By Nina Paavolainen, This is Finland

Finnish literature is going further than ever.

Bertolt Brecht once noted that Finns are silent in two languages. Maybe so, but they write in three – Finnish, Swedish and Sámi – and the total number of titles published annually in Finland is tremendous. The country sees the publication of 13,000–14,000 books a year, over 4,500 of them new works. Only in Iceland are more books published per capita.

Finns are also diligent readers, and the country’s extensive network of free libraries is largely to be thanked for this. Free admission to the world of knowledge is the key equalizing principle in cultural policy, and the figures are convincing: an average of over 19 library loans per resident per year. The library institution is vital for authors as well, as the compensation they receive from loans is an essential source of income for many.

In Finland, reading is a hobby that begins in the home at a young age: according to a study by Statistics Finland, about 70% of parents read out loud to their children. The latest PISA studies award Finnish pupils good results in reading skills, and in addition to the Disney characters known worldwide, favourite literary figures for Finnish children include Tove Jansson’s Moomintroll, who has appeared in just about every corner of the globe, and Ricky Rapper, whose adventures have been made into incredibly popular family films. One more revealing statistic: every third Finn reads literature every month, and this figure has remained stable since 2000.

Although the battle for readers’ free time has escalated – reading, after all, is a time-intensive activity – sales of literature have not notably declined since the turn of the millennium, and according to a 2008 ‘Finland Reads’ study, 16% of Finns buy over ten books a year. The 2010 statistics reveal a distinct, over 10% drop in total sales of literature – the first ever. Nevertheless, the book has maintained its position as a prestigious gift, despite the fact that, as elsewhere, paperback markets have expanded and new works are sometimes available in paperback during their year of release.

On the other hand, reading groups, social media, and popular blogs on literature have extended the group that critically assesses and recommends books. Although reading is a private experience, there is a desire to share it. In this sense, literature is a broad adhesive surface that binds people together.

With its e-books and print-on-demand, the current publishing environment has transformed the traditional role of the general-interest publisher. In recent years, Finland has seen the establishment of professionally run small presses that focus primarily on Finnish literature and nonfiction, with some degree of translations. Along with this development and in accordance with international trends, Finland has also seen the founding of its first literary agencies, which sell Finnish authors’ translation rights abroad, an activity that has traditionally been the sphere of publishing houses.

Furthermore, there has been growth in the sale of these translation rights: currently, approximately 200 Finnish titles appear in translation each year in almost 40 languages. The greatest number of these titles are published in Germany, with Sweden and Estonia following, but there are also, for instance, significant numbers of translations into Japanese. Finland has a broader tip of good literature these days, translator training has been bolstered, and sales efforts have been intensified.

The new generation of writers, born in the 1970s and ‘80s and raised in an international environment, is gradually solidifying its position. Many of them write flexibly across genre boundaries: poems and prose, for children and adults. Literature by immigrant writers has also started to appear. The polyphonic voice of contemporary Finnish literature is carrying further than ever.

On Finnish prose

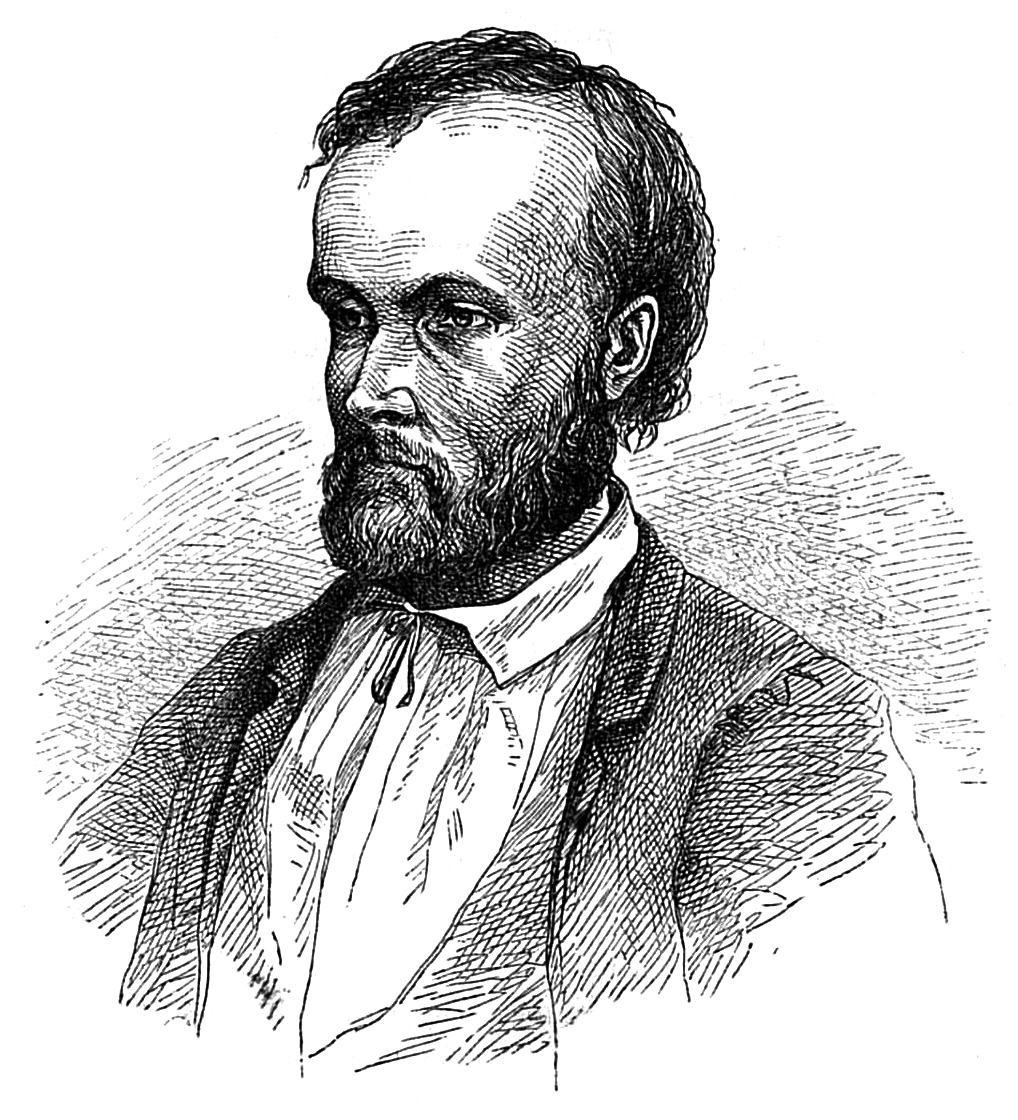

At the end of the first decade of the 21st century, Finnish literature bears international comparison well in terms of multidimensionality, despite the fact that Finland does not boast a particularly long literary history. National author Aleksis Kivi was the first master of Finnish-language prose, and his output coincided with the postromantic decades following the 1850s, while the Finnish national epic The Kalevala, compiled by Elias Lönnrot, appeared in 1835.

It should be noted that The Kalevala still holds influence today: even if you’ve never read it, its body of stories and imagery continue to have a powerful effect on the collective Finnish imagination. Comic book artist Mauri Kunnas’ The Canine Kalevala (new edition 2006) and a simplified version of The Kalevala intended for children (2002, English version 2009) remain incredibly popular. The Kalevala has been translated into over 60 languages, and Aleksis Kivi’s best-known work, Seven Brothers, which crystallises the tension between rural and urban, primitiveness and civilisation that has long shaped the core of Finnish identity, continues to be a favourite and benchmark for authors.

In Finland as elsewhere, the biggest sales figures are achieved by detective novels (Matti Yrjänä Joensuu, Leena Lehtolainen), thrillers (Ilkka Remes), family sagas (Laila Hietamies) and why not chick-lit-influenced portrayals of urban women (Katja Kallio). Also enjoying newfound status as a top-selling genre is the domestic comic book (embodied in such characters as Viivi and Wagner).

In addition, other quality prose is written in Finland, which in terms of style and subject more and more frequently finds its way across the nation’s borders.

The historical novel

Finnish literature has always included a powerful historical awareness. In the years of post-war growth and creation of national unity, literature had ideological tasks to fulfil, and up until the 1970s, it contributed to discussions surrounding the construction of the welfare state. Prior to this, Mika Waltari – in whose production novels situated in the past are read as depictions of the societal climate at the time of publication – created the 1945 work The Egyptian, which was translated into dozens of languages. Its status as a classic is by and large founded on its fundamental humanism, and Waltari remains among Finland’s best-known authors abroad.

Sofi Oksanen’s Purge (2008), one of Finland’s biggest international breakthroughs in recent years, revitalises the historical novel. Its Estonian-Finnish framework, fixed against a backdrop of recent European history, has spoken to readers as far away as the US, and in Finland alone the book has sold over 160,000 copies.

The popularity of Purge can be explained through a variety of factors. It takes a bold approach to the recent history of Finland’s sister nation, and its interpretations of the events of the Second World War, the relationship between the conqueror and the conquered, have generated much debate. The heroes end up turning into the losers, and during wartime everyone loses something, not least of all themselves.

Oksanen’s narration is not anchored in the tradition of realism; it is carried along by a profuse flow of lush and lingering verbs. The strong female perspective opens up a view to a mental landscape whose experiences have not received equal exposure. It gives a voice to a muzzled distress that no one has wanted to hear, and this is likely one reason why the work has tapped into such a broad base of identification. The story of three generations of women fleshes out the themes of nationalism and femaleness: women’s bodies and women’s work are both concretely and metaphorically instruments of warfare in which subjugation, humiliation, and shame are ever-present.

Furthermore, Sofi Oksanen represents the younger generation of writers in that she is happy to meet her readers, travels abroad continuously to speak about her work and raises topics of current interest when she makes an appearance. The media continues to write more about writers as phenomena rather than literature itself, but shifts in the publishing field and seemingly dramatic changes of publisher feed this orientation as well.

Examples also exist from recent years of the historical novel’s fragmentation to deal more problematically with the construction of Finnish identity over the last century. A fine illustration of its expansion into the mental-historical arena is Jari Järvelä’s trilogy, whose final segment has been appropriately named Kansallismaisema (‘The National Landscape,’ 2006). As old as his century, in other words 38 years old in 1938, the protagonist takes centre stage as the author carefully describes the painful birth of a common culture.

Jari Tervo, who has long belonged to the first tier of Finnish authors, frequently and very amusingly portrays ‘the common folk,’ particularly the people of northern Finland. His works that appeared in the years leading up to the 2010s, a trilogy that deals with Finnish history, do not form a chronologically linear whole: we begin from the Cold War era and end in 1920, in the period following the Finnish Civil War. Instead, it re-draws key turning points from the nation’s recent past, which in Tervo’s interpretation are linked by the fight against communism.

Leena Parkkinen’s strong debut Sinun jälkeesi, Max (‘After You, Max,’ 2009) resurrects the past milieu of 1920s Helsinki, but its broader framework is the European worldview and its questions universal. Siamese twins and circus performers Max and Isaac tour Europe, embodying the thematics of difference and otherness: How is it possible to live separately and yet forever side by side?