On 28 November, the Orthodox Church began the Nativity Fast

Augustin Sokolowski, Doctor of Theology, priest

Fasting in the Orthodox tradition is much more important than simply abstaining from certain foods and drinks. Fasting is the poetry of the harmony of body and soul, born of the refusal to give in to their demands. Fasting is a refusal to become unnecessary and superfluous. Fasting is the beginning of something new, fasting is also the beginning of Christmas.

Fasting is a time when – far away from the city, in the desert, in the snow or in warm latitudes – one seems to reach out to the stars, thus bringing God closer to us. God looks at us more lovingly, kindlier, more humanly. Lent is a time when God is especially still. He looks at us and pretends not to hear. God simply becomes quieter.

Of course, these biblical analogies are difficult for us children of postmodernism, the “descendants” of Jean-Paul-Sartre with his definition of man as self-affirming freedom without God. Let us not forget, however, that in the Bible God lives, loves, laments over our sins, mourns and rejoices. God has ears, hands and feet and he has eyes. In the Bible, God can even… sleep. Or, as it says in the Psalms, “But as from a dream the Lord arose, like a giant defeated by wine” (Psalm 77:65). God defeated by wine! Or, as the “Memorial” of the philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) says during the Christmas season of 1654, “Fire. God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, but not God of philosophers and scientists. Trust. Feeling. Joy. Peace. God of Jesus Christ”.

The ancient tradition of the Church calls the Nativity Fast “Advent”, which means the “time of coming”. The Lord draws nearer day by day, drawing nearer to the world and to the Church on Christmas Day. When we say this and recall what happened more than two thousand years ago at the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, we are by no means performing some kind of “mystery”, as if we were trying to reproduce that once and for all took place in history… No. But, at the same time, each time in a new way and directly, as if for the first time, we see what happened then. Let us be aware of it. In our heart, in our mind, in our feelings and in our body. “In our laughter and in our tears.” Lent is not a time of dieting, but a time of drawing near to the Lord Jesus. The work of God that He once did, having entered into history, settled in time, became temporary and historical, and became one of us. This work was done before God but continues to end in history. In this sense, the world and its redemption are the work of God. Moreover, there is no salvation outside the world. Therefore, God will never abandon this work of His.

Existing in time, we grow older every moment. “Ten minutes older”, as the title of the film of the same name says. But from the Bible we also know that we are transient except for time. And this temporality of ours is surrounded by illness, sorrow, sadness, suffering, as well as happiness, fun, smiles, laughter, and joy. These two so completely opposite qualities of our being in the Christmas season are ordered according to God’s plan.

In Christ Jesus, God once entered history and took on our everything. In return, he gave us all his own. In order to enter into the Christmas season, it is necessary to have recourse to the sacraments more often. A sacrament is a visible blessing given by the Lord on the journey of life. Sacrament is a part of God’s Work when He takes upon Himself our sicknesses, sufferings, mistakes, thoughtlessness, stupidity, strangeness, incomprehensibility, and tragedy. For our healing, God makes our tragedy a part of His cross. That is, it connects with what He Himself once did when He was born, entered history, and ascended to the Cross. It turns out that the Lord takes upon Himself what is inconsistent in us and in the world with His plan for us. To reward us with mercy, blessing, a smile, and the approach of His eyes. When the stars will be near. And the world and we will see Him –the glorious Messiah who will comfort, Christ the Saviour.

Advent is the approach to the threshold of mystery. Advent is the time of the Nativity Fast. Advent is the time of faith. Advent is the time of faith in Advent as the Second Coming of the Lord. Advent is the expectation of “coming with glory to judge the living and the dead of the Lord Jesus Christ”, as it says in the Creed.

The pre-Christmas season has two faces: sadness and joy. And if the meagre expression of this time begins exactly forty days before Christmas in the tradition of fasting, then the joyful, festive anticipation of Christmas receives its first revelation in the Solemnity of the Presentation of Mary, the Entry into the Temple of the Most Holy Theotokos, which the Church celebrates on 4 December. On this day, according to tradition, the Church celebrates the Presentation, or in modern language, the first visit of the infant Mary to the Temple of God in Jerusalem. A visit that became a dedication when she herself was consecrated to God.

Like the run-up to Christmas, the feast of the Presentation itself has two sides: joyful and sad. The joyful side of the holiday is the approach of Christmas. At the same time, the Feast is a journey through time. Moving through history. Diving into the special world of the old glorious church of the New Rome – Constantinople. At that time, when the political capital of the Christian world, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, the city of cities, had at its heart the temple of Hagia Sophia, an architectural wonder, the temple erected by the Emperor Justinian (482-565) who exclaimed, “I have defeated you, Solomon!”

Orthodox services line up around the Hagia Sophia. From there it spread as the standard for the entire empire and thus the universe. The kings of Constantinople saw themselves as successors to the Kings of Israel. At that time, rites were written, liturgical texts were introduced in honour of the righteous major and minor prophets of the Old Testament.

The liturgical texts of the Feast of Presentation are the incarnation of this Byzantine worldview. The perception of sacred things was due to this. The Byzantines or, as they called themselves, the “Romaioi”, (Romans), saw themselves as successors to the great biblical cause: the Temple, the Covenant, Sacred History. The glorious church, the most beautiful worship on earth, the temple in which God Himself dwells in the Sancta Sanctorum. The introduction of the young lady Mary into the sanctuary – what could be more right, and just, or better!

But if you suddenly forget the Byzantine Empire, another side of the same story is revealed. On earth, in the Old Testament – and in all human history – there was only one temple recognised by God. This was the temple in Jerusalem. One Temple in History. This Temple was inviolable and holy. The Holy of Holies was in it.

Mary, the Mother of God, is introduced into this temple. It is the great beginning for Her. But for the temple it meant the end – abolition, conclusion of its history. Since then, there will be no more temple on earth. Never in the history of mankind. The introduction to the temple of the Virgin as a farewell. The introduction to the temple as a farewell for the temple itself…

The New Testament is coming. And everything that seemed great and holy before is abolished. The temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD, never to be rebuilt. And the human being becomes the temple of God. That temple will be Mary entering the temple. Every person who is baptised and accepts the Eucharist becomes such a temple. “I will enter into them. I will walk in them. I will be their God” (Leviticus 26:12; 2 Cor. 6:16). This is what God himself predicted. God foretold that man would become a temple.

Every church is a meeting place. The Eucharist is celebrated in the church. In the church a person becomes the temple of God. The biblical Temple, the temple building, is no longer there. And this reality comes on the day of the holiday, that of the people who first became the temple, its dwelling place, and the Holy of Holies – their introduction into the temple is celebrated by the community today. The introduction as an icon of the world “here and now”. The Lord is always preparing new things for us (cf. Rev 21.5). This new coming is described in the Book of Revelation. And the celebrated introduction becomes an image yet to come. Soon the Lord will return. A new heavenly Jerusalem will descend from heaven. “And I saw a new heaven and a new earth. The former heaven and the former earth have disappeared” (Revelation 21: 1).

And the most important thing: in this New City, the heavenly Jerusalem that descends from heaven for the earth, the temple is no longer. “I have seen no temple in the city. Its temple is the Lord God Almighty Himself and the Lamb. For its consecration the city needs neither sun nor moon. It is flooded with the light of God’s glory; its lamp is the Lamb” (Rev. 22-23).

Our temple, the temple of peace and the temple of the universe, the temple of the Church will become … the Lord God himself. In the beginning the temple was a building. And this temple is now abolished. Today the young lady Mary becomes the temple, so that because of this gift we become the temple. Christ will soon return so that He Himself and our Father God can become the temple. “Both the Spirit and the bride say, Come!” (Rev. 22.17).

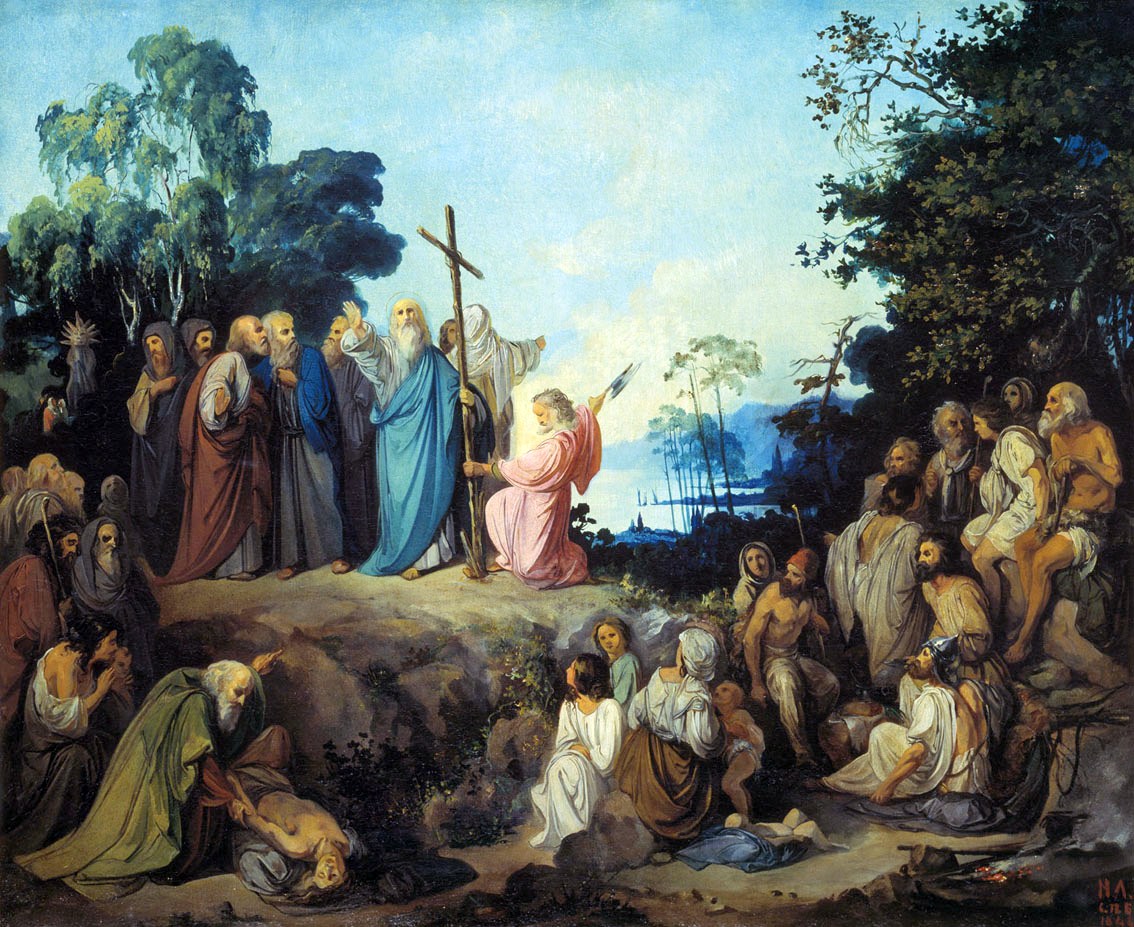

In the Creed, the community that proclaims its faith in the Church calls her “apostolic”. This means that the memory of the apostles is of great importance to the community. Therefore, on the commemoration day of St. Andrew the Apostle on 13 December –perhaps theologically most important commemoration of the saints of the entire Christmas season – we are called to reflect on the apostolicity of the Church.

The Apostle Andrew is called the “first-called” because, according to the Gospel, he was first called by the Lord to follow him (John 1:40-41). In John’s Gospel, it was Andrew who told the Lord, “There are five fish and two fry, but what is this multitude?” (John 6.9). In Matthew’s Gospel (Matthew 24.3) and Mark’s (Mark 13.3), when the Lord was sitting on the Mount of Olives opposite the Temple, “Peter, James, John and Andrew asked him alone when it would be and what sign when? all this must be done” (13.4). As the Lord prepared to celebrate his Passover on the cross in Jerusalem, Andrew and Philip proclaimed that the Greeks, i.e., the Gentiles, wanted to see the Messiah (Jn 12.21-22).

Tradition is also rich in testimonies about Andrew. Very early sources, for example, say that Andrew preached in the territory of modern Greece, among other places. Here, for calling to faith in Christ the wife of the procurator of Achaia, in the north of the Peloponnese, he was crucified on a cross made of two beams in the shape of the letter “X”. This cross is called “St. Andrew’s Cross”. According to the testimony of tradition, the crucified Andrew remained alive for two days and preached from the cross. Those who crucified him wanted to remove the apostle, but he gave up his spirit in the rays of the Divine Light, like the Saviour in the Divine darkness of the darkened sun.

Subsequently, in the countries where Andrew preached, new states arose, new peoples came. Each of them, including Russia, considers Andrew as their patron and apostle. By calling the Church apostolic, we are called to reflect on the meaning of this word.

– The apostolicity of the Church means that it was not only founded by the Apostles but has also preserved the continuity of pastoral and priestly ministry passed on directly and continuously from the apostles through the laying on of hands and prayer.

– The apostolicity of the Church is the original Christian and patristic conviction that those local churches which were founded directly by the apostles and mainly by Peter cannot err and sin in the truth.

– The apostolicity of the Church means that everything the Church teaches and holds concerning faith and morality was determined by the Apostles. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing can be subtracted from it. “If anyone adds anything, God will inflict plagues on him; if anyone takes away from the words of this prophecy, God will take away his participation in the book of life”, says the Scripture (cf. Rev. 22: 18-19).

– The apostolicity of the Church, and this is very important, is also its poverty. “The multitude of the faithful had one heart and one soul; and none of their possessions called their own, but they had all things in common” (Acts 4:32).

– The apostolicity of the Church means its readiness for mission. Readiness here and now, at all times of the day and night, in every corner of the world, to proclaim the risen Lord Jesus Christ.

Many of us were born and lived at a time when the New Year was celebrated as if time could give life. They waited for the coming of the new year, a new, renewed time, just as probably the first Christians awaited the return of the Lord Jesus every Sunday, the Lord’s Day.

According to the conviction of the first believers in Christ, the Lord Jesus was inevitably to return. Return unexpectedly to catch the unsuspecting world that is not waiting for Him. Return to shut down and thus complete history and time.

Now that we have come to God and Jesus Christ and gained faith, we know that time does not give life. It erases people, acquaintances and strangers, our relatives, and friends from the pages of life. It erases as a broom, sweeps away cities and peoples, countries, and civilisations. It takes away what is most precious and dearest, and erases parts of ourselves.

There is a certain irrevocability in the celebration of the New Year. On the days before Christmas, as we prepare for the coming of the New Year, we will remember in prayer those who are not with us. Let us remember those who have left us and remain forever in the last decade and the first year of the past, already new, third decade of the century.

Remembering those, who are remembered by few or no one, gives us hope that one day we too will be remembered. Our little prayer becomes part of the prayer of the Church which – we almost always forget this biblical truth – is the prayer of the Lord Jesus.

The prayer of the Lord Jesus is the prayer of the One who gave Himself for the salvation of the world, for the salvation of all, to deliver us from the “present evil time” (cf. Gal. 1.4). The Lord’s prayer to His Father for us can only be heard (cf. Heb. 7.24-25).

The Lord Jesus draws nearer with every moment. He comes back to give us back what once time took away from us. And in the feeling of Christmas anticipation in the New Year – but every real event and date, ecclesiastical or secular, is an Easter event – we call on Him to return.

Therefore, on New Year’s Eve, together with the whole Church, and thus with all who have left us but retain their voice in Christ Jesus, the whole world cries out in the words of the Apocalypse: “Hey, come, Lord Jesus! show us the clear river of the water of life!” (Rev. 22,20).