Rodney Phillips, Sarah Funke, The New York Public Library

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov was born on April 23, 1899, into, as he put it, the “great classless intelligentsia” of St. Petersburg. His father, Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (Nabokov), a titled aristocrat, was a leader among liberal politicians and advocated democratic principles as a statesman and journalist. His mother, Elena Ivanovna Rukavishnikov, was a cultured and intellectual heiress. Educated at home by tutors and governesses, young Nabokov was fluent in Russian, English and French by the age of 7. When he entered school at 11, he had already read all of Shakespeare in English, all of Tolstoy in Russian and all of Flaubert in French.

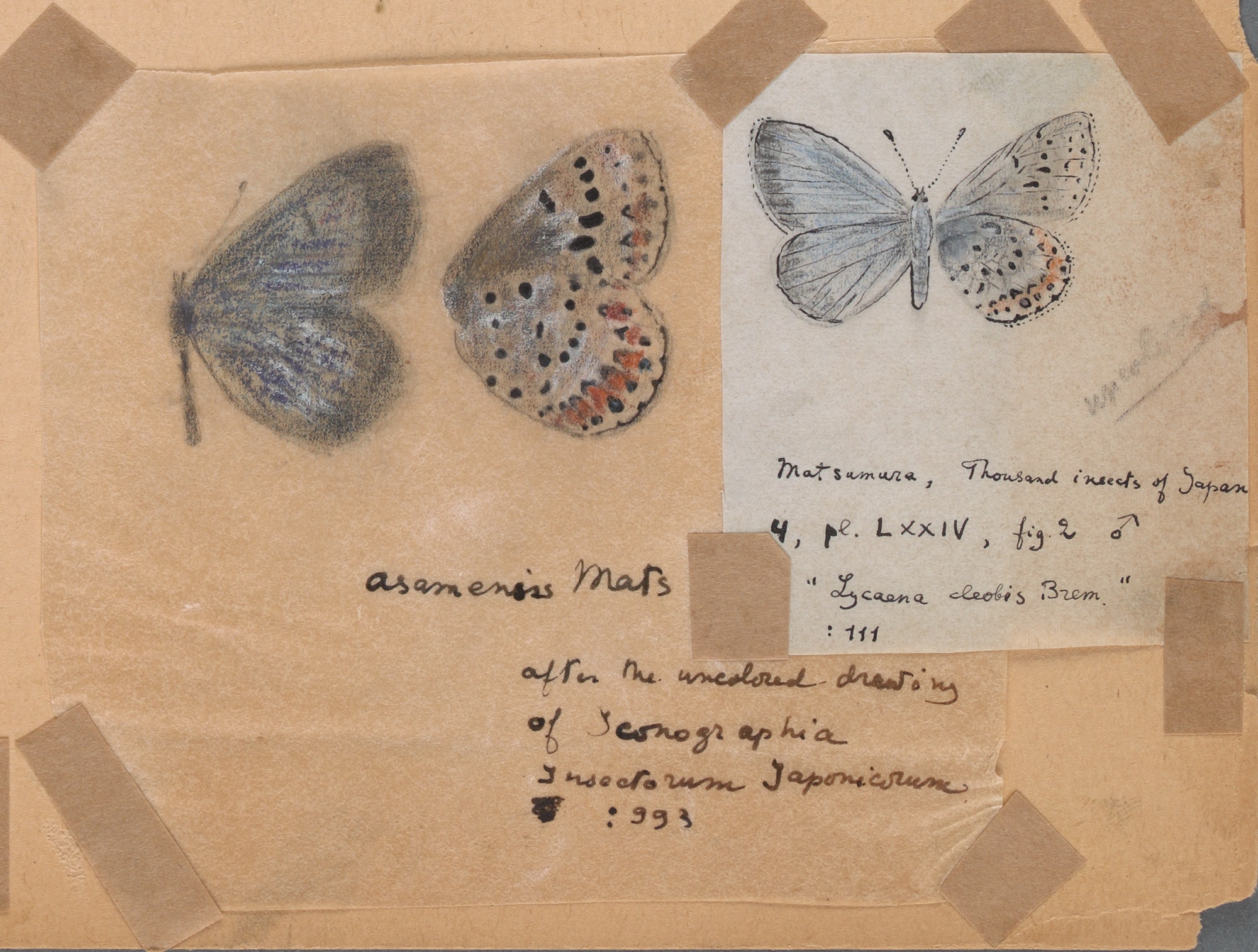

His early youth was divided between St. Petersburg, European coastal resorts (mainly the Riviera and Biarritz) and Vyra, his beloved summer haunt on his parents’ country estate, which he lovingly preserved in several of his novels and in Speak, Memory, the autobiography he published in three versions over the course of 15 years. In all these locales he engaged in the pursuits that permeate his fiction and memoirs: hunting butterflies, falling in love and writing poems.

Early writings

By the time he was 15, Nabokov was writing poetry prolifically. His first publication, documented only by his recollection of it, was a single poem he prepared for distribution to friends and family in 1914. In 1916 he inherited his own fortune (roughly $2 million today) and the grandest of several manors on the family estate. He then paid for the publication of Stikhi (Poems), a collection of 68 love poems. Over the next several years he averaged nearly one poem every other day. The earliest wave was preserved by his mother in marbled notebooks; later, Nabokov kept his own composition journals. His first major collections, Grozd’ (The cluster) and Gorniy Put’ (The empyrean path), both published in 1923, were culled from these sources.

Nabokov, fearing that his two oldest sons – Vladimir, 18, and Sergei, 17 – would be drafted into the Red Army, sent them from St. Petersburg to the Crimea just after the Bolshevik coup in the fall of 1917. They were soon joined at Gaspra, on the estate of Countess Sofia Panin, by the rest of the family.

Between June 1916 and February 1918, he completed 334 poems, of which he planned to publish two-thirds before leaving the Crimea. That proposed volume was never produced, but a selection was printed in 1918 in the Crimea in Dva puti (Two paths), a collection he assembled with a schoolmate.

The beginnings of émigré life

When the Crimea was evacuated in the spring of 1919, the Nabokovs took a circuitous route to London; in the fall, Vladimir and Sergei left for their first term at Cambridge University. A notebook from those months in London contains a chess problem for nearly every poem, revealing the foundation of what would become another of Nabokov’s lifelong passions.

At Trinity College, Cambridge, Nabokov began his studies in zoology. Though he continued his lepidopterological pursuits unofficially and published his first entomological paper there – on Crimean lepidoptera – he soon switched his official field of concentration to modern and medieval languages. He focused his studies on Russian and French, presumably to allow himself more time to pursue his own writing. To that end he bought Vladimir Dahl’s formidable four-volume Interpretative Dictionary of the Living Russian Language, and committed himself to reading 10 pages a day.

In August 1920, the Nabokov family moved to Berlin, where Vladimir would compose all eight of his Russian novels. London had proved much too expensive, and the Berlin economy was attracting Russian émigrés by the tens of thousands. Nabokov helped to negotiate the birth of a formidable émigré publishing house, Slovo, with the assistance of Ullstein, one of Berlin’s largest German presses. He also co-edited Rul’, a popular Russian-language daily with a worldwide circulation. From Cambridge, Vladimir began to publish poems, chess problems and even crossword puzzles in Rul’, usually under the pen name “Sirin,” to distinguish his work from his father’s. By the fall of 1921, the Nabokov home had become a cultural center, hosting evening gatherings frequented by well-known émigré artists, writers and musicians.

By 1920, when he completed his first year at Cambridge, Nabokov had been translating into and out of Russian for years: when he was 11, he reincarnated Mayne Reid’s The Headless Horseman as French poetry; at 17, he brought Alfred de Musset’s La Nuit d e décembre into Russian; and at Cambridge, translations among his languages of choice were required. When, in June 1920, he and his father discussed the challenges that Romain Rolland’s novel Colas Breugnon would pose for a translator, he took up the gauntlet himself; Nikolka Persic (Nikolka the Peach) was published by Slovo in November 1922. The same service for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, published four months later as Ania v strane chudes, required substantially less effort, and the result is still considered one of the best versions extant in any language.

On May 8, 1923, Nabokov met Véra Evseevna Slonim at a masquerade ball in Berlin. Working in her father’s small publishing concern, with literary aspirations of her own, Véra was already familiar with some of Nabokov’s writing. He spent that summer on a farm in the south of France, in an attempt to work through his grief at the loss of both his father and his fiancée (he had written many poems to Svetlana Siewert, and her parents had broken off the young couple’s engagement that January). That summer Véra read “The Encounter,” a poem Nabokov composed about their meeting and submitted to Rul’ from France. When he returned to Berlin in the fall, he began to court Véra.

Inflation in Berlin had begun to drive the émigré community to other centers of activity, primarily Paris, and that fall Nabokov’s mother moved to Prague with his favorite sister, Elena. He visited them twice during the following year, which he spent writing – stories, scenarios and sketches – although this did not prove lucrative enough to allow him to support himself, his mother and sister, and his new wife-to-be. On April 15, 1925, he married Véra, and the need for money became even more pressing and persistent. Nabokov managed to spare enough time from his writing to make a living as a tutor – in French, English, Russian, prosody, tennis and boxing – and regularly published reviews in Rul’, while Véra did secretarial work.

Nabokov remained an émigré writer, living and publishing in Europe and the United States. By 1925, he had laid the groundwork for his future careers as a writer, a teacher and a translator. The passions he developed early on would drive his literature, and his talent for languages would sustain him financially as well as bring him critical acclaim.

Major English-language literary works

Though he was a prolific Russian émigré writer in Europe, by the fall of 1938 Vladimir Nabokov’s financial resources were depleted. He solicited a grant from the Russian Literary Fund in the United States, claiming: “My material situation has never been so terrible, so desperate.” He received $20. Unable to get a French work permit, he cast about for academic and literary opportunities in England and America. Sharing a studio apartment in Paris with his wife, Véra, and his son, Dmitri, he composed his first novel in English, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, on a makeshift desk consisting of his suitcase placed over the bidet.

The following year, a fellow émigré poet and editor passed on an offer for a summer lectureship at Stanford University, in California. Nabokov seized the opportunity and immediately began composing lectures on Russian literature. He also wrote his first story in English, never published in his lifetime: “The Enchanter,” a clear precursor to Lolita. In May 1940, he, Véra and Dmitri boarded the Champlain for the United States, an episode that is poignantly described in his memoir. He brought with him his lecture notes and the manuscript of Sebastian Knight.

James Laughlin, the young heir to a steel fortune and the head of the new publishing house New Directions, contacted Nabokov at the start of 1941, looking for publishable material. Nabokov responded with The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, in which the Russian émigré narrator, V., is on the trail of his half brother, the writer Sebastian Knight. Laughlin accepted the novel and commissioned Russian translations and studies from Nabokov, and ultimately brought out Nikolai Gogol (1944), Three Russian Poets (1945) and Nine Stories (1947) before Nabokov left New Directions for more lucrative opportunities elsewhere. In 1954, Laughlin was among the American publishers that rejected Lolita, but in 1959 he capitalized on Lolita’s success by reprinting Sebastian Knight.

Bend Sinister, the first novel Nabokov composed in the United States, is his most overtly anti-Fascist, anti-Communist novel. He had envisioned it as early as 1942, with the title The Person From Porlock, later Game to Gunm[etal], and still later as Solus Rex, or possibly Vortex. He described it in broad strokes to friends in May 1946: “I propose to portray in this book certain subtle achievements of the mind in modern times against a dull-red background of nightmare oppression and persecution. The scholar, the poet, the scientist and the child – these are the victims and witnesses of a world that goes wrong in spite of its being graced with scholars, poets, scientists and children.”

American journals, primarily The New Yorker, and ultimately collected them as Conclusive Evidence in 1951. They covered the years between his “awakening of consciousness,” in August 1903, at the age of 4, and a parallel dawning in his son and future translator, Dmitri, as his family left for the United States, in May 1940.

In the summer of 1953, he decided to translate Conclusive Evidence into a Russian “version and recomposition,” and he sought Véra’s help, lest another, less able contender make an attempt. The result, Drugie berega (Other shores), was published in New York by Chekhov House in 1954. Though his books were officially banned in the Soviet Union, he had a reasonably large audience among émigrés in the United States and in Europe.

Aesthetic bliss: Lolita (1955)

In 1953, having nearly completed Lolita, his “enormous, mysterious, heartbreaking novel,” after “five years of monstrous misgivings and diabolical labors,” Nabokov declared that it “has had no precedent in literature.” He embarked on the quest for an American publisher, telling each of five houses – Viking, Simon & Schuster, New Directions, Farrar Straus, and Doubleday – to use the utmost discretion in allowing the manuscript to leave their desks. No one would publish it. The Partisan Review agreed to print a portion of it, but only on the condition that Nabokov sign the work. Fearing that he’d be identified with his protagonist, he wrote in a December 23, 1953, note to Katharine White, “its subject is such that V., as a college teacher, cannot very well publish it under his real name.”

Lolita received no public attention until after it was banned in France, along with many other Olympia Press titles, under pressure from the British Home Office, and Graham Greene included it in a year-end list of the three best novels of 1955. Greene helped shepherd the first British edition into print, writing to Nabokov that “in England one may go to prison, but there couldn’t be a better cause!”

Final novel: Look at the Harlequins! (1974)

Still largely overlooked in critical circles, Look at the Harlequins! – Nabokov’s last published novel – recounts the autobiography of Vadim Vadimych N., whose life and work seem to parody the biography that a wayward scholar might create of Nabokov himself. (He wrote in 1973 of the research by Andrew Field, one of his biographers: “It was not worth living a far from negligible life only to have a blundering ass reinvent it.”) This also recalls a lecture, “Pushkin, or the Real and the Plausible,” that Nabokov delivered in 1937 on the evils of “fictionalized biographies.”

Reviews of Look at the Harlequins! were mixed; readers who had been put off or dismayed by Ada and Transparent Things were charmed by this readable tale, but to those who saw the merits of Nabokov’s previous two novels it seemed weak.

Despite such criticism, Look at the Harlequins! was nominated for the National Book Award, but it did not win. Perhaps most interestingly, Look at the Harlequins! contains a realistic return to Russia that Nabokov never undertook. Though he was opposed to visiting countries where totalitarianism dominated, Nabokov gleaned information from friends and family who had returned to Russia and adapted their details into Vadim Vadimych’s homecoming, just as James Joyce had pumped relations in Dublin for some of the local color that appears in Ulysses.

Nabokov died in 1977, never having returned to Russia.