At the beginning of the 20th century, the whole world learned about the existence of such a phenomenon as the Russian Icon

By Oksana Kopenkina, art analyst and founder of the Russian-language Arts Diary website

Henri Matisse, visiting an exhibition of early masters in the Tretyakov Gallery in October 1911, said: “Russians have no idea what artistic wealth they own. Everywhere the same brightness and manifestation of great power of feeling. Your young artists have here, at home, incomparably better examples of art than abroad…”

Angel with Golden Hair

The Angel with Golden Hair was once part of the Deesis order. This is a group of several icons. In the middle was Christ the Almighty. And on the left and right – icons with the Mother of God, John the Baptist and other angels and saints. They seem to ask the Son of God to forgive parishioner’s sins. The “Angel” was among such intercessors.

With the help of the assist technique, his head is covered with thin strips of gold leaf. Unfortunately, the icon has come down to us in a modified form. After all, the surface was always covered with varnish, which darkened strongly after 100 years. And the artists of the new era have revamped the icon. No, they did not restore, but painted the same image over a dark layer. But they often added features of the new era.

Therefore, the golden background of the Angel in the 17th century was changed to green. The color and outline of his robe has also been changed. But the image itself remained almost the same.

The Russian master took the canonical Byzantine image of the Angel as a basis. It seems that the images are very similar. Nevertheless, we see some peculiarities in the Russian icon. The master enlarged and lengthened the eyes, lowering their outer corners down. The result was sad and kind eyes.

He also added shadows to the corners of the lips. The illusion of a light smile occurred.

And this combination of sad eyes and a smile creates an incredible feeling of light, joyful sadness. These are the eyes of a loving, sympathetic and asking creature for you.

The Russian master does not just repeat the image. He does everything to show the extra-terrestrial nature of the Angel. His boundless love and willingness to ask for us forever.

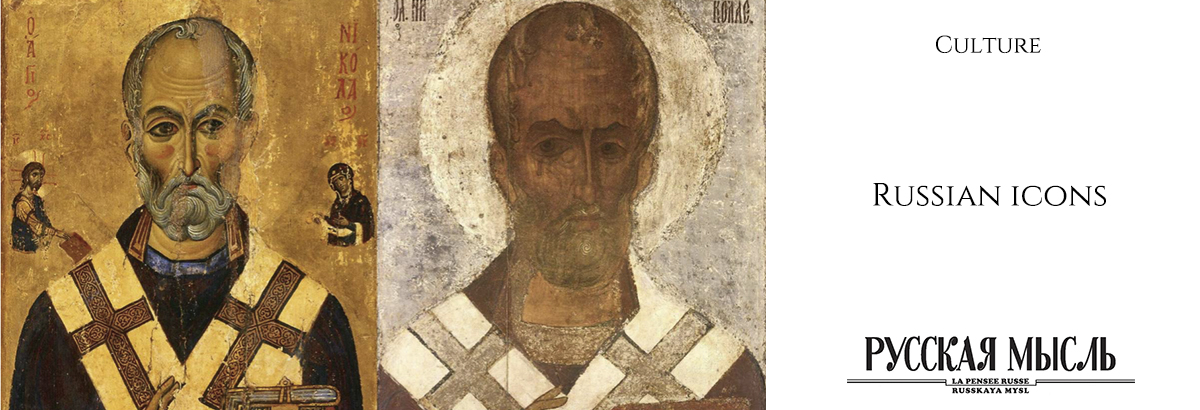

Nicholas the Wonderworker. XIII century

The icon depicts one of the most famous saints: the patron saint of sailors, the pacifier of the warring and the savior from a vain death. He blesses with one hand and holds the Gospel in the other.

The Russian master again took the Byzantine canon. But it added something special. This is easy to see when comparing the two icons.

The Novgorod artist lengthened and widened the skull, made the fingers thinner. And the nose as well. All this visually endowed the saint with even greater intelligence and kindness. But most importantly, the illusion of movement is noticeable in the face of St. Nicholas: crooked eyebrows, a curl in the beard, asymmetrical eyes.

By the way, about the eyes. Pay attention to how the eyes of the saint are different!

Initially, this technique was taken from the Byzantines. They, in turn, applied the ancient heritage. Even the ancient Greeks noticed how the image comes to life if you add a little asymmetry to the face. We know this thanks to the surviving Fayum portraits.

But the Russian master used this technique especially freely. And the eyes not only make them different in size, but also places one above the other.

The Russian master created a unique image of a very wise person with lively eyes. They are filled with an understanding of something beyond, inaccessible to an ordinary person.

Don’s Icon of the Mother of God. XIV century

The Mother of God holds the baby Christ in her arms. They press their cheeks against each other. Therefore, this type of icon is called Eleusa, which means “Tenderness”.

This type of icons came to Russia almost immediately after Christianity became the main religion. The first was the Vladimir’s Mother of God. All subsequent icons of Eleusa were created in its image and likeness.

It seems that the Russian master worked according to the Byzantine canons. But he added some unique features. Jesus’ legs are bare to the knees. And his ring finger is bent. All this gives him the features of a real child, not a small adult.

But the main uniqueness of this icon is different. The Byzantine masters depicted the Mother of God primarily saddened. After all, she already knew about the fate of her son. These eyes are not looking at the child, but somewhere to the side. As if Saint Mary is thinking about the future.

The Russian master makes changes: he again enlarged the eyes, enhanced their asymmetry. Added micro-wrinkles to the outer corners of the eyes. He also directed the gaze of the Mother of God to the son and lifted the corners of her lips up.

As a result, the feeling is created that her gaze is filled with love, and the sadness recedes. She looks at the child and smiles slightly at him. The master deliberately emphasizes the love of a mother for her son.

We have already noticed that Russian artists strove to create images that radiate kindness and mercy. This does not mean that this was not in the Byzantine icons. But the tendency to increase this effect is obvious.

The fact is that the icon was very important for the Russian Christian. Before her they prayed for everything in the world. Not only in difficult times, but also with minor worries, it was easier to go to a very merciful image. One who understands everything and forgives everything. And most importantly, she will accept any prayer, even the most mundane. The artists intuitively understood this and created for their main viewer, the believer, what he so desired.

Andrey Rublev. The Holy Trinity. XV century

Three Angels sit around a table with only one bowl. Behind the angels, a rock, a tree and a building rise.

This canonical image based on the Old Testament plot “The Hospitality of Abraham”. Abraham and his wife Sarah met three strangers, beautiful youths. We invited them into the house and treated them in their garden. And they also sacrificed a calf for them.

Before the 15th century, craftsmen painted details from this plot. At least, they depicted Abraham and Sarah next to the main heroes. But Rublev made significant changes. Let’s compare his “Trinity” with a Byzantine icon.

Rublev removed depiction of Abraham and Sarah. All the dishes from the table were removed as well. Except for one bowl with the head of the sacrificed calf. Thus, he focused all attention on the three Angels. And now the “Hospitality of Abraham” turns into an attempt to depict the Trinity of God.

The Byzantine master’s angels are also very similar. He also was trying by this to show that God the Father, God the Son and the Holy Spirit are inseparable from each other. But Rublev combined three shapes in a circular composition. The single bowl symbolizes the unity. After all, it is one for all!

Rublev deliberately does not explicitly indicate who is who. After all, the trinity of God cannot be known to either man or even an angel.

But we will try anyway…

The angel in the middle offers a bowl to the one on the left (for the viewer). He seems to say: “Take this cup, take the role of the sacrificial calf, and I bless you for this.” We see him leaning towards him and blessing the cup. The tree behind him also bent towards him, as a symbol of birth on Earth.

The right angel has straightened up: he is ready to receive this cup. And the straight columns of the building echo it. He gladly accepts the blessing of His Father, the chief architect of this world. The right angel leaned forward strongly, as if assuring him of his readiness to support.

Rublev portrays a silent dialogue, without words and without fears and doubts inherent in a person. Therefore, there is a feeling of otherness.

All the poses are barely different from each other, but they say a lot. Such a silent and at the same time eloquent image has never been created.

17th – 18th centuries Russian icons

Byzantium fell in the middle of the 15th century. The Russian aristocracy turned gaze to the West. And there they saw the magnificent baroque and incredible realism.

Of course, it amazed them. They wanted secularity and brightness in their life. This was inevitably reflected in the icons. The Virgin appeared a pronounced chiaroscuro, and the flat image became three-dimensional.

The Holy Trinity was filled with many details and decorative ornaments. And the feeling of otherness simply dissolved in it.

The very endless kindness and love, expressed in the language of painting by the masters of the XII-XVI centuries, faded into the background. For the sake of external detailing and even decorativeness.

Rublev’s “Holy Trinity” remained the pinnacle of Russian icon painting. And no one succeeded in creating something like that.