The Fire of Moscow began during the occupation of the city by French troops on September 2, 1812 and lasted four days

By Leonard Gorlin

As the French army advanced towards Moscow, the towns and villages lying between the western border of Russia and Moscow were filled with rumors of French brutality towards the local population. Although there were indeed many cases of violence, such stories were either seasoned with terrible details or simply invented. But urban and rural populations frightened by them left their homes and moved far inland.

After the Russian army left Smolensk, a mass exodus from Moscow began. Most of the inhabitants left the city in the first half of August 1812; of the 270,000 Muscovites, a little over 6,000 remained in the city. But besides them, about 9,000 wounded and sick Russian soldiers and officers, who could not be supported to Yaroslavl or Rostov the Great, remained in Moscow.

Local fires began in Moscow, when French troops were still on the outskirts of the city. But by the time Napoleon entered the Kremlin to the Marseillaise sounds, the fire had engulfed almost the entire Zemlyanoy Gorod and Bely Gorod, as well as significant territories on the outskirts, destroying three-quarters of the wooden buildings.

According to the official version of the tsarist government, the fire was caused by the invaders’ actions. There were some grounds for this version: the French soldiers set fire to the New Artillery Yard, the Pravoberezhny Arsenal and the barracks on Tverskaya street, and the fire could spread to neighboring streets. But it is also known that the police and the Cossacks led by the Moscow mayor Rostopchin, taking advantage of the fires that had begun, decided to turn the city into a fiery hell for the invaders. For example, Rostopchin issued the order to set fire to some public stores, judicial offices and river boats, as well as the Moskvoretsky Bridge and the barracks in the Kremlin.

Count Fyodor Vasilyevich Rostopchin was a prominent Russian statesman, a general of infantry. During the time of Emperor Paul, Rostopchin was his favourite and de facto managed his foreign policy. He was also a publicist and a patriotic writer. Being the Mayor and the Governor-General of Moscow under Alexander I, Rostopchin clearly understood that if French troops settled in the Kremlin, it would not be easy to expel them from there. In addition, for Rostopchin, who was a patriot and an Orthodox person, the very idea of the French army occupying the Kremlin, destroying, robbing and defiling Russian churches, was unbearable. Actually, this is what happened: in the Cathedral of the Dormition, next to the tomb of the Russian tsars, the French set up a stable. On top of that, there were rumors that Bonaparte considered the Kremlin architecture as medieval and barbaric and intended to rebuild it completely. Rostopchin decided to literally smoke Napoleon out of the Kremlin.

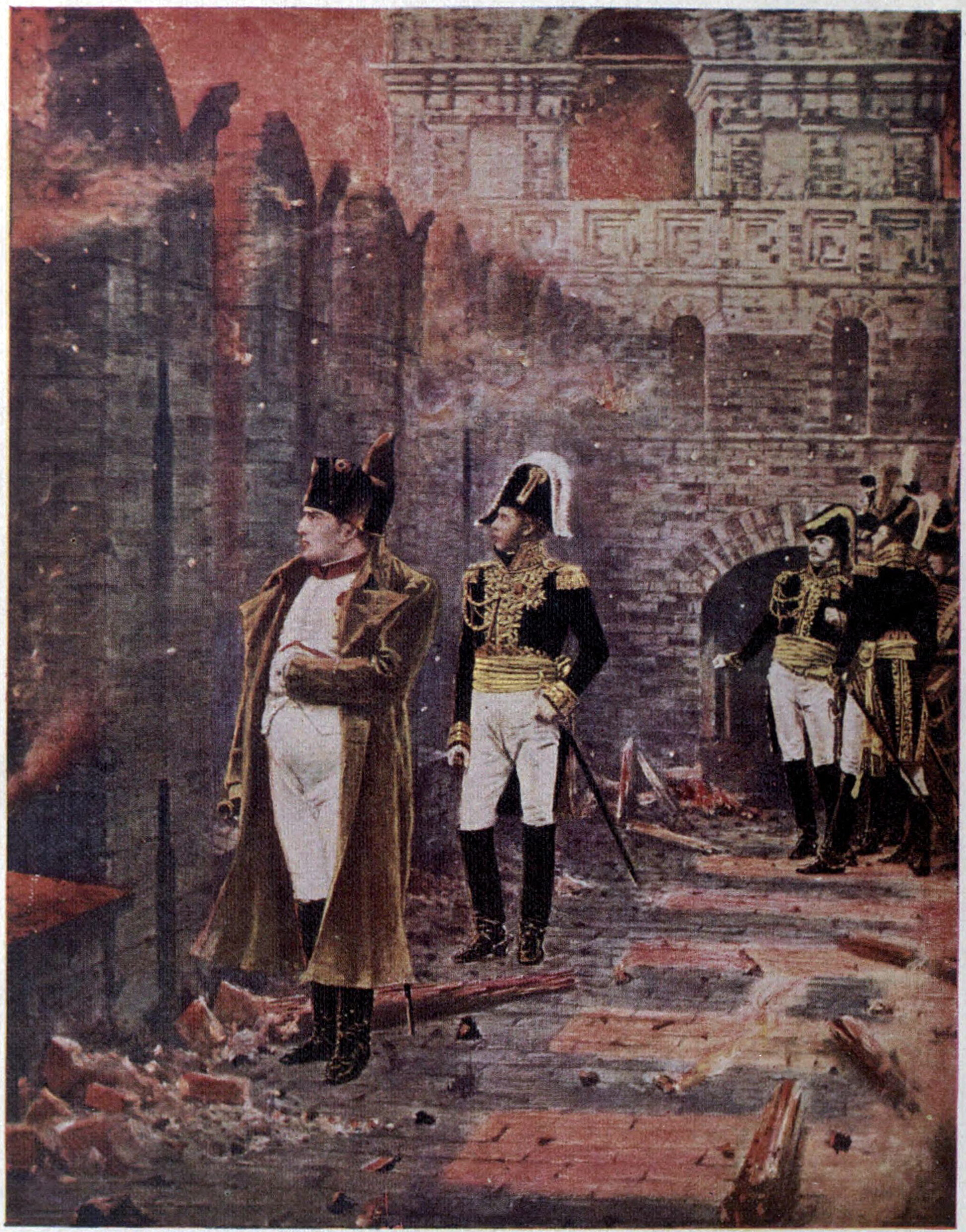

By the night of September 3, Moscow had become a huge bonfire: the fire quickly spread from Pokrovka and the German Quarter to neighbouring quarters. Houses, storehouses, food and building materials warehouses were burning. Napoleon looked at the burning Kitay-Gorod from a viewing point on the Borovitsky Hill and silently cursed: his grand entry into the Kremlin turned into a terrible disaster, which, as he suggested, would attach a “new Nero” epithet to him. And so, it really happened.

The next day smoke and fumes made it impossible for Napoleon and his entourage to stay in the Kremlin. The French emperor left the burning Moscow together with his retinue and headed for the Arbat, but houses were already burning in its back alleys too. Trying to get around the burning quarter, the French got lost and somehow made their way to the village of Khoroshevo. From here they went to the Moskva River, took the ferry to cross it and, passing by the Vagankovo Cemetery, reached the Petrovsky Palace in the evening. It follows from the notes made by the emperor’s adjutant, that the fire pursued them for a long time, destroying one street after another.

Napoleon spent three days in the Petrovsky Palace and returned to Moscow on the fourth day: there was no longer a city in front of him, he saw only ruins and ashes.

The fire subsided by the morning of September 6, making a bonfire of three-quarters of the city. Returning to the Kremlin, Napoleon ordered that the arsonists be found immediately. The French made no bones about those they met on the streets. They seized townspeople and policemen in the city, who, like the peasants from the suburbs, were accused of arson, and some were declared fugitives. All those caught were recognised as arsonists, and on September 12, executions began in the Kremlin and on the city squares. The French executed 400 Moscow inhabitants without any trial.

The death of 9,000 wounded and sick soldiers and officers who still remained in the city became a terrible tragedy for Russia and its army: they were burned alive. General Aleksey Yermolov recalled the thousands of burnt soldiers: “It was heartbreaking to hear the groans of the wounded, who were left at the mercy of the enemy.” The French command believed that those who were recovering could organise partisan detachments, and therefore committed brutal reprisals against the wounded Russians. The French guards attacked the Kudrinsky hospital, which was located in the Widow’s House, where thousands of wounded Russian soldiers were cared for, and killed them all. The French fired cannons at the hospital, threw combustibles through its windows…

The occupation of Moscow by the French lasted 34 days. On October 6, Napoleon ordered his troops to leave the city that they had almost completely plundered. During the retreat, the Great Army mined the Faceted Palace, the Arsenal, the Ivan the Great Bell Tower, as well as the walls and towers of the Kremlin. Explosions began on the night of October 8 to 9, after the last French detachment left the ancient capital. Fortunately, they failed to blow up the Ivan the Great Bell Tower and the Faceted Chamber.

Already on October 10, the Russian cavalry avant-garde under the command of General Alexander von Benkendorf entered the city. This saved the few surviving buildings from new fires. To the surprise of the cavalrymen, peasants from all over the district flocked to the city with carts: they hoped to profit at least something in abandoned houses and, of course, in the Kremlin. A huge crowd tried to penetrate there, but the Guards Cossack regiment forced the crowd to withdraw and prevented the invasion of the Kremlin through gaps in the walls formed after breakdown. The crowd immediately switched its efforts to the French falling behind their army.

Two-thirds of important city buildings burned down in the fire, including the building of Moscow University, the rich library of Dmitry Buturlin, the Arbat Theater. The Moscow Orphanage, located next to one of the fire locations, was extinguished by soldiers led by General Ivan Tutolmin. However, several historical buildings have been preserved in the city, and among them, the oldest civil building outside the Kremlin – the Old English Court of the 15th century, as well as the oldest “multi-storey building” of the city – a drying room of the Simonov Monastery. The town house of the mayor also remained intact. According to experts, the fire destroyed about 6,500 residential buildings out of 9,000, including more than 2,500 stone ones, about 8,500 warehouses, shops and barns, about a third of the temples. Two-thirds of the churches were sacked by the French.

Many valuable documents and cultural artefacts of Russia perished in the fire. The list of them included such treasures as the copy of the Tale of Igor’s Campaign from the collection of Count Musin-Pushkin and the Trinity Chronicle. The total damage caused to the city and its inhabitants was estimated by historians at 320 million roubles (about 600 billion roubles in today’s money).

The city had been reviving for more than twenty years. In February 1813, following the proposal of Fyodor Rostopchin, Emperor Alexander I established a Construction Commission in Moscow, which was abolished only thirty years later. Rostopchin became the head of the Commission, Osip Bove became the chief architect, and Yegor Cheliev became the chief engineer. Such major architects as Domenico Gilardi and Afanasy Grigoriev took part in the restoration of the city. Bove’s function was to ensure the harmonious image of the reconstructed Moscow, and, given his talent and experience, it was hardly possible to find a more suitable candidate for the chief architect post in post-fire Moscow. In 1813-1814 the reconstruction of the Red Square was carried out under his leadership, and the destroyed Kremlin towers and walls were restored. And a few years later, Alexander Garden was laid out near the Kremlin wall in memory of the victory over Napoleon. According to the plan, the Kremlin was to be surrounded by a ring of squares; Bolotnaya Square became one of the main ones. The city has significantly increased the number of garden squares.

The great achievement of the Commission, as well as the Moscow nobility and merchants, was that by 1816 the main part of housing stock in Moscow was almost completely restored, although due to a lack of financial resources and building materials, many wooden houses were still being built in the city. If we talk about the construction of stone buildings, the revival of the city was marked by the appearance of a variety of classicism known as “Moscow classicism”: the architecture of mansions and public buildings was distinguished by unique shape plasticity, modest but elegant decoration and refined proportionality.

Many streets were expanded, including the Garden Ring. The townspeople appreciated it when cars appeared in Moscow 100 years later.

Count Rostopchin played a special role in the life of both Moscow and Russia. He remained in the combat army after the fall of Moscow. The count manifested himself as a proactive organiser and propagandist: he composed leaflets, traveled around the villages calling on the peasants to partisan actions, and he managed to convince many to start fighting against the French. In his estate Voronovo, he emancipated his serfs and burned the house and the horse farm.

After the French left Moscow, Rostopchin helped food supply to get back on track to support the population returning to the city. To prevent epidemics, the count created special detachments and organised the removal and disposal of the human corpses and horse bodies in Moscow and on the Borodino Field.

Under the leadership of Rostopchin, work began on the restoration of the Kremlin, the walls and cathedrals of which the French tried to blow up. The Construction Commission headed by Rostopchin received five million roubles for that purpose. Previously, the treasury allocated two million roubles for the distribution among sufferers, but such amount was not enough, and Rostopchin became a scapegoat for many: accusations and reproaches from the disadvantaged people rained down on him. These accusations, as well as the widespread belief that he was responsible for the Fire of Moscow, outraged Rostopchin, who devoted so much time and energy to the revival of Moscow after the departure of the French.

And it should be noted that the most irreconcilable accusers of Rostopchin were, first of all, those who treated the French with sympathy or collaborated with them in one way or another. And Rostopchin, immediately in the first months after returning to Moscow, ordered to restore supervision over the Freemasons and Martinists and established a commission to investigate cases of cooperation with the French.

Rostopchin had many things to do: in particular, he was responsible for recruiting, as well as for collecting artillery abandoned by the French. After the victory, Moscow had to create a monument from the collected cannons “to humiliate and obscure the self-praise” of the aggressor.

By that time, Rostopchin began to face health problems, and Alexander I, returning from Europe, accepted Rostopchin’s resignation as governor in 1814.

The count spent some time in Saint Petersburg, but constantly felt the hostility of the imperial court. In May 1815 he left Russia to undergo a course of treatment in Carlsbad and hoped to return home soon, but it turned out that he spent eight more years abroad. He enjoyed a reputation as a celebrated war hero in Germany and elsewhere; the kings of Prussia and England considered him as a great patriot of Russia and received him with pleasure. The ingratitude shown by his compatriots, apparently, was the reason why Rostopchin settled in Paris in 1817, periodically traveling to Baden for treatment, as well as to Italy and England. Formally considered a member of the State Council, Rostopchin returned to Russia in 1823 and petitioned the emperor for his complete resignation. He suffered paralysis and died in Moscow in January 1826.