Walter Schubart: ‘It is the tragic fate of prophets to see the misfortune approaching without being able to prevent it, and it is the equally tragic destiny of the actors in the drama that they are unable to see the misfortunes they themselves are causing’

By Kirill Privalov, editor-in-chief

No country in the centuries-old history of mankind has ever been subject to such a number of restrictive measures as modern Russia has. However, who wins and who loses from over 10,000 (!) Sanctions imposed against the Russians? The question is extremely relevant against the background of historical reminiscences, not least eighty-five years after Walter Schubart wrote the amazing book, Europe and the Eastern Soul.

‘I saw this book for the first time in the late 1930s and immediately got excited: I set about translating it,’ VDP (this is how in the Russian diaspora they called Vladimir Dmitrievich Poremsky, a profound thinker and a man with a difficult destiny, who for many years headed the National Workers Union of Russian Solidarists, the most active organization of Russian emigres and their descendants) told me in Paris in the late 1980s.

‘I was afraid to sign Schubart’s translation with my last name and chose a pseudonym: V. Vasilyev,’ Poremsky went on. ‘The first two editions were printed by polycopy, not a single printing house in Europe occupied by the Nazis would have accepted Europe and the Eastern Soul for publication. Why? Because the author, a philosopher and a historian, a German from Riga married to a Russian noblewoman, depicted such bold historical perspectives of Europe and Russia which did not suit the West. I must admit, it had bad consequences for both of us. Walter Schubart died in Kazakhstan’s Gulag, and the Nazis sent me to Sachsenhausen.’

Yellow, faded paper, 125 pages of small print. Prophetic incunabula. In the preface to the first Russian edition Poremsky who introduced himself as V. Vostokov, wrote in 1943: ‘Though this book was written by the author with the object of “European self-knowledge by the method of contrast,” it is primarily interesting for us Russians – in it many will be able to draw spiritual strength (which is more important now than ever before). It allows us to find the firm position that it is hard to find in the storm of military events and the conflicting feelings, doubts and concerns we are experiencing. This firm position can only be found by moving away from the vanity of our days to the heights from which not problematic tasks for tomorrow, but broad historical perspectives open.’

So, what was explosive in this book? What does the ‘Eastern soul’ have to do with it?

‘The problem of the East and West is primarily a spiritual problem,’ Walter Schubart says. ‘Russia did not crave to enrich herself by conquest… The Russian soul finds its greatest happiness in sacrifice.’ Meanwhile, Europe did not ‘claim to have a mission to fulfil towards Russia. At the most, she desired concessions or economic booty.’

‘We are living in a period of transition, and this is the cause of unrest and conflict,’ Schubart defines the historical framework of research. ‘Our age, although a melancholy one, is nevertheless full of hope. A sense of doom but at the same time a feeling of promise characterise this epoch of ours. We are living through several decades of great upheaval between an age that is dying and one that is coming to birth. For it is neither a race of men nor a culture that is dying before our eyes; it is an era.’

And further: ‘Once more, Europe was possessed of two ideas only: Russia and the counter-revolution (of the Fascists). With the year 1914 we entered upon the century of wars between the East and the West. Since then, it has become increasingly evident that in the future all great crises will have their origin in the East and will occur in the East… It is the problem of the historical struggle for supremacy between that continent known as Europe, and Russia – between the Western and the Eurasian continents. For like India or China, Russia is a continent which today contains human beings of 169 different nationalities, with representatives of all the world religions… The Eastern frontiers of Europe are on the Weichsel, and not in the Ural Mountains; as in the Middle Ages, they come to an end there where the Germanic settlements made halt.

‘That Russia has begun to feel herself to be a continent is shown clearly by her policy concerning nationalities; this policy does not discriminate among individual races, peoples or tribes… Thus, we see that two political tendencies have determined the course of modern history. The purpose of the one was to separate the West more and more from the East, that of the other to bring about… the downfall of a Europe which can no longer so easily survive the loss of blood occasioned by murderous wars and revolutions as the inexhaustibly fertile East. Whether we consider the development of culture or of politics, the same picture presents itself to our view: we see that the centre of gravity has moved in an easterly direction…

‘The Messianic attitude of the Russians goes back as far as the sixteenth century. It made its first appearance in the writings of the religious author Filofei, who was the Staretz [a spiritual elder]of the Jeleasar Monastery [The Eleazar Monastery of the Saviour] in Pskov. He originated the doctrine that Moscow was the Third Rome whose mission it was to unite in itself the first and second (Byzantine) Rome. Here we are already face to face with the chief characteristic of the true Messianism, which at once proves that it is devoid of all imperialistic aims. Messianic man unites the divided, while the imperialist separates the united. Filofei did not suggest in his teaching that Moscow should either supersede, succeed or surpass Rome or Byzantium. He only proposed that it should absorb them in reconciliation with one another. Russian Messianism has always been accompanied by the desire for reconciliation.’

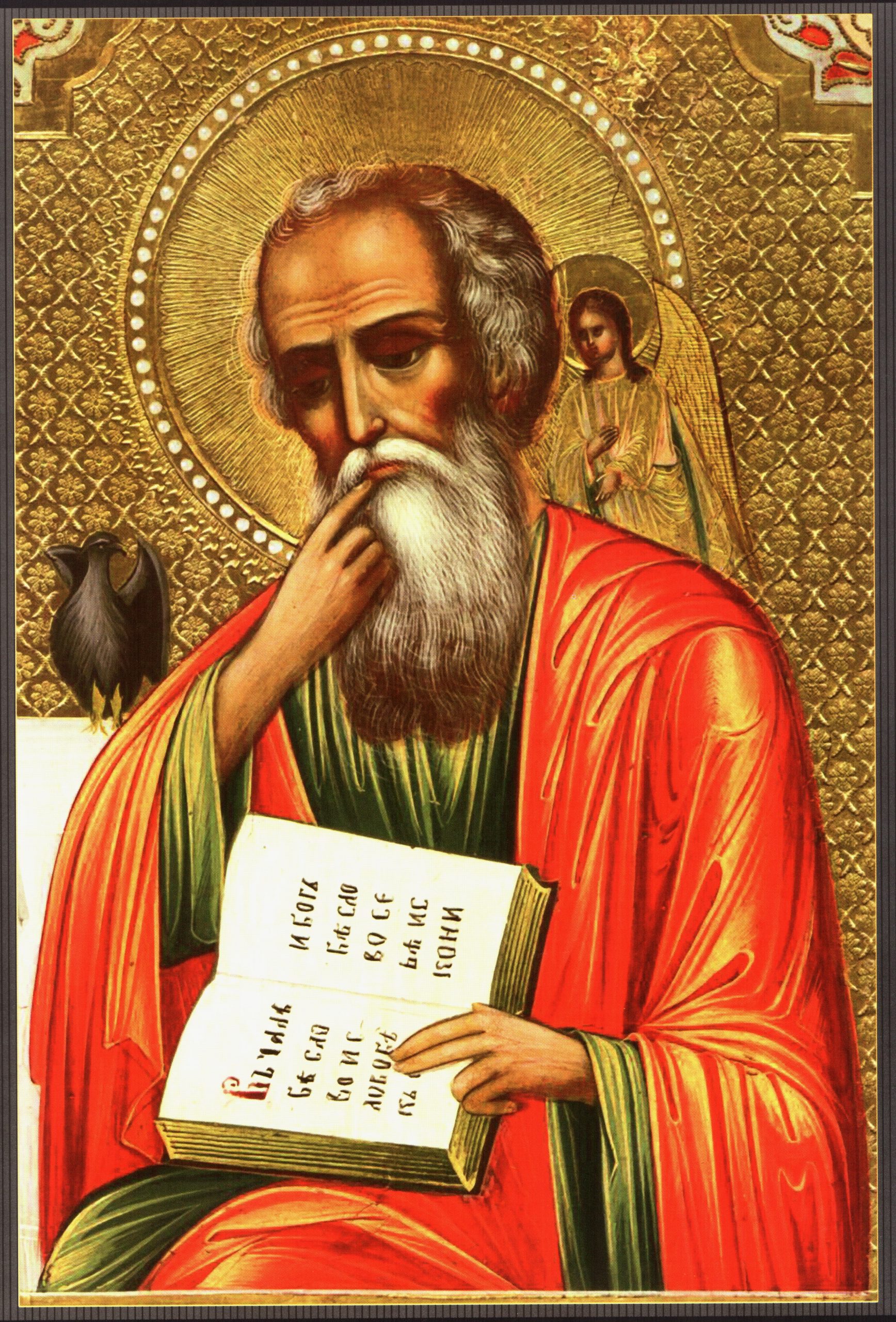

Walter Schubart contrasts two cultural archetypes, two different types of man – St John the Evangelist and Prometheus (these are Russia and the West respectively): The man of the John type makes a sharp distinction between good and evil; he vigilantly notices the imperfection of all actions, customs and institutions, never being satisfied with them and never ceasing to seek perfect goodness. He considers earthly values as relative and does not elevate them to the rank of “sacred” principles, and therefore he is able to quickly go from seemingly boundless humility to the most unbridled and infinite rebellion.

Promethean man is quite different. For him ‘the world is chaos into which it is his mission to bring order and form.’ Promethean man is full of thirst for power, he moves ever further away from the spirit and goes ever deeper into the realm of things. He strives to build those who are not like him in his own image and likeness… So, there is a confrontation of absolutely different virtues: tolerance and activity, harmony and sensation, thoughtfulness and work…

‘Promethean culture is based on number. Galileo demanded that everything measurable should be measured and that the attempt should be made to render the rest measurable. To count is to divide. Statistics is a truly European science, which is… foreign to the Russian. They do not count – they estimate the value of things. Promethean man is the man of parts; he is a specialist. He is a virtuoso within a narrow intellectual domain. In neighbouring territory he is an illiterate. With all his excellencies and deficiencies, the Russian is possessed of universal vision. He views the Whole, but in doing so overlooks much detail.’ The Russians cannot divide and cannot be satisfied with a part. They want everything at once, and if it is impossible, they do nothing and have nothing…

Primal fear is the secret engine of Promethean activity, and primal trust is the prerequisite for Russian contemplation. The danger for Europeans is that they cannot wait, while the danger for Russians is that they wait too much. Primal fear makes you too hasty, and primal trust makes you too slow. Patience is lacking there, and determination is lacking here. The Russians and the Europeans have a completely different sense of time.

…‘The Russian does not live his life from the standpoint of “I” or “You” but from that of “We.” Personal contrasts are not of first importance to him: of primary importance to him is his relationship to an indivisible Whole which he rediscovers in all human beings…’

The feeling of brotherhood makes life much easier and more bearable for the Russian than for the European with his instincts for struggle, plunder and competition… ‘How typical of this brotherly attitude is the custom in Russia of dispensing with title and honours, and calling people by their patronyms! It is the sign of a genuine democracy of the spirit…

‘I already hear an objection. Has not brotherliness existed in Europe as well? Was it not one of the ideals of the French Revolution? Yes, it was! But it is the same with brotherliness or fraternity as it is with freedom, atheism, socialism or liberalism – these words have not the same meaning in both East and West. The fraternity of 1789 was not the expression of an organic feeling of brotherhood, but a formula for the equalizing of the external circumstances of political and social life. It was equality once more. And freedom was not the attempt to reach out beyond the confines of personality, but the desire to open up personal competition to all on equal terms. This was equality for the third time. All external barriers between human beings were to be levelled.’ Such was the general meaning of freedom, equality and brotherhood.

‘Since the time of Peter the Great, Russia – not entirely without fault on her side – has been involved in the process of European self-destruction. Russia seized avidly upon modern European ideas, and with the typical extravagance and excess of her national character carried these to their extreme consequences in the Soviet state where their inner impracticability was revealed and magnified a hundred times for all the world to see. In doing this, Russia succeeded in refuting these ideas, and now the second act of the drama begins. The way has been cleared for the awakening forces of the East.

‘Promethean man has begun to be aware of his coming downfall. He is trying to escape from reflection and from solitude. He is endeavouring to escape through narcotics into pleasure, work, or into the crowd. Only not to be free – only not to feel any responsibility! Rather obedience and slavery! He is not only a slave, but he desires to be one! He is grateful to Caesar for depriving him, with his freedom, of the torture of self-determination. He embraces the whip that flays him. That is the essential nature of contemporary collectivism…

‘Thus – as so often before – it is once more the tragic fate of prophets to see the misfortune approaching without being able to prevent it, and it is the equally tragic destiny of the actors in the drama that they are unable to see the misfortunes they themselves are causing. Impotent seers – unsuspecting rulers! But there is a deeper meaning in all this. If the warning voices were not to fall on deaf ears, the ultimate collapse would not be so certain.

‘Russia – not the present but the future – is the refreshing wine capable of renewing the exhausted life of modern humanity; Europe is the durable vessel in which to preserve the wine. Without the solid form to keep it together the wine would be spilled over the country; without the wine that fills it the precious cup remains an empty and cold showpiece alienated from its purpose. Only when wine and cup meet can mankind most fully enjoy them.

‘Modern Europe is form without life; Russia is life without form…’

In the renewal of humanity, connected, or rather, coinciding with the task of Western-Eastern reconciliation, the emphasis should be laid on the Russian side, on the side of life, not form. ‘Not the European, but the Russian, possesses the fundamental attitude through which man will eventually discover the true purpose of his existence. The Russian mind is directed towards the Absolute – he has “universal” feeling and a Messianic soul. Hence, we repeat that in all essential questions of life, the European must accept the Russian as a model – and not the other way round. If he desires to find his way back to eternal values, the European must acknowledge the world outlook of the Russian. It was this that Dostoyevsky meant when he demanded that every single one of earth’s inhabitants should first of all be a Russian!

‘Let us remind ourselves once more that the Englishman desires the world as a factory, the Frenchman as a salon, the German as an army barracks, the Russian as a church. The Englishman seeks gain, the Frenchman fame, the German power, and the Russian sacrifice. The Englishman desires to exploit his neighbour, the Frenchman to impress him, the German to command him – only the Russian desires nothing from him. The Russian has no desire to use his fellow men as the means to an end. And this is the core of the idea of brotherhood… This is also the Gospel of the future.’

It seems to me that hardly anything essential can be added to this, which was written eight and a half decades ago.