Russian classics on the Nativity of Christ and the celebration of New Year’s Eve

By Kirill Privalov

«Every year ends happily – it ends with a New Year.» I don’t remember where or when I heard this, but there is some truth in this expression. That’s right: isn’t every New Year, combined with Christmas, the best present from God for us? Even if it is not filled with childishly anticipated naive joy, even if it is painted in alarmingly sad colours, and even if it is associated with a foreboding of gloomy anxiety?… As in the works of Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov-Shchedrin.

My mention of this wonderful Russian satirical writer in the New Year’s context is no coincidence. This year marks the 200th anniversary of his birth. In my judgement, Saltykov-Shchedrin is a true literary phenomenon: the more you read his works, the more keenly you feel that he has not yet been fully understood by posterity and that his prophecies have not yet fully come true.

Saltykov-Shchedrin’s mention of the New Year is not a mere artistic sketch, but an occasion for truly philosophical reflection: «In effect, what is the ‘old year’ and what is the ‘new year’? Has humanity not yet learned enough from experience to make sure that these are nothing but terms with an exclusively astronomical meaning? And why should we, simple and poor people, care about what happens in the sphere of astronomy! Does the ‘new year’ bring us pies and roast pork? Does the ‘old year’ take away into eternity all the staleness this vale of tears is dotted with? What do we rejoice in? What do we regret? Oh, let’s leave astronomers alone to prove everything they are supposed to prove, and let’s live as we live, hiding nothing from ourselves, but not exaggerating anything either.

“Life was good in the old year, and it will be good in the new one. It’s just the way it was originally designed: always to live exactly the way you live…»

You cannot disagree with such a confession. It is from his notes, Our Social Life, from January 1864. And in The Provincial Sketches of 1857, in a sketch under the characteristic title The Christmas Tree, Saltykov-Shchedrin gives a whole panorama of Russian provincial life just before the Nativity: «It’s very cold outside; the frost has firmly frozen over and smoothed the road, and now it’s knocking on the doors and windows of ordinary inhabitants of Krutogorsk with all its might. Evening has set in, and the streets are deserted and quiet. The moon is looking down from its great heights genially and cheerfully and is shining out so clearly that it’s like a day in the streets. A small horse is running in the distance, briskly carrying a sledge with a provincial aristocrat sitting in it, hurrying to a party, with the rumble of its hooves heard far away. Lights are lit in the windows of most of the houses, which at first are dim, and then gradually turn into magnificent illuminations. Walking down the street and peering through the windows, I see whole beams of light, around which lovely children’s heads are hurrying and scurrying back and forth… ‘Oh, it’s Christmas Eve today!’ I exclaim in my mind.

“Enlightenment is steadily penetrating eastwards, thanks to the zeal of our dear government officials who have girded themselves to fight against barbarism and benightedness. I don’t know if there is a Christmas tree in Turukhansk, but in Krutogorsk it is generally respected – this is an undoubted fact. At least, officials who breed like rabbits in Krutogorsk consider it their indispensable duty to buy Christmas trees at the market and, decorating them with simple homemade ornaments, present them to numerous young Ivans and Marias…»

It seems very interesting to me to recall what Russian classics of different times and places of residence wrote about the Nativity of Christ and the celebration of New Year’s Eve. And not only directly in their works, but also in letters to people close to them.

«In my view, to rejoice in such nonsense as the New Year is ridiculous and unworthy of human reason,» Anton Chekhov argued in the short story, A Night at the Cemetery, published in 1886. “The new year is just as bad as the old one, with the only difference that the old year was bad, and the new one is always worse… To my mind, when celebrating New Year’s Eve, one should not rejoice, but suffer, weep, and attempt to commit suicide. We must not forget that the newer the year, the closer to our death, the larger our bald spot, the deeper our wrinkles, the older our wives, the more the children, and the less the money.»

Caustic and merciless in his words, Anton Pavlovich remained true to himself even during the “magical” – just not for him! – New Year’s Eve. Chekhov did not change in his postal holiday greetings either. Here is what he wrote on 27 December 1897 to Lika (Lydia Mizinova), a person close to him: «Now it’s New Year’s Eve in Moscow and new happiness. Greetings! I wish you all the best, good health, money, a husband with a moustache and a great mood. With your bad temper, keeping high spirits is as necessary as the breath of life, otherwise your workshop will get the stuffing knocked out of it.»

Anton Pavlovich also wittily greeted his older brother Alexander in a letter dated 2 January 1889. His common-law wife, Anna Khrushcheva-Sokolnikova, had died the previous year. Alexander, also a man of letters, was not a widower for long and married his sons’ governess Natalia Golden (the future mother of Mikhail Chekhov, a brilliant actor and theatre director). Here is the New Year message:

«Wise gentleman!

I wish your radiant lady and children a Happy New Year and new happiness. I wish you to win 200,000 and become an active state councillor, and most of all, to be in good health and have daily bread in sufficient quantity for such a greedy-guts like you…

«The whole family says hello to you.»

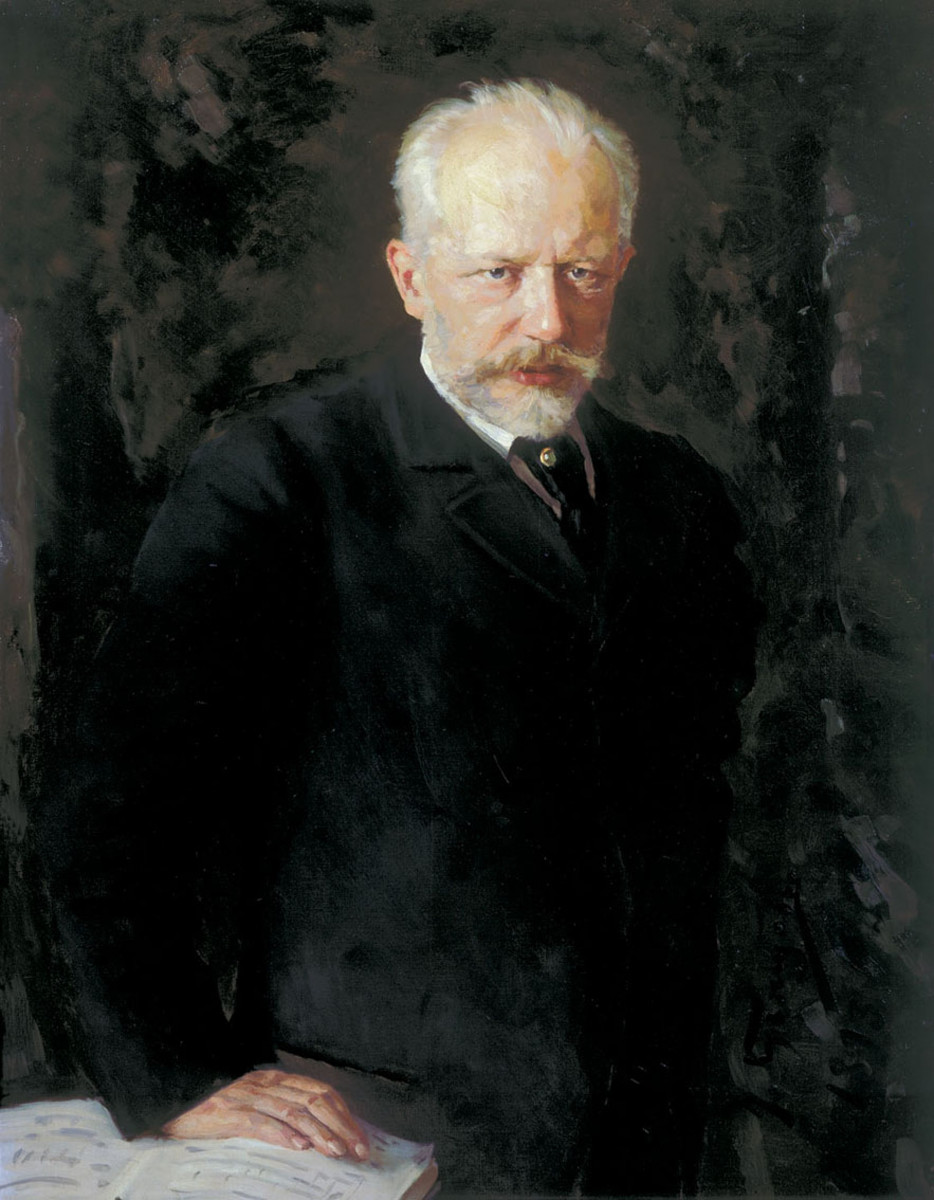

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s New Year greetings are in the epistolary genre as well. On 2 January 1880 he wrote to the philanthropist and patroness of arts Nadezhda von Meck, who for many years supported him with a sizeable sum of 6,000 roubles a year. The «beautiful stranger» (Tchaikovsky and von Meck never met in person) to whom the grateful composer repeatedly confessed: «Your friendship will always be the great joy of my life.» Celebrating Catholic Christmas in Rome with his younger brother Modest, Tchaikovsky sent his New Year greetings to the von Mecks’ estate in Brailov in what is now Ukraine:

«We celebrated New Year’s Eve with books in our hands. In my mind, my dear friend, I wished you all the best on earth: firstly, of course, good health; secondly, success in your work, and especially your estate in Brailov finally to get onto a solid footing; thirdly, to avoid any troubles and adversities this time if you travel abroad; fourthly, wished everyone close to your heart to be happy and satisfied. Looking back on the past year, I must sing a hymn of gratitude to fate for the many good days I have lived both in Russia and abroad. I can say that over the whole year I enjoyed undisturbed well-being and was as happy as happiness can be. Of course, there were bitter moments, but these were only minutes, and even then, I was just affected by the hardships of those close to me, and I myself was certainly happy and content. It was the first year of my life when I was free all the time. And I am indebted for all this to none but you, Nadezhda Philaretovna! I invoke all the fullness of blessings on earth upon you.»

The Russian New Year was also described from Paris by the wonderful emigrant writer Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya (penname: Teffi). In her short story, The Neighbour, she compares the French Peer Noel and the Russian Father Frost, and far from favouring the Frenchman: «In front of the pastry shop, a costumed Peer Noel walked along the pavement with a Christmas tree in his hands. The children shouted their wishes to him. Their mothers nodded their heads as they listened, but they had nothing to do with it. Peer Noel remembers everything himself: who wants what. The neighbour dared not shout out his wishes. Besides, there were so many of them that he wouldn’t have made it anyway. He wanted everything that other children asked for, and besides, all those peculiar things that the Russians had. But, of course, he was suffering because he hadn’t had the courage to ask. And he was very unhappy. It was good that Katya kindly wrote to the Russian Father Frost that evening. He will bring everything he can take along. He is unlikely to take a model railway the neighbour requested for, but it’s not hard to bring a drum. And he’ll probably take a wonderful brilliantine-bottle, too. In short, life will be even more fantastic.»

And here is how Lydia Alexeyevna Charskaya, rightly nicknamed by her contemporaries «the dominant influence of Russian high school girls», describes the festive evening at the Pavlovsky Institute for Noble Maidens in one of the bestsellers of the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Notes of an Institute Girl: «In the middle of the hall, all shining with countless candle lights and expensive, shiny ornaments, there was a large Christmas tree up to the ceiling. The gilded flowers and stars at its very top burned and shimmered just like candles. Hanging bonbonnieres, tangerines, apples and flowers made by the grown-ups stood out by their beauty against the dark velvet background of greenery. There were piles of cotton wool under the tree, representing snowdrifts.»

That’s not all. There is a whole Christmas story by Lydia Charskaya (there was such a literary genre) entitled, A Christmas Tree 100 Years Later, published by the Zadushevnoye Slovo (“Heartfelt Word”) children’s magazine in 1915: «… At the same moment, the doors of the living-room opened, and Marsik screamed with delight and surprise. There was a fabulous Christmas tree in the middle of the room. Toys and sweets were hung on it, and on each twig a tiny flashlight a little bigger than pea sparkled brightly.

«The tree shone all over like the sun in southern countries. At this time a large box in the corner started playing. It wasn’t a gramophone, but some other musical instrument. It seemed as if a wondrous chorus of angelic voices was singing the song of the night in Bethlehem when the Saviour was born.

«‘Glory to God in the Highest and on earth peace, good will toward men,’ sang beautiful angelic voices, filling the room with their wondrous sounds.»

The remarkable Soviet author Lev Kassil recalls New Year’s Eve in an absolutely different way, much more restrained and modest, in his book, Conduit and Schwambrania, which brought up several generations of «builders of Communism» in the USSR. Kassil’s New Year’s Eve is, alas, a special occasion for adults only: «31 December came. By nightfall, our parents had gone to celebrate New Year’s Eve with their friends. Mum explained to us for a long time before leaving that ‘New Year’s Eve is not a children’s holiday at all and you must go to bed at ten, as always.’»

How deplorable! It’s tempting to recall an old saying: «It’s good to make money in an unfamiliar place, but it’s good to celebrate New Year’s Eve in a familiar one.» With meaningful toasts, inspiring copious drinks with sumptuous (preferably «hot, Moscow” ones, as Mikhail Bulgakov advised) snacks.

By the way, toasts could well be borrowed from Russian classics – for instance, Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin: «Love is the only game in which an amateur has a better chance of perfection than a professional.»

All that remains is to add: «Let’s drink to love and to perfect lovers!» Or from Fyodor Dostoevsky: «You must love life more than the meaning of life.» We have only to reply in kind: «Let’s drink to real life!» – and a resounding toast is ready for everyone at the hospitable table!…

A list of tips from the grandees of Russian literature for masters of toasts (what a wonderful Russo-Caucasian profession!) can go on and on… However, you and I now have a goal other than encouraging new gluttonous exploits in the lovers of New Year’s Eve. And the author’s task is to continue the narrative of the New Year celebrations in olden days with the help of classics of Russian literature. For example, Alexander Ivanovich Kuprin.

«I remember a Christmas tree well from my childhood: its dark greenery through the dazzling mottled light, the sparkle and glitter of decorations, the warm glow of paraffin candles, and especially the smells,» Kuprin writes in his short story, The Little Christmas Tree. “How pungent, cheerful and resinous the suddenly illuminated needles smelled! And when the tree was being brought in from outside, with difficulty pushed through the open doors and curtains, it smelled of watermelon, forest and mice. Our cat with a pipe-like tail was very fond of this mousy smell. In the morning, it could always be found deep in the lower branches: for a long time, it sniffed the trunk suspiciously and carefully, poking its nose into the sharp needles: ‘Where is a mouse hiding here?’ As a candle burns down, it sends out a long, swaying flame and its sooty smoke is fragrant with memory, too.

“Our toys were marvellous, but someone else’s always seemed better. Clutching the present you’ve received to your chest with both hands, at first you don’t look at it at all: instead, you seriously, silently, and frowningly look at the toy of your closest neighbour. <…>

“What can I say? The Christmas tree is enchanting and intoxicating. It is intoxicating, because from the multitude of lights, from strong impressions, from the lateness of the hour, from the long bustle, from the hubbub, laughter and heat, the children are drunk without wine, and their cheeks are of a red calico colour.

“Oh, how much grown-ups get in our way! They don’t know how to play themselves, but they still fuss around with some round dances, songs, caps, and games. We’ll do just fine without them! And then there’s Uncle Pyotr with a goatee and a reedy voice. He seated himself on the floor under the Christmas tree, sat the children around and started telling them a fairy tale. Not real, but one that he had thought up. Oh, what a bore, even to the point of disgust! The nanny knows a true fairy-tale.»

If we take into account that the New Year is inseparable from Christmas, we can also recall angels. It’s little wonder that one of Leonid Andreyev’s short stories is entitled The Little Angel:

«…With their little eyes wide open in advance and holding their breath, the children decorously, in pairs, entered the brightly lit hall and walked quietly round the sparkling Christmas tree. It cast a strong light, without shadows, on their faces with little staring eyes and lips. For a minute there was the silence of deep charm, followed by a chorus of enthusiastic exclamations. One of the girls was unable to control her delight and jumped on the spot stubbornly and silently; a small pigtail with a plaited blue ribbon bounced on her shoulders. Sashka [a diminutive of the name Alexander]was sullen and sad – something bad was going on in his small, wounded heart. The Christmas tree dazzled him with its beauty and the flashy, cheeky glare of countless candles, but it was alien and hostile to him, like the neat, beautiful children crowding around it, and he wanted to push it so that it would fall onto those fair heads. It was as if someone’s iron hands had taken his heart and were squeezing the last drop of blood out of it. Hiding behind the piano, Sashka sat there in the corner, unconsciously finishing breaking the last cigarettes in his pocket and thinking that he had a father, a mother, and his own house, but it appeared as if none of this existed, and he had nowhere to go. He tried to imagine a penknife that he had recently traded for and loved very much, but it had become very bad, with a thin, sharpened blade and only half a yellow handle. Tomorrow he will break the knife, and then he will have nothing left.

“But suddenly Sashka’s narrow eyes flashed with amazement, and his face instantly assumed its usual expression of cheek and self-confidence. On the side of the tree facing him, which was dimmer than the others, he saw what was missing in the picture of his life and without which everything was so empty, as if the people around him were artificial. It was a small wax angel, carelessly hung in the midst of dark branches and seemed to float through the air. Its transparent dragonfly-like wings fluttered from the light falling on them, and it seemed very alive and ready to fly away. Its pink hands with delicately made fingers stretched upward, and behind them a head with hair like Kolya’s. But there was something else in it that Kolya’s face and all other faces and things lacked. The angel’s face did not shine with joy, was not gloomy with sadness, but it bore the stamp of a different feeling, which cannot be conveyed by words or defined by thought but is accessible only to the same feeling. Sashka could not grasp what secret power drew him to the angel, but he felt as if he had always known it and always loved it, loved it more than his penknife, more than his father, and more than everything else. Full of bewilderment, anxiety, and incomprehensible delight, Sashka folded his arms by his chest and kept whispering:

‘Dear… dear little angel!’»

«What shall we offer Thee, O Christ,

Who for our sakes hast appeared on earth as man?..» reads one of the first stichera, sung at the beginning of Vespers of Christmas Eve. How can we not turn to Vasily Rozanov’s essay entitled, Merry Christmas! after that? There is no sin in concluding in his pure, high-pitched tone:

«Once again, the Eternal Infant is being born in the consciousness and feelings of people; He is being born in a manger – that is, in a cave where Syrian shepherds would drive their flocks at night, protecting them from predators. Again, first the shepherds of the surrounding flocks are coming to bow down before the Infant and God; and then the /Magi from the East/ will bring Him gifts – gold and incense – that signify both the priestly and royal ministry of the Newborn Infant. Thus, in these features, both simple and folk, saying something /native/ and /dear/ to every poor hut – and together in the Heavenly and religious features, foretelling the future ringing of bells of Christian churches – our Christ was born, Who taught people and the nations a new truth – the One Who would proclaim to everyone that a new law of grace-filled existence was born.

“The Nativity of Christ conveys what is /native/ and /dear/ to every hut. No kingdoms and no authorities, no extensive and new laws that require man to obey and speak to him in the language of command, would ever have brought that inner content and heartfelt speech, which the Newborn Infant gave to people. <…>

«May God be with you! Greetings to everyone, remember the poor and give them something for the feast! And don’t forget God and ingenuous Russian gaiety.»