The Russian diaspora has become Russia in miniature, carefully preserving the best of the lost homeland – its culture and spiritual values

By Ekaterina Grigorieva

As a result of social upheaval of the beginning of the 20th century – the revolution of 1917 and the Civil War, representatives of the political and cultural elite of Russia found themselves in forced emigration. Of all the countries of Western Europe, the largest flow of Russian migrants fell on France, and very soon Paris became the capital of the Russian diaspora.

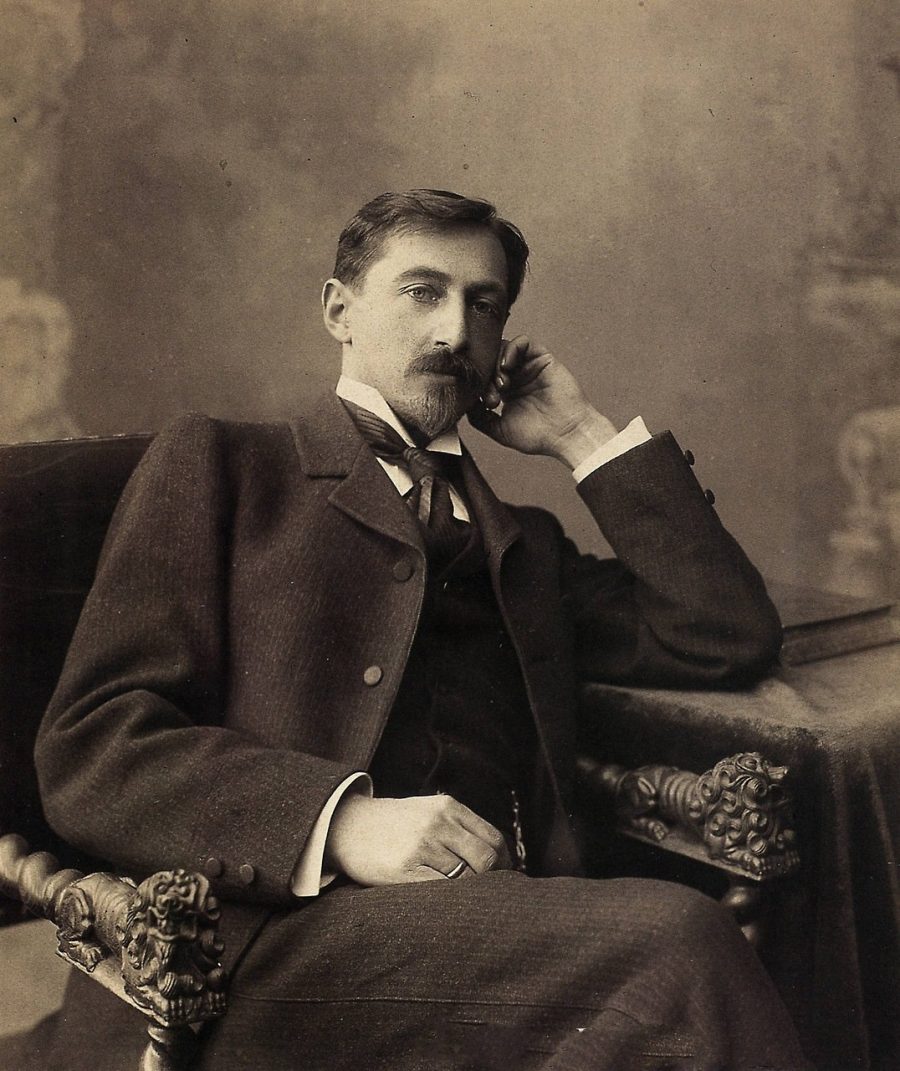

Pre-revolutionary Russia appeared in Paris in its full splendor. Grand Dukes of the Romanov dynasty, former ministers, senators, State Duma deputies, members of the Provisional Government and prominent diplomats settled there. By the will of fate, there were the largest Russian writers: I. A. Bunin, A. I. Kuprin, Z. N. Gippius, D. S. Merezhkovsky, M. I. Tsvetaeva, A. M. Remizov, I. S. Shmelyov, B. K. Zaytsev, V. F. Khodasevich, G. V. Ivanov and others. They brilliantly refuted the thesis of Soviet literary criticism, according to which a writer, when excluded from their homeland, is doomed to creative aridity.

Artists K. Korovin, A. Benois, I. Bilibin, Leon Bakst created their masterpieces in the city of arts. Russian ballet of Sergei Diaghilev shone on the Parisian stages, unsurpassed dancers, such as Vaslav Nizhinsky, Fokine, and ballerinas Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina and Matilda Kshesinskaya conquered the heart of the audience.

It was in Paris that the most famous emigrant newspapers (Last News, 1920–1940; Revival, 1925–1940) and magazines (Modern Notes, 1920–1940; Russia Illustrated, 1924–1939; Numbers, 1930–1934) were published. From 1920 to 1940, the Union of Russian Writers and Journalists operated in France, being called upon to protect the interests of immigrant writers.

In 1920, Maria Maklakova, a sister of the Russian ambassador to France, opened the Russian gymnasium in Paris. In 1923, composer Nikolai Tcherepnin, together with a group of professors from the St. Petersburg and Moscow conservatories, founded the Russian Conservatory in the capital of France, which continued the traditions of the St. Petersburg and Moscow conservatories and became the centre of music for Russian émigrés. Its honorary chairman was Sergei Rachmaninoff, and the first teachers were Feodor Chaliapin, Alexander Glazunov, Alexander Grechaninov… Starting in 1990, the Mayor’s Office of Paris began to regularly subsidise the conservatory.

The Russian diaspora has become Russia in miniature, carefully preserving the best of the lost homeland – its culture and spiritual values.

But life in a foreign land was not cloudless: the emigrants were deeply worried about the loss of their homeland, cherishing the idea of their soonest return; many worked hard just to survive. Officers of the White Army became taxi drivers, worked at the Paris automobile factories of Citroën and Renault.

Alexander Vertinsky, an outstanding Russian artist, a cult figure of the first half of the 20th century, singer and actor, wrote about Russian emigrants in Paris: “There were probably two hundred or three hundred thousand Russians in France. And there were eighty thousand of us in Paris. But we somehow were not very much in evidence. In this colossal city, we dissolved like a drop in the ocean. After a year or so, we already considered ourselves real Parisians. We spoke French, knew everything that was going on around us… But we also had our own way of life: our churches, clubs, libraries, theatres. There were our restaurants, shops, businesses, dealings. But these were for communication, for mutual support, to avoid getting lost in this country… The whole of Montmartre was teeming with Russians. All this audience was grouped around restaurants and night dances. Some served as garcons, others as head waiters, others washed dishes in the kitchen…”

Vertinsky admitted: “My France includes only Paris, but such Paris is the whole of France! I loved France sincerely, like anyone who has lived in it for a long time. It was impossible not to love Paris, just as it was impossible to forget it or prefer another city to it. Nowhere abroad have Russians felt so at ease and free. It was a city where the freedom of the human person is respected… Yes, Paris… this is a birthplace of my spirit!”

Ivan Bunin had lived in France for more than 30 years. He found himself in a foreign land at the age of 50 and had to start a new life. But he failed to find his second home in exile – Russia always remained in his thoughts. “We took Russia, our Russian nature, with us, and wherever we are, we cannot but feel it,” the writer said about himself and about many other forced emigrants who lost their fatherland.

On November 9, 1933, Bunin received joyful news from Stockholm that he had won the Nobel Prize in Literature “for the strict artistry with which he has carried on the classical Russian traditions in prose.” For the first time during the existence of this prize, a Russian writer was awarded in literature.

On November 10, Parisian newspapers came out with big headlines: “Bunin is a Nobel laureate.” For the entire Russian diaspora in France, it was a real celebration. The writer was showered by hundreds of telegrams of greetings, he was invited to the receptions organised by the publishing houses, various creative associations and unions. Magazines and newspapers sought to interview him.

In his banquet speech on the occasion of the Nobel Prize, Bunin said: “For the first time since the founding of the Nobel Prize you have awarded it to an exile. Who am I in truth? An exile enjoying the hospitality of France, to whom I likewise owe an eternal debt of gratitude.”

Such gratitude lives to this day in the souls of the descendants of the first waves of emigration from Russia. France is their homeland, but they continue to sacredly honour Russian cultural traditions and keep the memory of their ancestors.