nights and had two stages. The first stage was the conduct of defensive combat operations by troops of the fronts on the distant approaches to Stalingrad (17 July – 12 September). The second stage was the conduct of defensive operations to hold Stalingrad (13 September – 18 November 1942).

The German Command delivered the main blow with the 6th Army forces in the Stalingrad direction along the shortest path through the large bend of the Don from the west and southwest, right in the defence areas of the 62nd (under Major General V. Ya. Kolpakchi, from 3 August – Lieutenant General A. I. Lopatin, from 6 September – Major General N. I. Krylov, from 10 September – Lieutenant General V. I. Chuikov) and the 64th (under Lieutenant General V. I. Chuikov, from 4 August – Lieutenant General M. S. Shumilov) Armies. The operational initiative was in the hands of the German High Command with almost a twofold superiority of numbers and resources.

Defensive combat operations by the troops of the fronts on the distant approaches to Stalingrad (17 July – 12 September)

The first stage of the operation began on 17 July 1942, in a large bend of the Don, with combat contact between units of the 62nd Army and the advance detachments of German troops. Fierce fighting ensued. The enemy had to deploy five divisions out of fourteen and spend six days to approach the main line of defence of the troops of the Stalingrad Front. However, under the onslaught of superior enemy forces, Soviet troops were forced to retreat to new, poorly equipped or even unequipped lines. But even under these conditions, they inflicted significant losses on the enemy.

By the end of July the situation in the Stalingrad direction continued to be very tense. German troops surrounded both flanks of the 62nd Army, reached the Don in the Nizhne-Chirskaya area, where the 64th Army held defence, and created the threat of a breakthrough to Stalingrad from the southwest.

Under these conditions, on 28 July 1942, Order no. 227 of the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command was given to the troops of the Stalingrad and other fronts. The order outspokenly showed a very hard situation not in favour of the USSR, particularly in the Stalingrad direction. Here are excerpts from the order:

‘…The German invaders penetrate towards Stalingrad and the Volga and want to take the Kuban and the North Caucasus with their oil and grain at any cost. The enemy has already captured Voroshilovgrad, Starobelsk, Rossosh, Kupyansk, Valuyki, Novocherkassk, Rostov-on-Don, half of Voronezh…

We have lost over 70 million people, over 800 million pounds of grain annually and over 10 million tons of metal annually. We no longer have predominance over the Germans in human reserves and in reserves of grain. To retreat further means to waste ourselves and at the same time waste our Motherland. Each new piece of land left by us will strengthen the enemy and weaken our defence and our Motherland to the utmost…

It follows from this that it is time to finish retreating. NOT ONE STEP BACK! This should now be our main slogan. From now on, iron discipline must be demanded of every commander, Red Army soldier and political officer: NOT A STEP BACK WITHOUT BEING ORDERED BY THE HIGH COMMAND…

This order must be read in all companies, cavalry squadrons, batteries, squadrons, commands and headquarters.

The People’s Commissar of Defence, I. Stalin.’

In connection with the increased width of the defence zone (about 700 kilometres), by the decision of the Supreme Command Headquarters, the Stalingrad Front, commanded by Lieutenant General V.N. Gordov from 23 July, on 5 August was divided into the Stalingrad and the South-Eastern Fronts. To achieve closer cooperation between the troops of both fronts, from 9 August the Stalingrad Front was put under the commander of the troops of the South-Eastern Front, Colonel General A. I. Eremenko.

On 30 July, the German High Command decided to turn the 4th Panzer Army from the Caucasian direction to Stalingrad. As a result, two armies were operating in the Stalingrad direction: the 6th from the west and the 4th Tank Regiment from the south-west. On 5 August, the advance formations of the 4th Panzer Army reached the outer Stalingrad line. The enemy attempts to break through this line on the move were repulsed by well-organised counterattacks of the formations of the 64th and the 57th Armies.

Despite the stubborn resistance of the Soviet troops, on 23 August the enemy managed to break through the defences of the 62nd Army and approach the city’s middle defensive line, and the advance detachments of the German 14th Panzer Corps managed to reach the Volga north of Stalingrad in the Yerzovka area. At the same time, the Germans threw an armada of bombers on the city – over 2,000 sorties in one day. Throughout the war air raids were not as intensive. The huge city, stretching fifty kilometres, was engulfed in flames.

The Headquarters of the Supreme High Command’s representative A.M. Vasilevsky recalled: ‘The unforgettable tragic morning of 23 August found me in the troops of the 62nd Army. On that day, the Nazi troops managed to reach the Volga with their tank units and cut off the 62nd Army from the main forces of the Stalingrad Front. Simultaneously with the breakthrough of our defence, the enemy bombed the city heavily on 23 and 24 August, for which almost all the forces of his 4th Air Force were involved. The city was reduced to ruins. Telephone and telegraph communications were broken, and on 23 August I had to conduct short talks with the Supreme Commander-in-Chief openly over the radio twice.’

On 23 August alone, 120 enemy aircraft were shot down by air defence systems, of which ninety were shot down by fighter aircraft, and thirty by anti-aircraft artillery. At the same time, anti-aircraft artillery regiments in front of the city repelled repeated attacks by German tanks and infantry, inflicting damage on them. The fighting outside the city walls was extremely intense and violent.

In those days the city defence committee, headed by the First Secretary of the Stalingrad Regional Committee of the Communist Party A.S. Chuyanov, addressed the city residents with an appeal:

‘Dear comrades! Native Stalingraders! Again, like twenty-four years ago, our city is going through hard days. The bloody Nazis are rushing towards sunny Stalingrad to the great Russian River Volga. Stalingraders! Let us not allow the Germans to devastate our native city. Let us all stand as one to protect our beloved city, our home, our family. Let us barricade all the streets. Let us transform every house, every block and every street into an impregnable fortress. Everybody go and build barricades! In the terrible year 1918 our fathers defended Tsaritsyn. Let us also defend red-bannered Stalingrad in 1942!

Everyone go and build barricades! All who are able to carry arms, go and protect your native city and home!’

The people of the city were the most important source of replenishment of the ranks of the defenders of Stalingrad. Thousands of Stalingraders joined the units of the 62nd and the 64th Armies, entrusted with the defence of the city.

In the first days of September the enemy broke through the city’s inner defensive line and captured some areas in its northern part. The Nazis went on to rush to the city centre stubbornly in order to cut off the Volga completely – the most important means of communication. All attempts to break through to the Volga on a broad front cost the enemy heavy losses. So, in just ten days of September, at the walls of Stalingrad the Germans lost 24,000 people in killed, and about 500 tanks and 185 guns were destroyed. Between 18 August and 12 September over 600 enemy aircraft were shot down on the near approaches to the city.

On 12 September, the commander of Army Group B and the commander of the 6th Army were summoned to the Fuhrer’s headquarters near Vinnitsa. Hitler was extremely disappointed that Stalingrad had not yet been taken by the German troops and ordered to capture the city as soon as possible.

The enemy forces were constantly growing. In total, about fifty divisions were already operating in the Stalingrad direction in the first half of September. The Nazis had air supremacy, making between 1,500 and 2,000 sorties a day. Methodically destroying the city, the enemy tried to undermine the morale of the troops and the population.

Defensive actions to hold Stalingrad (13 September – 18 November 1942)

The second stage of the Soviet troops’ defensive operation to hold Stalingrad began on 13 September and lasted seventy-five days and nights. At this stage of the operation the enemy went over to storm the city four times, trying to capture it on the move.

The first assault on the city began on 13 September with a powerful artillery preparation supported by aviation. The enemy outnumbered the 62nd and the 64th Armies in numbers and resources by about 1.5-2 times and in tanks by six times. His main efforts were aimed at capturing the city centre with access to the Volga in the area opposite the central crossing.

The fighting in the city was extremely violent and intense and continued almost round the clock in Stalingrad’s streets and squares. Even the Wehrmacht generals were amazed at the stamina and perseverance of the Soviet troops. A participant in the Battle of Stalingrad, German General G. Derr later wrote: ‘A fierce struggle was waged for every single house, workshop, water tower, embankment, wall, basement, and even heap of rubbish, which had no equal even during the First World War with its gigantic expenditure of ammunition. The distance between our troops and the enemy was extremely small. Despite our massive air and artillery assault, we could not leave the close combat area. The Russians were superior to the Germans in terms of terrain and camouflage and were more experienced in barricade fighting behind individual houses: they took up a solid defence.’

The day of 14 September went down in history as one of the critical days of the heroic defence in the Battle of Stalingrad. Particularly fierce battles were fought in the area of the grain elevator and the Stalingrad-2 Station. At the cost of heavy losses, on 15 September, the enemy captured the dominant height in the central part of the city called Mamayev Kurgan (‘Mamai’s Tumulus’), also known as Height 102. However, the next day units of the 13th Guards and the 112th Rifle Divisions as a result of violent fighting recaptured the height from the enemy.

Between 13 and 26 September, the enemy managed to push the formations and units of the 62nd Army and break into the city centre, and where the two armies (the 62nd and the 64th) met – to move to the Volga. But the enemy did not succeed in taking control of the entire bank of the Volga near Stalingrad. The fighting for control of the railway station was particularly fierce, and it passed from hand to hand thirteen times.

The headquarters of the Supreme High Command constantly reinforced the defending troops with reserves from the depths of the country. Thus, between 23 July and 1 October, fifty-five rifle divisions, nine rifle brigades, seven tank corps and thirty tank brigades arrived in the Stalingrad Front.

In connection with the increased composition of the fronts and the great length of their zones, on 28 September the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command abolished the unified command of the South-Eastern and the Stalingrad Fronts and renamed the Stalingrad Front to the Don Front (under Lieutenant General K. K. Rokossovsky), and the South-Eastern Front to the Stalingrad Front (under Colonel General A. I. Eremenko).

The second assault on Stalingrad was undertaken by the enemy from 28 September to 8 October. The German High Command demanded that Paulus take Stalingrad at any cost and in the coming days. Speaking in the Reichstag on 30 September 1942, Hitler declared: ‘We will storm Stalingrad and take it – you can count on it… If we have occupied something, we cannot be moved from there.’

The fighting at the walls of Stalingrad raged with unrelenting force. Between 27 September and 4 October, deadly fighting took place on the northern outskirts of the city for the workers’ settlements of Krasny Oktyabr and Barrikada. At the same time, the enemy was attacking in the city centre in the Mamayev Kurgan area (he managed to take a foothold on the western slope) and on the right flank of the 62nd Army in the Orlovka area. The pace of German units’ advance during the day ranged from 100 to 300 metres.

In the first days of October 1942, the formations and units of the 62nd Army took defensive positions along the right bank of the Volga in a strip twenty-five kilometres wide. Meanwhile, the distance between the front edge and the water’s edge was no more than 200 metres in some sections. Though the territory of five out of seven city districts was in enemy hands, the Nazis did not manage to take the central embankment with crossings through which the city received troops, weapons, food and fuel and the wounded were sent.

The German High Command was extremely displeased with the actions of the 6th Army in Stalingrad and hurried its commander to capture the entire city as quickly as possible. During the first half of October, it transferred additional forces from Germany to reinforce the 6th Army: 200,000 reinforcements, thirty artillery battalions (about 1,000 guns), thirty engineering assault battalions designed to storm the city and conduct street fighting. Numbers and resources were four or five times greater than those of the 62nd Army.

The third and most fierce assault on the city began on 14 October, using a large amount of firepower. Formations and units of the 62nd Army, even separated from each other by the enemy, continued to defend the strip stretched along the embankment of the Volga. The 138th Rifle Division (under Colonel I. I. Lyudnikov), cut off from the main forces of the army, held the strip along the coast – 700 metres along the front and 400 metres deep. The division consisted of only 500 personnel.

The enemy managed to take the summit and the northern and southern slopes of Mamayev Kurgan. From 28 September 1942 to 26 January 1943, its eastern slope was defended by units of the 284th Infantry Division (under Colonel N.F. Batyuk), repulsing several enemy attacks a day in October and November.

The violence of the confrontation reached its culmination. Fighting went on for every quarter, lane, house and metre of land. In one house Soviet and German units could occupy different floors. The feats of the fighters of the Pavlov’s House residential building, who held it for fifty-eight days, gained worldwide fame. The enemy attacked the house with aircraft, conducted artillery and mortar fire, but the defenders did not retreat a single step. There were representatives of many nationalities among the defenders of Pavlov’s House: eleven Russians, six Ukrainians, a Georgian, a Kazakh, an Uzbek, a Jew and a Tatar.

All the personnel from soldier to generals were filled with one desire – to destroy the enemy who was encroaching on the freedom and independence of their Motherland. The words of the sniper V. G. Zaitsev became the motto for all Soviet soldiers: ‘For us, the 62nd Army soldiers and commanders, there is no land beyond the Volga. We have stood and will stand to death!’ After the Battle of Stalingrad V. G. Zaitsev was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

For a whole month, intense fighting went on throughout the defence zone of the 62nd and the 64th Armies, but the enemy did not manage to break through the defences of the Soviet troops. Only in some areas, advancing a few hundred metres, did the Nazis move to the Volga. Having suffered heavy losses, despite a significant superiority in numbers and firepower, the German troops did not manage to take the whole city, including its coastal area.

However, unwilling to recognise obvious failure of their plans to capture Stalingrad, Hitler and his entourage continued to demand a new offensive from the troops.

The fourth assault on Stalingrad began on 11 November. Five infantry and two tank divisions were thrown into the battle against the 62nd Army. The position and conditions of the 62nd Army were extremely hard. It consisted of 47,000 troops, about 800 guns and mortars and nineteen tanks. By this time, its line of defence had been divided into three parts.

This is how a German officer and a battalion commander saw the picture of fierce offensive action: ‘…Volleys are falling on Russian positions one after another. There should no longer be anyone alive. Heavy guns are firing permanently. Bombers with black crosses are rushing towards the first rays of the rising sun in the brightening sky… They dive and drop their bomb loads on the target with thunder… Some twenty more metres, and they (German infantry) will occupy advanced Russian positions! And suddenly they lie down under a hurricane of fire. To the left, machine guns are firing in short bursts. Russian infantry (which we believed to be destroyed) appears in shell-holes and firing points. We can see Russian soldiers’ helmets. Every moment we see our advancing soldiers fall on the ground never to get up, with rifles and machine guns falling from their hands.’

There were no long pauses or lulls in combat on the territory of Stalingrad – it went on continuously. For the Germans Stalingrad was a ‘mill’, which ‘ground down’ hundreds and thousands of German soldiers and officers, destroying tanks and planes. Some German soldiers’ letters describe the situation of combat in the city figuratively yet realistically: ‘Stalingrad is hell on earth or another Verdun – Red Verdun with new weapons. We make daily attacks. If we manage to occupy twenty metres in the morning, the Russians will push us back in the evening.’ In another letter, a German lance corporal informs his mother: ‘You will have to wait a long time for a special message that Stalingrad is ours. The Russians are not going to give up – they are fighting to the last man.’

By mid-November, the advance of the German troops had been stopped all over the front. The enemy was finally forced to go on the defensive. This was the end of the strategic defensive operation of the Battle of Stalingrad. The troops of the Stalingrad, South-Eastern and Don Fronts fulfilled their tasks, holding back the powerful offensive of the enemy in the Stalingrad direction, creating the prerequisites for a counteroffensive.

During the defensive battles the Wehrmacht suffered huge losses. In the fight for Stalingrad the enemy lost about 700,000 in killed and wounded, over 2,000 guns and mortars, over 1,000 tanks and assault guns, and over 1,400 combat and transport aircraft. Instead of a non-stop advance towards the Volga, the enemy troops were drawn into protracted, exhausting battles in the Stalingrad region. The plan of the German High Command for the summer of 1942 was frustrated. At the same time, the Soviet troops also suffered heavy losses in personnel – 644,000 people, of which 324,000 irretrievable, and 320,000 sanitary. The losses of weapons amounted to about 1,400 tanks, over 12,000 guns and mortars and over 2,000 aircraft.

On 14 October 1942, the Wehrmacht High Command decided to switch to strategic defence on the entire Soviet-German front with the task of holding the lines reached at all costs and creating the prerequisites to continue the offensive in 1943. In Operations Order no. 1, instructing the troops to switch to strategic defence, Hitler, in fact, admitted the failure of the summer offensive in the east!

The Stalingrad strategic defensive operation prepared the ground for the Red Army to launch a decisive counteroffensive with the aim of defeating the enemy near Stalingrad. In this situation the Soviet Supreme High Command concluded that it was on the southern wing of the Soviet-German front, in the autumn of 1942, that the most favourable conditions were created for conducting offensive operations.

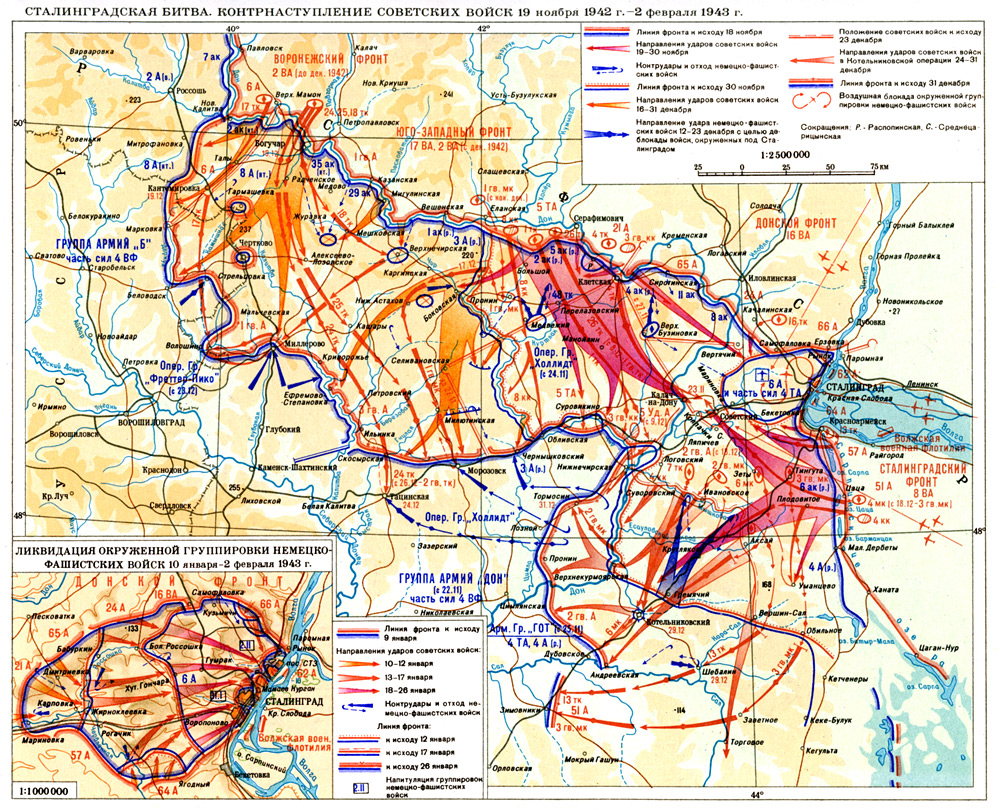

The counter-offensive of the Soviet troops near Stalingrad (19 November 1942 – 2 February 1943)

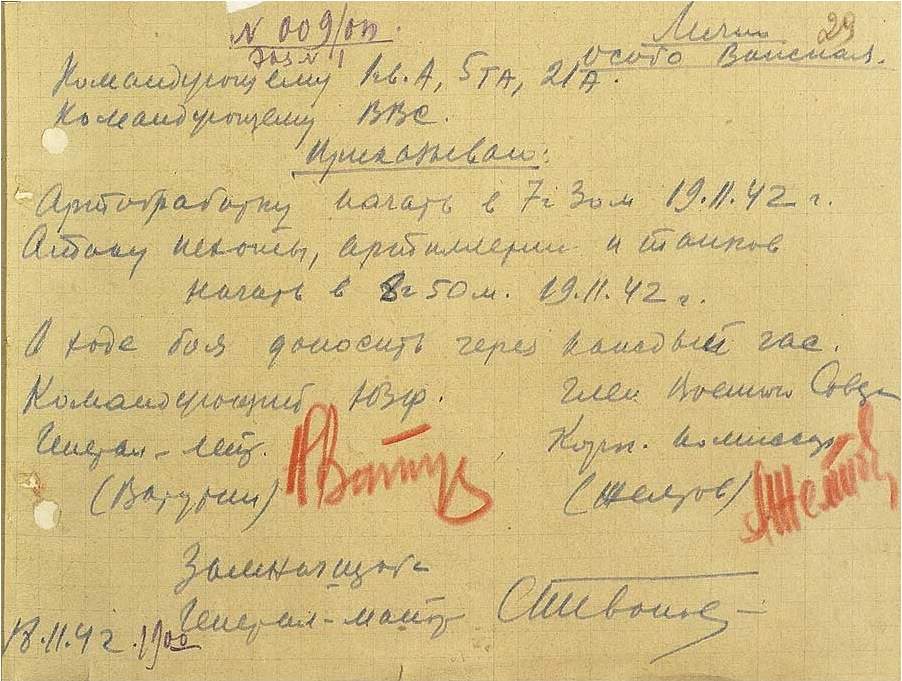

The strategic offensive operation (the counter-offensive near Stalingrad) was carried out under the code name Operation Uranus from 19 November 1942 to 2 February 1943 by the troops of the Southwestern Front, Don Front, Stalingrad Front and the left wing of the Voronezh Front with the participation of the Volga Military Flotilla. Its plan was to defeat the troops defending the flanks of the enemy strike force, by attacking from the bridgeheads on the Don (on the Serafimovich and Kletskaya sectors) and from the Sarpinsky Lakes area (to the south of Stalingrad), and, developing the offensive in converging directions toward Kalach-on-Don and Sovetsky, to encircle and destroy main enemy forces directly at Stalingrad. The development of the counter-offensive plan was led by Army General G. K. Zhukov and Colonel-General A. M. Vasilevsky.

In a relatively short period of time (from 1 October to 18 November), four tank, two mechanised and two cavalry corps, 17 separate tank brigades and regiments, 10 rifle divisions and 6 brigades, 230 artillery and mortar regiments were transferred from the General Headquarters reserve for the purpose of strengthening the fronts of the Stalingrad direction. The Soviet troops included about 1,135,000 people, about 15,000 guns and mortars, over 1,500 tanks and self-propelled artillery pieces. The composition of the air forces at the fronts was increased up to 25 aviation divisions, which managed over 1,900 battleplanes. The total number of operating divisions at three fronts reached 75. However, this powerful grouping of the Soviet troops was specific: about 60% of the personnel of the troops were young reinforcements who did not yet have combat experience.

They were opposed by the German 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army, the Romanian 3rd Army and 4th Army of Army Group B, numbering more than 1,011,000 people, about 10,300 guns and mortars, 675 tanks and assault guns, over 1,200 battleplanes. The most combat-ready German formations were concentrated directly near Stalingrad. Their flanks were covered by the Romanian and Italian troops defending on a wide front. The enemy defence on the Middle Don and to the south of Stalingrad did not have sufficient depth. As a result of the concentration of forces and means in the directions of the main attacks of the Southwestern Front and Stalingrad Front, a significant superiority of the Soviet troops over the enemy was established: 2‑2.5 times in people, and 4‑5 times or more in artillery and tanks.

The offensive of the troops of the Southwestern Front (commanded by Lieutenant General, then from 7 December 1942, Colonel General N. F. Vatutin) and the 65th Army of the Don Front began on 19 November after an 80-minute artillery preparation. By the end of the day, the troops of the Southwestern Front achieved the greatest success advancing 25–35 km: they broke through the defences of the Romanian 3rd Army in two sectors: southwest of Serafimovich and on the Kletskaya sector. The Romanian 2nd and 4th Army corps were defeated, and their remnants together with the 5th Army corps located in the Raspopinskaya area, were flanked. Formations of the 65th Army (commanded by Lieutenant General P. I. Batov), having met fierce resistance, advanced 3–5 km by the end of the day, but could not completely break through the enemy’s first line of defence.

On 20 November, the troops of the Stalingrad Front went on the offensive. “The Katyushas launched the attack,” Colonel General A. I. Yeryomenko wrote. “After that artillery and mortars joined them. It is difficult to convey in words the feelings that you experience while listening to the many-voiced choir before the start of the offensive, but the main thing in them is pride in the power of your motherland and faith in victory. It was just yesterday that we clenched our teeth tightly and said to ourselves: “Not a step back!”, but today our motherland ordered us to go forward…” During the first day, the rifle divisions broke through the defences of the Romanian 4th Army and wedged 20–30 km into the enemy defence line toward the southwest.

It became known at Hitler’s headquarters about the breakthrough in the defence to the north and south of Stalingrad and the defeat of the Romanian troops on both flanks. But there were practically no reserves in Army Group B. It was necessary to withdraw divisions from other sectors of the front. The Soviet troops stubbornly continued to advance, more and more covering Paulus’s grouping from the southwest.

In 2 days of fighting, the troops of the fronts inflicted a heavy defeat on the Romanian 3rd Army and 4th Army. On 21 November, the 26th and 4th Tank Corps of the Southwestern Front reached the Manoilin sector and, turning east, rushed along the shortest path to the Don, to the Kalach area. The 26th Tank Corps, having captured the bridge across the Don, occupied Kalach on 22 November. The mobile formations of the Stalingrad Front advanced towards the mobile formations of the Southwestern Front.

On 23 November, units of the 26th Tank Corps quickly reached Sovetsky and connected with the formations of the 4th Mechanised Corps. The mobile formations of the Southwestern Front and Stalingrad Front, having reached the Kalach, Sovetsky, Marinovka areas, completed the encirclement of the German troops. The cauldron contained 22 divisions and more than 160 separate units that were part of the 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army, with a total strength of about 300,000 people. There has never been such an encirclement of the German troops during the entire period of World War II.

November 1942–2 February 1943)

On the same day, the Raspopinskaya enemy group capitulated. That was the first capitulation of a large enemy group to the Soviet troops in the Great Patriotic War. In total, over 27,000 soldiers and officers of two Romanian corps were taken prisoner near the village of Raspopinskaya.

Here is how an officer of the reconnaissance department of the German army corps assessed the emerging situation at that time: “Stunned and confused, we did not take our eyes off our staff maps – bold red lines and arrows applied to them indicated the directions of numerous enemy attacks, their detour maneuvers, breakthrough areas. With all our forebodings, we did not even in our thoughts allow the possibility of such a monstrous catastrophe!”

On 30 November, the operation to encircle and block the German group was completed. As a result of the rapid offensive of tank, cavalry and rifle formations, the Soviet troops created two fronts of encirclement– external and internal. The total length of the outer front of encirclement was about 450 km. The maximum distance between the outer and inner fronts of encirclement on the Southwestern Front reached 100 km, and on the Stalingrad Front it was between 20 and 80 km. After 12 days of the operation, the depth of advance of the Soviet troops ranged from 40 to 120 km, with an average advance rate of 6 to 20 km per day for rifle formations and up to 35 km per day for mobile groups. However, it was not possible to immediately dissect the German troops encircled by the cauldron. One of the reasons for that included an error in estimating the size of the encircled enemy group which was 80,000 to 90,000 people. Accordingly, data on its weapons were also underestimated.

The High Command of the Wehrmacht made an attempt to rescue the formations and units that were surrounded. A special operation which received the code name Operation Winter Thunderstorm, was planned to release them. For its implementation, a special Army Group Don was created, which included up to 30 divisions. The general management of the operation was entrusted to General Field Marshal E. von Manstein, and its direct leadership and implementation were assigned to Colonel General G. Goth.

On the morning of 12 December, the implementation of Operation Winter Thunderstorm began. With a powerful blow from the Kotelnikovsky area (Kotelnikovo town), the enemy managed to break through the defences of the Soviet troops and advance 25 km by the end of the day. Exceptionally fierce battles unfolded with the use of a large number of tanks. The onslaught of the German troops continued with increasing force and with the active support of aviation. By the end of 19 December, General Goth’s tanks had only 35‑40 km to reach the encircled grouping. Radio messages were already aired to the 6th Army headquarters: “Hold on, the liberation is near!”, “Hold on, we will come!”. Manstein reached Hitler with a request to allow Paulus to make a breakthrough towards Goth’s group. But Hitler set a condition: “Stalingrad must be retained!” In a response radiogram, Paulus reported that his army was not able to solve two tasks at the same time.

On the way of the German Panzer divisions, the 2nd Guards Army (commanded by Lieutenant General R. Ya. Malinovsky), urgently advanced from the reserve of the Supreme High Command General Headquarters, became an insurmountable obstacle. It was a powerful combined-arms unit fully equipped with personnel and weapons (122,000 people, 2,000 guns and mortars, 470 tanks). In a fierce battle that unfolded on the banks of the Myshkova River on 20–23 December, the enemy suffered heavy losses and completely exhausted their offensive capabilities. By the end of 23 December, the enemy was forced to go on the defensive.

At the same time, following the decision of the Supreme High Command General Headquarters, from 25 November to 20 December, the troops of the Western Front (commanded by Colonel General I. S. Konev) and Kalinin Front (commanded by Colonel General M. A. Purkayev) carried out an offensive operation under the code name Operation Mars. Despite the fact that the Soviet troops failed to defeat the main forces of the German 9th Army (commanded by Colonel-General W. Model) after counter attacks from the west and east and eliminate the Rzhev ledge, they blocked up to 30 enemy divisions with active offensive actions, not allowing the German command to transfer the troops from this sector of the front to Stalingrad, where the main events unfolded at that time. Moreover, the enemy was forced to send four more tank and one motorised divisions here from the reserves of their High Command and Army Group Centre.

After the encirclement of the German troops near Stalingrad, the Supreme High Command General Headquarters decided, simultaneously with the liquidation of the encircled grouping, to conduct an operation on the Middle Don (the code name Operation Saturn) in order to defeat the main forces of the Italian 8th Army, Army Group Hollidt, the remnants of the Romanian 3rd Army, and to develop a counter-offensive in the Stalingrad-Rostov direction. However, the German offensive that began on 12 December from the Kotelnikovsky area in order to release the 6th Army forced the Supreme High Command General Headquarters to adjust the plan. Instead of an offensive to the south, the main blow was now directed to the southeast towards Nizhny Astakhov with access to Morozovsk (Operation Little Saturn), with the aim of defeating the Italian 8th Army and the German-Romanian troops operating at the front from Veshenskaya to Nizhnechirskaya, and exclude the possibility of releasing the German 6th Army with a blow from the west. It was decided to postpone the operation to eliminate the enemy group surrounded near Stalingrad.

During the offensive which began on the morning of 16 December, the Soviet troops broke through the enemy defences in a zone up to 340 km wide in 8 days, advanced 150‑200 km and went to the rear of Army Group Don. On the Middle Don, 72 enemy divisions were defeated. The enemy lost 120,000 people (including 60,500 prisoners). The losses of the Soviet troops were also significant – 95,700 people (20,300 of which were lost irretrievably). But most importantly, the enemy used up the reserves intended for the attack on Stalingrad, and abandoned further attempts to unblock the grouping encircled there, which sealed its fate and led to a radical change in the situation in the Stalingrad-Rostov direction. The defeat of the Italian troops on the Don caused literally a shock in Rome. Relations between Rome and Berlin deteriorated sharply. Italy actually ceased to be Germany’s ally.

By this time, formations and units of the German 6th Army were reliably blocked on the ground and from the air. The total area occupied by them was more than 1,500 square kilometers, length along the perimeter – 174 km, north-south distance – 35 km, west-east distance – 43 km. The outer front was 170–250 km away from the encirclement.

The air blockade organised by the Soviet troops over the encircled German group actually cancelled the delivery of food, ammunition, fuel and other resources to the cauldron. The German troops experienced hardship from the cold (the temperature in late December and January reached 20–30 degrees Celsius below zero) and hunger. Horse meat became a luxury in the soldier’s diet; the Germans hunted dogs, cats, and ravens. Here is how Colonel Dingler describes the disasters of the 6th Army: “…Until Christmas 1942 (26 December), the troops were given 100 grams of bread per person per day, and after Christmas this ration was reduced to 50 grams. Later, even these 50 grams of bread were received only by those units that directly fought; in the headquarters, from the regiment and above, they did not give out bread at all. The rest ate a liquid soup, which they tried to make stronger by boiling horse bones.”

German historian F. Mellenthin gives a description of the death of the 6th Army in his book Panzer Battles 1939-1945: “The Sixth Army was doomed, and now nothing could save Paulus. Even if, by some miracle, Hitler had been able to agree to an attempt to break out of the encirclement, the exhausted and half-starved troops would not have been able to break the Russian circle, they would not have had vehicles to retreat to Rostov along the ice-crusted steppe. The army would have died during the march, like the soldiers of Napoleon during the retreat from Moscow to the Berezina River.”

Despite the catastrophic situation of the 6th Army, its commander continued to fulfill the Fuhrer’s categorical demands. “The fact that we will not leave here must become a fanatical principle,” Hitler said. In order No. 2 of 28 December 1942, when it was already clear that the Wehrmacht had no strength to liberate the encircled grouping in Stalingrad, he stated: “…As before, my intention remains to keep the 6th Army in its fortress (in Stalingrad) and predetermine its release.”

The Supreme High Command General Headquarters developed a plan of the operation to eliminate the encircled group, which received the code name Operation Ring. The operation was envisaged in three stages: the first – to cut off and destroy the enemy in the western and northeastern parts of the encirclement area; the second – to destruct the enemy troops at the close approaches to the city; the third – to eliminate the remaining enemy groups in the city. On 4 January 1943, the operation plan was approved by the Supreme High Command General Headquarters.

The liquidation of the encircled enemy was entrusted to the troops of the Don Front (commanded by Lieutenant General, then from 15 January 1943, Colonel General K. K. Rokossovsky). At the beginning of the operation, the troops of the front included 212,000 personnel, 257 tanks, 6,860 guns and mortars, and 300 battleplanes.

The encircled German grouping still retained combat readiness and had the following composition before the start of the operation: 250,000 personnel, 4,130 guns and mortars, 300 tanks and 100 battleplanes. However, the moral, psychological and physical condition of the encircled troops was extremely difficult. Despite the hopelessness of the situation, Berlin continued to send telegrams calling to “Stand to the end!”

On 8 January, the command of the Don Front issued an ultimatum to the command of the encircled group, demanding that they stop senseless resistance and accept the terms of surrender. The ultimatum signed by the representative of the Supreme High Command General Headquarters N. N. Voronov and the commander of the Don Front K. K. Rokossovsky, was transmitted by radio to the Paulus’s headquarters and delivered by the truce envoys. However, the commander of the German 6th Army rejected the proposal of the Soviet command in writing.

The troops of the Don Front went on the offensive on the morning of 10 January 1943 almost simultaneously from all directions, gradually squeezing the encirclement. With the despair of the doomed, the enemy demonstrated stubborn resistance, repelling the attacks of the Soviet troops. On 21 January, despite the deterioration in the position of the encircled grouping due to the loss of the airfield in the Pitomnik area, through which the enemy mainly supplied their troops, the German command again rejected the offer of surrender.

On 24 January, F. Paulus reported to the Fuhrer’s headquarters by radio (cited in shorthand form): “…On the southern, northern and western fronts, phenomena of degradation of discipline were noted. Unified command and control of the troops is impossible… 18,000 wounded are not getting the most basic medical care… the front has been torn apart… further defence is meaningless. A disaster is inevitable. In order to save the people who are still alive, I ask you to immediately give permission for surrender. Paulus.”

Hitler replied with a short telegram in an irritated manner: “I forbid capitulation! The army must hold its ground to the last man and to the last bullet!”

By the end of 26 January, units of the 21st Army (commanded by Lieutenant General I. M. Chistyakov) allied near the village of Krasny Oktyabr and on Mamayev Kurgan with the units of the 62nd Army advancing from Stalingrad. The enemy was divided into two parts in the city – the southern group (the remnants of nine divisions) led by F. Paulus and the northern group (the remnants of twelve divisions) in the area of the Tractor Plant and the Barrikady Gun factory.

On 28 January, the enemy’s southern group was divided into two more parts. Now three isolated groups had formed in Stalingrad, which continued to wage a hopeless struggle. On the night of 31 January, the chief of staff of the 6th Army, Lieutenant General A. Schmidt, entered Paulus’s room, which was located in the basement of a department store, and handed him a sheet of paper with the words: “Congratulations on your promotion to the general field marshal position.” It was the last radiogram from Hitler received in the “cauldron”. On 31 January, the southern group was forced to stop their senseless resistance. On the same day, the commander of the 6th Army along with the generals and staff officers also surrendered.

The northern group of the 6th Army commanded by General of the Infantry K. Strecker, continued their senseless bloody resistance. Hitler’s headquarters transmitted the following order to this group: fight to the last bullet, die, but do not surrender. The Soviet command decided to inflict a powerful fire strike on this group. Up to 1,000 guns and mortars were concentrated on a 6-kilometer section. On 1 February, massive fire hit the enemy position.

The 65th Army commander, Lieutenant General P. I. Batov, wrote in his memoirs about it: “…And now all this power rumbled. After 3‑5 minutes, the Nazis began to jump out and creep out from the dugouts, cellars, from under the tanks. Some fled, others knelt down, mad, raised their hands to the sky. Some threw themselves back into cover and hid among pillars of smoke and jumped out again…” At the same time, aviation massively bombed the enemy. German soldiers and officers surrendered in droves, throwing down their weapons.

On 2 February, the northern group of enemy forces capitulated. Over 40,000 German soldiers and officers under the command of General K. Strecker laid down their arms. The fighting on the banks of the Volga River ceased. During the liquidation of the encircled German grouping (from 10 January to 2 February 1943) the troops of the Don Front defeated 22 divisions and 149 reinforcement and service units. 91,000 people were taken prisoner, including 2,500 officers and 24 generals. On the battlefield, after the liquidation of the encircled grouping, about 140,000 enemy personnel were picked up and buried.

In his report to the Supreme Commander I. V. Stalin, the representative of the Supreme High Command General Headquarters, Marshal of Artillery N. N. Voronov and the commander of the Don Front, Colonel-General K. K. Rokossovsky, reported: “Fulfilling your order, at 16:00 on 2 February 1943 the troops of the Don Front completed the defeat and destruction of the enemy’s Stalingrad grouping.

Due to the total liquidation of the encircled enemy troops, the fighting in the city of Stalingrad and near Stalingrad ceased.”

The turning point in the entire Second World War

The Battle of Stalingrad ended with a brilliant victory for the Soviet Armed Forces. It marked the beginning of a radical change not only in the course of the Great Patriotic War, but in the Second World War as a whole. During the Battle, the fascist bloc lost a fourth of its forces operating on the Soviet-German front. The German 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army, the Romanian 3rd, 4th and Italian 8th armies were defeated. The total losses of the enemy amounted to about 1,500,000 people in killed, wounded, captured and missing, due to which, for the first time during the war, national mourning was declared in Germany. The losses of the Red Army amounted to about 1,130,000 people (of which about 480,000 were irretrievable). The strategic initiative firmly and definitively passed into the hands of the Soviet Supreme High Command, and conditions were created for the deployment of the Red Army’s general offensive and the mass expulsion of the invaders from the occupied territory of the USSR. The victory at Stalingrad raised the international prestige of the Soviet Union and its Armed Forces and strengthened the anti-Hitler coalition.

The defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad was a moral and political shock for the whole of Germany, shook its foreign policy positions, and undermined the confidence of the satellites: Japan was convinced of the inexpediency of starting hostilities against the USSR, while Turkey, despite Germany’s pressure, sought to maintain neutrality.

German authors, who usually covered the events on the Soviet-German front in a tendentious manner, were forced to admit the real defeat of Germany. General S. Westphal wrote: “The defeat at Stalingrad horrified both the German people and their army. Never before the entire history of Germany saw such a terrible loss of so many troops.” The German historian W. Görlitz emphasised in his book History of the Second World War: “The catastrophe at Stalingrad was a great turning point not only in the domestic policy sense, but also in the foreign policy sense. It resulted in a severe shock to the entire sphere of German domination in Europe.”

The victory in the Battle of Stalingrad showed the increased capabilities of the Red Army and Soviet military art. In the Battle of Stalingrad, the strategic defensive and offensive operations of groups of the fronts were organically interconnected, culminating in the encirclement and destruction of the large enemy grouping. The victory at Stalingrad was the result of the unbending fortitude, courage and mass heroism of the Soviet forces. For military distinctions demonstrated during the Battle of Stalingrad, 44 formations and units were awarded the honorary names of Stalingrad, Abganer, Don, Basargin, Voropon, Zimovnikov, Kantemirov, Kotelnikov, Srednedon, Tatsin; 55 were awarded orders, 183 were converted into guards. Tens of thousands of soldiers and officers were awarded government awards. 112 most distinguished soldiers became Heroes of the Soviet Union.

On the 20th anniversary of the Victory in the Great Patriotic War, the Hero City Volgograd was awarded the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star medal. In order to perpetuate the victory at Stalingrad, the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated 22 December 1942, even before the end of the battle, established the medal for the Defense of Stalingrad, which was awarded to more than 700,000 participants in the battle.

The victory of the Red Army at Stalingrad caused a huge political and labor upsurge of the entire Soviet people. It instilled faith in the speedy liberation of the territory of the USSR from fascism, strengthened the morale of the soldiers at the front, and directed the home front workers to further intensify the fight against the enemy and provide the front with everything necessary.

In accordance with the Federal Law No. 32-FZ of 13 March 1995 “On the Days of Military Glory and Memorable Dates of Russia”, 2 February 1943 is celebrated as the day of military glory of Russia – the Day of the defeat of the German Nazi troops by the Soviet forces in the Battle of Stalingrad.