Both Italians and Russians are characterised by a poetic craving for flatness, for the Baroque

VICTOR LOUPAN, Head of the Editorial Board

I think there is no person in the world who would not love Italy. There is no country in the world to have everything as brilliant and versatile as Italy. And so that both the past and the present are organically intertwined to generate a continuous stream of civilisation.

Italian architecture is incomparable, Italian pictorial art is canonical, Italian music is unsurpassed. Modern reality is unthinkable without Italian fashion and Italian design. Italian cuisine may be less sophisticated than the French one, but there is something about its “simplicity without variegation” that makes it unsurpassed.

From my incomplete list, one can draw a not entirely correct conclusion: they say, it is good to relax in Italy enjoying the centuries-old cultural heritage, dressing beautifully and eating deliciously. This is all true. But Italians also manufacture the best and most technologically advanced cars in the world – Lamborghini, Ferrari and Bugatti, which simply have no peers. And for fans of motorcycles and fast driving, MV Agusta and Ducatti are as canonical as Monteverdi or Gesualdo for music lovers.

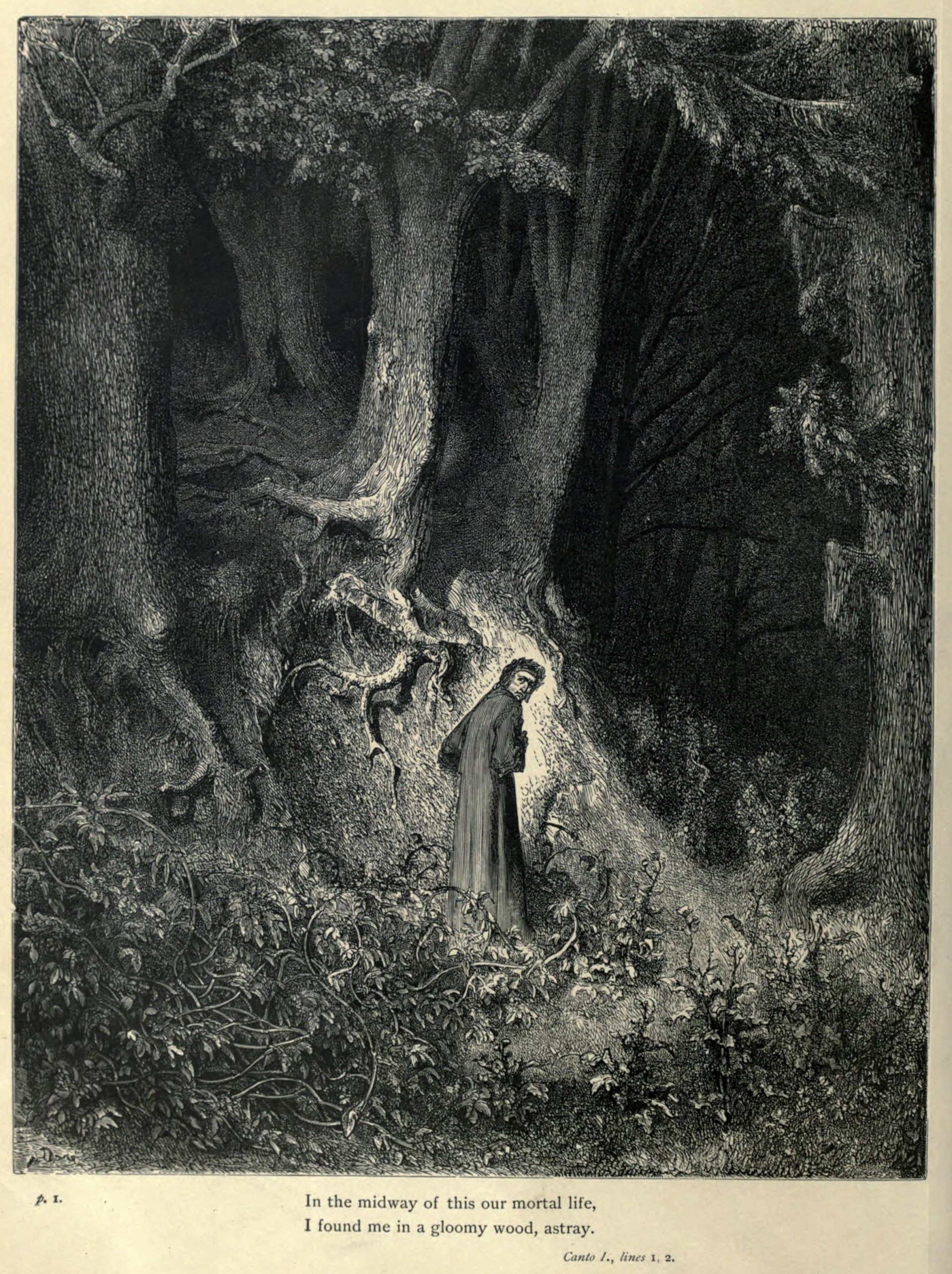

The influence of Italy on world culture is enormous, despite the fact that, unlike English, Spanish, French and even German, Italian is not an international bridge language. But here is the paradox – this year the entire “civilised world”, as they say, is tremblingly celebrating the 700th anniversary of “The Divine Comedy” written by the poet Dante Alighieri. The poem is divided into three parts – “Hell”, “Purgatory” and “Paradise” – each of which consists of 33 cantos, except “Hell” which includes 34 of them to emphasize the disharmony of this terrible place. But the question here is not the analysis of the work or the great merit of Dante, who actually invented the Italian language, but the fact that “The Divine Comedy” is considered the greatest monument of global culture. There is simply no other work in the world that could compare itself to Dante’s masterpiece, although many masterpieces had been written since then. It is just that “The Divine Comedy” goes beyond what is commonly called “literature”. There is something superhuman, mystic in it. As if, without knowing it, the poet’s divine genius opened a tightly closed door and allowed us, for a moment, to look somewhere where it is very scary, but very attractive.

Almost 200 years later, at the very end of the 15th century, the great artist Sandro Botticelli illustrated “The Divine Comedy”. 92 of the initial 100 drawings have survived to us. There is no doubt that they are beautiful, brilliant. But when looking at them with admiration, one involuntarily realises that despite the artist’s genius, the pictures do not reach – and cannot reach – that unthinkable depth that Dante left us, mere mortals. Finished writing, drew a line and died.

Not only Botticelli tried to illustrate “The Divine Comedy”. The great William Blake and Gustave Doré, the best illustrator of the 19th century, took the matter up. But none of them managed to conquer Dante’s miraculous peak.

Moreover, Italian literature as such is incomparable with the great – English, French, German or Russian – literatures. The Italians themselves admit it and explain it through the fact that the Italian language was formed and established itself as a language of culture, quite late. After all, Italians still speak different dialects, sometimes even poorly understanding each other. Despite this, God granted them Dante.

It sometimes seems that Russians and Italians are alike in that “they cannot be understood with the mind”. Bourgeois restraint and bourgeois order are alien to both Russia and Italy. Such kind of it, you know, where everything is tidied up, made comfortable, calm and boring. Both Italians and Russians are characterised by a poetic craving for flatness, for the Baroque.

We often remember how Russian writers, poets and artists loved Italy. How they, arriving there, seemed to arrive in paradise. But we are less often interested in how Italians perceived Russia. As fate willed, I had the opportunity to work with a direct descendant of the architect Pietro Antonio Solari for several years, who, before coming to Russia, participated in the construction of the unsurpassed Milan Cathedral. Upon his arrival in Moscow, where he came with his assistants, Solari completed the construction of the Moscow Kremlin’s Faceted Chamber launched by Marco Ruffo. During his residence in Moscow where he stayed for only three years, Solari designed and built part of the Kremlin walls and towers, including Borovitskaya and Spasskaya Towers. A plaque in Latin still hangs above the Spassky Gate: “Built by Petrus Antonius Solarius”. It came down to us from the times of construction of the tower.

There are few surviving documents about the work of the great Italian architect in Russia. But the family of his descendants kept some letters, excerpts, notes, from which it is believed that, having got to Russia during the times of the Grand Duke of Moscow and Vladimir Ivan III, such a Renaissance man as Solari seemed to be in a wonderland. He was amazed at the scale of construction works. The Moscow Kremlin was, in his opinion, the most powerful fortress in the world at that time. Solari admired the skill of the Russian architects with whom he had the opportunity to work together. He was also surprised by the fact that Moscow was actually a wooden city. He also lived in a wooden house and was interested in the unfamiliar technique of wooden construction. Much in Russia, of course, surprised him, but he apparently fell in love with Russia, because, having returned home, he dreamed of going there again.

Rome”

Remembering the great Italian architects who worked in Russia, we most often turn to the famous figure of Bartolomeo Rastrelli. But he came to Russia with his father at the age of 15 and lived there until his death at the age of 71. So, he was Italian rather formally than really. But the person of Solari is actually unusual.

It is also interesting to note here that Russia almost completely ignored the Renaissance. At the time when such brilliant artists as Giotto, Masaccio, Botticelli, da Vinci, Michelangelo and many others were creating in Florence and other nearby cities, there was no pictorial art in Russia at all. Russia developed icon painting art. Russian historians have preserved the names of three great icon painters of the 14th-15th centuries – Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev and Dionysius. They were genius icon painters, but not “artists” in the European sense of the word.

Many European intellectuals regard the Renaissance as a matrix not only of modernity, but also of “Europeanness”. Therefore, through ignoring it, Russia remained “in the darkness of the Middle Ages” and thus separated itself from Europe. Joseph Brodsky considered this idea delusional, although he did not deny that Russia actually ignored the Renaissance. Perhaps that is why Russians are the most distinctive and unusual among all European cultures, literatures, music schools and art schools. European culture is conceivable without a procession of “European” names, but is absolutely unthinkable without Dostoevsky, Gogol, Chekhov, Mussorgsky or Kandinsky.

Since the 19th century, Russian pro-Western thinkers began to travel to Italy as a pilgrimage. In a famous episode of “Anna Karenina”, Tolstoy sneers at them when, having gone with Anna to Italy, Vronsky suddenly decides to become an artist. Lev Nikolaevich ironically describes a whole circle of Russian mediocre people, who imagine themselves smart alec simply because they “have joined the great European culture”.

And here a poem Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol wrote about Italy:

“Italy is a splendid country!

The soul groans and yearns for it.

It is all paradise full of joy,

Where glorious love meets spring”.

And a little further:

“The land of love and the sea of enchantments!

A resplendent garden in a worldly desert!

The garden where among the realm of dreams

Raphael and Torquat are still living!

Will I see you, while being full of expectations?

The soul is in the rays and thoughts speak for themselves.

I am attracted and burned by your breath, –

I am in heaven, I am all sound and flutter!..”

The poem was criticised, and poor Nikolai Vasilyevich, realising that he was not a poet, bought the entire circulation and wrote “Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka”, instantly becoming the most brilliant Russian prose writer of his time.

The writer’s attitude to Italy is interesting in this poem. It is not just love, it is awe. Here is what Sergei Aksakov wrote about Gogol: “He is a true martyr of high thoughts, a martyr of our time”.

“In my very nature there was the ability to imagine the world vividly only when I have retired from it. That is why I can write about Russia only in Rome. Only there it is in front of me as a whole, in all its bulk,” Gogol wrote.

Nina Berberova described in her memoirs “The Italics are Mine” in a very funny way how Gorky received her and Khodasevich like a lord in his Capri residence and how he cried in his office, reading Bunin’s stories published in the émigré press. Alexey Maksimovich was also very fond of Italy, and he lived there happily ever after, being very wealthy. But then for some reason he returned to the USSR. Apparently nostalgia tortured him.

Andrei Tarkovsky is buried in a Russian cemetery near Paris, but he did not like France. He loved Florence, especially Tuscan fabulous landscapes. He even bought a plot there and dreamed of building a house.

Another special “Russian” cult place in Italy is the Venetian island cemetery of San Michele. Three geniuses representing different generations of the Russian émigré are buried there. The famous Russian theater and art person Sergei Diaghilev, who died in 1929. Many believe that his Russian Seasons in Paris became the matrix of 20th century contemporary art. Not far from him, Igor Stravinsky, who died in 1971 in New York, is buried. He idolised Diaghilev so much that he wished to lie next to him. And that was done. Joseph Brodsky, who also died in New York but in 1996, is also buried there. Initially, the poet and the Nobel laureate had to be buried in the Russian part of the cemetery, between the graves of Diaghilev and Stravinsky. However, it was impossible, because Brodsky was not Orthodox. The Catholic clergy also refused to bury him. As a result, he was buried in the Protestant unit, under a modest wooden cross with the inscription “Joseph Brodsky”. Now there is a monument with an inscription in Latin: “Not everything ends with death”.

With all their external dissimilarities, Russia and Italy are very similar in fact.