The daughter of the crowned imperial couple of Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna simply signed her paintings – “Olga”

Nadia Knudsen, journalist, International Press Centre, Copenhagen

Olga Alexandrovna Romanova, the younger sister of the last Russian Tsar Nicholas II, was a renowned artist whose talent shone with love for Russia, where she lived half her life in the status of a princess.

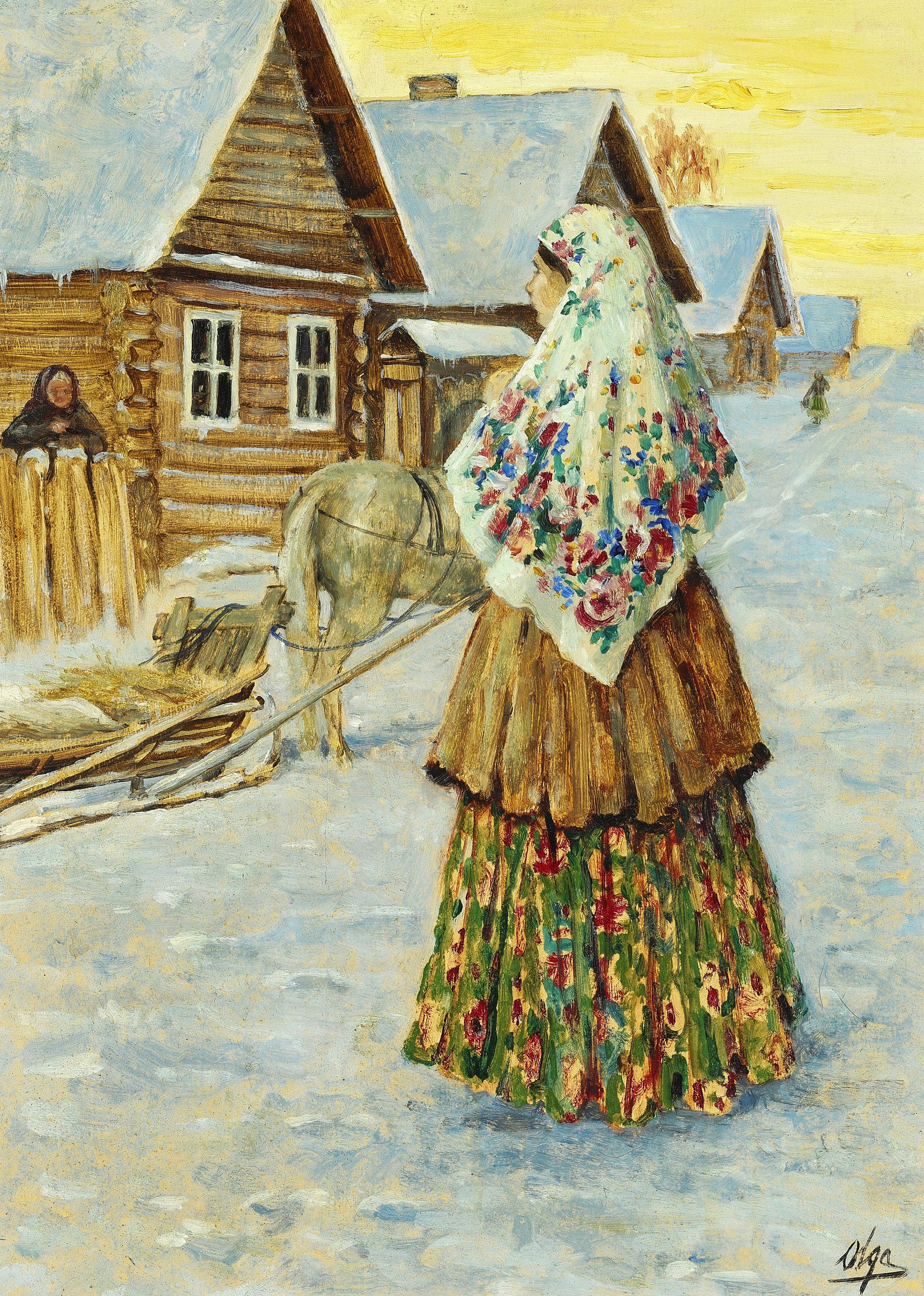

The daughter of the crowned imperial couple of Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna simply signed her paintings – “Olga”. And now, for almost a century, her works, intense but subtle in the manner of execution, have been decorating the palaces and castles of the royal families of Europe in Great Britain, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.

The gift of drawing was discovered in Princess Olga in early childhood by one of the private tutors, the Englishman Charles Heath, who drew attention to the little girl’s passion for watercolour drawing, the art of which he himself was excellent at.

Such famous artists as Vladimir Makovsky and Sergei Vinogradov were invited to the country palace from the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg to teach her painting, and the courtier master of painting Stanislav Zhukovsky, known for his magnificent portraits, palace interiors and marvelous beauty landscapes, taught the very basics to young Olga.

Later, in her diary entries, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna recalled: “I did not part with a pencil for a minute, I remember that I always had it in my hand, but it was like that for everyone in our family, almost everyone had a talent for drawing. My younger brother Misha was distinguished by this, he drew very well, and with his left hand, my sister Xenia also could draw. And we had someone to inherit it from: our mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, in the first years of her marriage in 1866, painted a lot – both paintings and watercolours, but later the children more than filled this niche.”

So, the artistic talent did not come to her from strangers. Moreover, in the very family of her mother, nee Princess Dagmar of Denmark, there was someone to learn this skill from. The wife of her younger brother Prince Valdemar, the Frenchwoman Marie of Orléans, was also a recognised artist. The family of Emperor Alexander III liked to visit their palace, coming to Denmark for a couple of months to visit the relatives of Empress Maria Feodorovna. It was kind of a tradition.

After the death of Alexander III in 1894, Maria Feodorovna with her children Olga and Mikhail spent summer vacations at the Bernstorff Palace, the residence of the royal couple of Christian IX and Louise on the seashore, eight kilometers from Copenhagen. And Olga loved to visit her uncle Prince Valdemar in a cosy cottage Bernstorff Slot every day, just half a mile away. Here is how she wrote about it in her diaries: “I always got inspiration there: dear Aunt Marie, a Frenchwoman, often sat in the garden drawing room at the easel and painted. Usually artists don’t like having someone stand behind them when they are working, but for one reason or another, I was allowed to, and I learned a lot from her during those sessions. Aunt Marie loved to paint still lifes, and for their motifs we collected whole baskets of mushrooms, wild berries and flowers, setting off together in the early morning to the closest forest on a donkey cart, and then after the lunch we arranged the composition. And first of all, we picked all the best from our baskets, not allowing to carry our baskets directly to the kitchen.”

The passion for drawing did not leave the Grand Duchess even during the First World War, when she worked as a nurse in a field hospital.

In 1901, Olga married Duke Peter of Oldenburg, but the marriage was unhappy and ended in divorce in 1916. And soon Olga Alexandrovna married the love of her youth, Nikolai Kulikovsky, captain of the Blue Cuirassier Guards.

After the revolution and the escape from the Crimea, where the Romanov family members and the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna were held under house arrest, the young Kulikovsky couple with their one-year-old son Tikhon managed to move to the Kuban, to the quiet village of Novominskaya, where their second son Guri was soon born, and it would seem that happiness settled with them forever. But the fire of the Civil War was getting closer and closer, the Kulikovsky family managed to escape to Novorossiysk and later in April 1920, with the support of the Danish consul Thomas Schütte, they reached Denmark, where the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna had emigrated a year earlier.

And it was there, in the calm Kingdom of Denmark, that seven years later the first solo exhibition of paintings by Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna took place.

The Grand Duchess, with her two sons and her husband Nikolai Kulikovsky, lived in Hvidøre Palace on the seaside under the caring wing of her mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. And from the very first days of her life in Denmark, Olga Alexandrovna renewed her contacts and acquaintances with recognised masters of painting. One of them was the famous artist Peder Mønsted (1859– 1941), who back in the day painted a portrait of her father, Emperor Alexander III.

According to experts, Mønsted’s influence is seen in many paintings of Olga Alexandrovna, especially in her favourite motifs of the Danish province with straw-covered peasant houses. She valued his advice and often went out with him to paint nature, since the neighbourhoods around the palace were incredibly picturesque. At first she painted a lot of watercolours, later she began to paint in oils.

In her letter to Madame Brizak sent to Paris on February 2/15, 1928, she wrote: “Now I am again enthusiastically working on my watercolours – I am painting Crimean things! I have a few sketches here, and I combine them, arrange them, and I find it so interesting that the days are too short for me… At 8½ I can start, but at 4 P.M. I can no longer work – I have a lot of other duties to perform… My heart is with you. Olga.”

The first successful exhibition of the Grand Duchess’ work in January 1927, held at the Free Artists Gallery in the center of Copenhagen, was followed by the second successful exhibition in 1929, where most of her artworks were sold out in the first days.

In her essays, the Grand Duchess called life at the Knudsminde estate, bought by inheritance after her mother Maria Feodorovna who passed away in the fall of 1928, “the happiest and most fateful period that lasted eighteen years”. It must be noted, that it was, perhaps, the most productive period in her creative life. It was here, among the picturesque meadows, fields, forest lakes, beech groves and murmuring streams, where she went in the morning, taking with her an easel and her little granddaughter Xenia, daughter of her youngest son Guri. She painted a lot, being fascinated by nature, which gave her endless inspiration.

After all, her sons grew up, and the Knudsminde estate itself, where cows, horses, piglets, chickens, ducks and geese were kept on farms, and the fields were sown with wheat, rye and sugar beet, was run by the Cossack Shisko, the main housekeeper and household retainer Gelevka and, of course, Nikolai Kulikovsky, who descended from the Don Cossacks and bred riding horses on the estate, because he knew a lot about it.

And the dear princess, as her Danish acquaintances affectionately called her, could now devote all of herself to creativity. The Grand Duchess also showed a talent for painting on porcelain, and she was invited to the Royal Danish Porcelain Factory. Later she painted her favourite motif – aconites, snowdrops and anemones, those early spring flowers of the Danish copses – on a tea set of wondrous beauty for Thomas Bavaria. And for a decent reward.

Olga Alexandrovna also gave porcelain painting lessons at courses in the city of Ballerup, which generated her income. And she was very proud that she could contribute to the family budget.

In the meantime, Olga Alexandrovna’s paintings were successfully exhibited and were in great demand at exhibitions and sales. The Grand Duchess developed a particularly good relationship with Richard Petersen, the owner of the gallery at Gammel Strand 46. Even after emigrating to Canada in 1948, she continued to use his services. Olga Alexandrovna’s works were exhibited in 1953, 1956, 1958 and 1959 in the halls of the gallery, which was located at that time opposite the parliament building in the center of Copenhagen.

And the biggest success was at a major charity exhibition organised in 1936 in London in favour of Russian refugees. Then all 50 paintings of the august artist were sold out in two days. The buyers of her paintings included Queen Mary of Teck, the wife of King George V, Queen Maud of Norway, Baron Rothschild, Cecil Beaton and the Churchill family.

By the way, in addition to ten major exhibitions of her paintings in the galleries and halls of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna always participated in charitable Christmas markets held in the luxurious halls of the Odd Fellow Palace, where the royal couple of the Danish ruling monarchs certainly visited. This good tradition was established during the lifetime of the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna: Christmas markets were held in Copenhagen under the auspices of the Russian Charitable Committee, becoming the event of the year. The proceeds went to support Russian refugees and needy emigrants.

Looking at the works of Olga Alexandrovna, whether they are radiant bright watercolours with an Easter Russian festive table or winter landscapes with birch trees near a rural church, you are immediately imbued with the quivering love of the artist that shines in them. And you wonder, where the Tsar’s daughter, who grew up in the elegance and luxury of the magnificent imperial palaces of St. Petersburg, has it from? I find the answer in her diaries published in Denmark:

“In my first marriage, when I was married not for love to the Prince of Oldenburg at the age of 19 and a half, I was satisfied that the 33-year-old prince was not foreign, and I did not have to leave my homeland. Although, having lived together for many years, never once we were husband and wife, it was not easy to get a divorce. And therefore, from the very beginning, I tried to spend a lot of time on his family estate, the Ramon estate, which is 40 km from Voronezh. Surrounded by forests and villages, it was incredibly beautiful, I often went for a walk, immediately made friends with the family of a local village doctor, of my age, who gave me the opportunity to learn the basics of medicine and later become a nurse in a Red Cross hospital.

In the villages nearby, I saw simple Russian peasants, who lived in such need and poverty that I could not even imagine. But at the same time, they had so much kindness, greatness of soul and unshakable faith in God, which helped them to fight difficulties and enjoy the simple joys of rural life! In my eyes, they were very poor people, but incredibly rich spiritually, next to them I discovered real values in myself, too.”

All this and love for Russia helped Olga Alexandrovna overcome many difficulties that befell to her lot.

The fate of the Grand Duchess was such that she and her husband Nikolai Kulikovsky had to emigrate to Toronto, Canada, after living 28 years in Denmark. And not alone, but with the families of their then adult sons, with Danish daughters-in-law Agnetta and Ruth, with grandchildren Xenia and Leonid. Having first settled down as a large family in a house on the shores of Lake Ontario, the Grand Duchess, to whom the nature of Canada was very reminiscent of Russia, still had her art brushes in her hand at 66 years old.

In 1955, she entered a competition to design new postage stamps, and her design of soft blue anemones was selected for the 10-cent stamp.

Olga Alexandrovna was very fond of giving to friends and acquaintances, especially for Christmas, her small watercolours designed as postcards at a printing house.

In her letter to Danish friend Wilhelmina Christensen sent to Denmark on February 2, 1959, Olga Alexandrovna wrote: “I have just returned from the forest, where I was sitting the day before – right on the snow, in the middle of the forest edge, – it is so wonderful to draw these blue shadows from the trees, I didn’t feel the cold at all!”

Iconography was also one of the passions of the Grand Duchess, but she never sold her icons, but only gave them away. In 1920, she created her first icon with the face of St. George the Victorious, who on a white horse pierces a dragon with a spear, and presented such icon to the priest A. Chepurdyaev, the then rector of the Orthodox Church of St. Alexander Nevsky in Copenhagen (now it is kept in one of the Danish museums).

Being a deeply religious person, like everyone else in the Romanov imperial family, immediately after moving to Canada on May 21, 1948, Olga Alexandrovna became a parishioner of the Russian Orthodox Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Toronto, where she subsequently painted part of the iconostasis (the second row with the prophets), and created the icon of the Mother of God as a gift to the cathedral. All these are preserved in the temple to this day. Later, the Russian school at this church was named Grand Duchess Olga Aleksandrovna Parish Russian School – in honour of the Grand Duchess.

But the years took their toll… In a letter to same Wilhelmina dated October 17, 1957, the Grand Duchess wrote: “I still draw a lot, but like everything that I do now, it goes slowly.”

Olga Alexandrovna passed away on November 24, 1960, two years after the death of her husband Nikolai Kulikovsky, with whom they lived together for 42 years in love and happiness.

And her paintings, more than 300 of which are now kept in private and museum collections, and about 1000 watercolours spread over the world, which are so simple and at the same time marvelous, imbued with kindness and tranquility, – preserve her love for Russia, which did not leave Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna until the very last minute of her life. As the historian Yevgeny Pletnev noted in his study: “What attracts in the creative manner of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna is the naturalness of nature in all its simplicity, behind which one can easily guess the inner grace and aristocracy and spiritual wealth, which, however, was characteristic of the most august artist from the Imperial House of Romanov. Lovely rural landscapes, flowers and animals, sketches of home interiors and Christmas trees on the estate, churches in the Russian outback, simple genre scenes of rural life, winter festivities and faces of pre-revolutionary Rus’ – the very world of her creativity, where everything is filled with kindness, tranquility and spirituality . And it is no coincidence that the last picture of the Grand Duchess, who was a deeply Orthodox person and believer, was a watercolour with an Easter festive table – as a symbol of her faith in resurrection, in eternal life.”

It is not surprising, that interest in the paintings of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna continues to grow. Over the past three decades, their geographical range has also expanded from the USA to Sweden and Finland, and in Russia – from Moscow to Yekaterinburg.

In Russia, where interest in the work of the august artist has especially increased, major exhibitions of her works were held in 2007 and 2013. The 2013 exhibition was dedicated to the 400th anniversary of the Imperial House of Romanov. It also took place in the UK, France, Germany, and Canada.

And in Denmark, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the largest Danish auction house, Bruun Rasmussen, the jubilee Russian auctions were organised on November 30, 2018, which became a real firework of the Russian creative heritage – from the works of Carl Faberge and the sapphire diadem donated in 1898 by the Russian Tsar Nicholas II for the wedding of the Crown Prince Christian (X) of Denmark with Crown Princess Alexandrine, to the paintings of K. Korovin, I. Repin, A. Makovsky, P. Vereshchagin, V. Polenov…

It is worth noting that these Russian auctions opened with three works by Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna: Home, Winter Day in a Russian village with a woman in a colourful dress and The Russian tea table at Knudsminde. On them are village festivities and girls with faces reddened from frost, and a plot from life on the Knudsminde estate dear to the artist’s heart: a tea table with a pot-bellied samovar, which, with its brilliance, could compete with the imperial diadem and Faberge jewelry.