True holidays are not alone

By Augustine Sokolovski, Doctor of Theology, Priest

The date of the celebration of Christmas is linked to a belief that was widespread among the biblical people during the earthly life of Jesus Christ. It was a time of universal expectation of the Messiah. The Bible consists of many books. They reflect vast periods of time. The history of the Bible is the history of the Covenant between God and man. God has always been faithful to this Covenant, but man, represented by God’s people, has constantly been unfaithful and broken the Covenant. God sent leaders and helpers to ancient Israel who delivered them from the disasters, captivity, and catastrophes into which the people had plunged themselves through their own fault.

As the birth of Jesus drew near, there was a growing conviction that such a helper and deliverer was soon to come, who would once and for all, in the most decisive manner, rescue the people from all their misfortunes. It was He who was destined to become the true Anointed One of God, the one and only Messiah in Heaven and on Earth. The circumstances of His earthly life were to be not only unusual but also surrounded by supernatural events. The life of the Messiah simply had to be woven from a multitude of unique and unrepeatable coincidences. One such great coincidence was the predestination that the Messiah would die on the day of His conception.

There are corresponding prophecies about this in the biblical text. “Do no cook a young goat in its mother’s milk”, — it is said in the Book of Exodus (Chapter 23, verse 19). This prohibition proved to be so important that it is repeated in the Book of Deuteronomy, which, according to scholars, formed the basis of the Israeli Constitution during the religious revival on the eve of the Babylonian Captivity. Here is what is said in verse 21 of chapter 14 of this book: “You are a people holy to the Lord your God. Do not cook a young goat in its mother’s milk”. These words are so mysterious, so closely tied to the context of the time in which they were formulated, that it took the experience of the Church and the wisdom of the Holy Fathers to give even an approximate interpretation.

“Since Christ did not suffer in childhood when Herod sought to kill him and it seemed that such danger hung over him, a prediction was made with the following words: “Do not boil a kid in its mother’s milk.” Christ suffered like a lamb boiled in its mother’s milk, that is, at the time of his conception, and that Christ was conceived and suffered in that month, as evidenced not only by the celebration of Easter, but also by the day of his birth, well known to the Churches. He who was born nine months later, around December 25, was conceived, apparently, around March 25, which was also the time of his suffering in his mother’s milk,» is how St. Augustine (354–430), a great Father of the Church, interprets these words of Scripture in one of his little-known but very important works, whose title literally translates as “Questions on the Seven Books,” that is, the first seven Books of Scripture (Quaestionum in Heptateuchum 2; 90). The date of March 25, mentioned by Augustine and celebrated as the Feast of the Annunciation, was calculated astronomically, as it is linked to the celebration of the Jewish Passover in the year of Jesus’ crucifixion. It is this date that determines the date of Christmas.

This testimony of St. Augustine is extremely important. After all, the Church Fathers did not usually engage in historical research in liturgical matters. They celebrated events that were customary to celebrate in their local churches. During the era of the first Ecumenical Councils, there was great diversity, with churches and even individual dioceses often using their own Eucharistic prayers and even Creeds. The unification of these matters came later and is associated with the split of Eastern Christianity into two parts, Orthodox and Monophysite, and, of course, with the emergence and spread of Islam.

To conclude the biblical theme, let us note that the prophecy from Exodus and Deuteronomy was not the only one. In the Book of Job, which presents the image of a suffering righteous man in whom Christians saw Christ the Messiah, Job himself curses the day he was conceived. The third chapter of this great biblical book, the mystical Old Testament “Gospel of Suffering,” begins with the words: “Then Job opened his mouth and cursed the day of his birth. And Job began and said: ‘Let the day perish on which I was born, and the night when it was said, “A man is conceived!»’ (Chapter 3, verses 1–3). According to ancient exegetes, among whom the Church Fathers hold a special place in Orthodoxy, these words are also connected with the biblical predestination of the Annunciation, Nativity, and Crucifixion of Jesus.

The early Christians called the dates of the martyrdom of the saints their birthdays. The word “martyr” in Greek literally means “witness.” “These are the words of the Amen, the Faithful and True Witness, the Ruler of God’s creation,” says the Apocalypse (Revelation 3:14). From these words, it is clear that the first martyr, the true witness, was the Lord Jesus. The first three centuries of Christian history, from Easter and the Descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles to the sole reign of Constantine (324), were a time of persecution by pagans. Martyrs suffered for bearing witness to their faith, believing that their death was not destruction, but birth in Jesus. In his Epistle to the Corinthians, the Apostle Paul calls Jesus “the firstborn from the dead” (1 Corinthians 15:20). From the perspective of the first Christian generations, the day of the Lord’s crucifixion was His birthday. It took three centuries before, with the end of persecution and the beginning of the universal spread of the Church, Christians realized through the Holy Spirit that it was necessary to truly assimilate the Gospel accounts of the Savior’s birth into the world and solemnly celebrate the Nativity of Jesus.

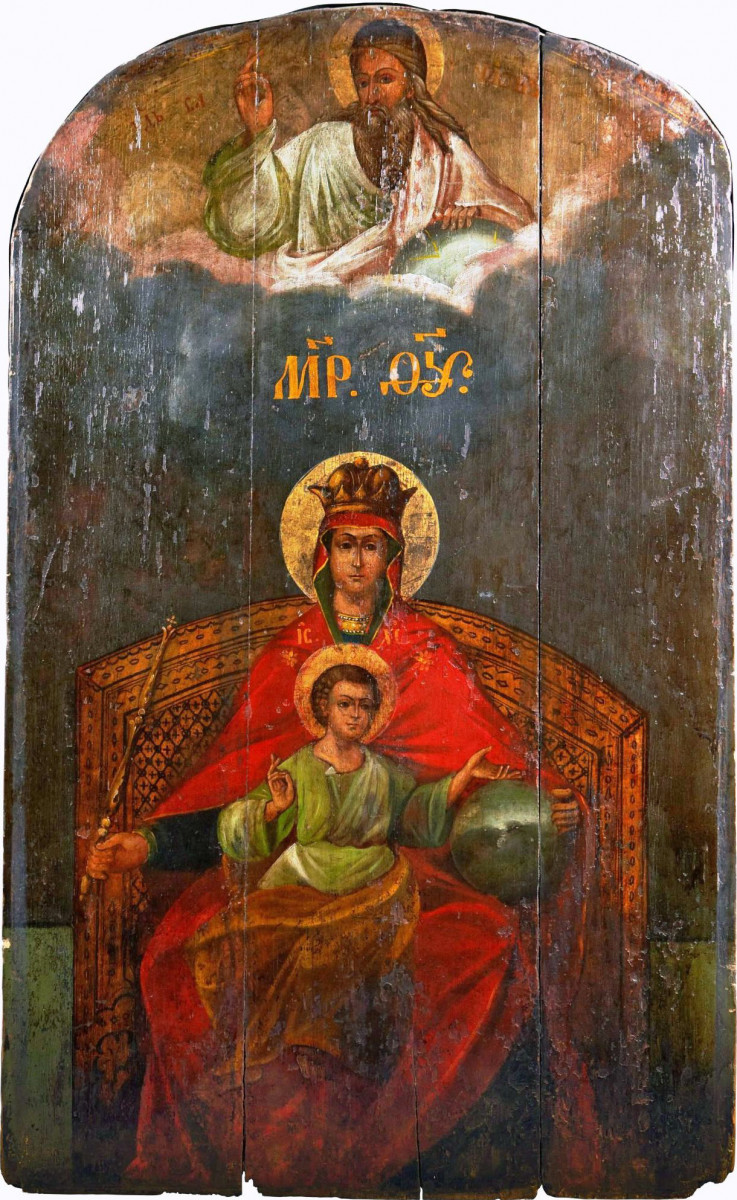

Easter has been celebrated by Christians since the very beginning. Other holidays came later, spreading throughout the Christian world with the end of persecution. Over the centuries, a process that took a very long time, a higher register of holidays was formed in the Orthodox liturgical calendar, twelve in total, which to this day are invariably and solemnly celebrated by the Church. They are called the “twelve great feasts.” All of them are dedicated to Christ or the Mother of God, or to Christ and the Mother of God together. Easter, being the basis of all these celebrations and immeasurably higher in significance, is not included in this number. On the twelfth day after the birth of Christ, the Church celebrates the feast of the Epiphany. In Orthodoxy, this feast is also called the Baptism of the Lord.

Initially, Epiphany was the only major Christian holiday after Easter. While Easter celebrated the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, who ascended into heaven and sat at the right hand of the Father, Epiphany celebrated the Incarnation of God. Epiphany encompassed the entire spectrum of meanings associated with Jesus’ earthly life. Thus, Easter and Epiphany constituted the two poles of the revelation of the New Testament mystery. At a certain point in history, the feast of Epiphany was, in a sense, “divided” into two parts, and Christmas separated from it, just as Eve separated from Adam’s rib. This was the case in the East.

In the Roman Catholic Church, Christmas has been celebrated since ancient times. Currently, in the Christian West, Epiphany primarily symbolizes the worship of the Magi, while in Orthodoxy it symbolizes the baptism of the Lord Jesus, the beginning of His preaching, and the beginning of His earthly ministry. The place of the Epiphany is the world. God loved this world; He will never abandon it. By the power of His glorious Epiphany, He is present in the universe forever. The people of God know that “there is no salvation outside the Church.” In turn, the Church, which loves this world with the love of the Holy Spirit, believes that there is no salvation outside this world created by God.

In 1918, World War I ended. Four years later, following the defeat of the Greek armies, which in turn was caused by the cessation of Allied aid to Greece in the war against Turkey, the entire Greek Orthodox population of Asia Minor was forcibly resettled in Europe. The Patriarch of Constantinople lost his flock. It was a great, apocalyptic upheaval.

In 1924, the Church of Constantinople switched to the modern calendar. Several other Orthodox Churches followed suit. Nowadays, Christmas on December 25 is celebrated by Greek Orthodox Christians, the Patriarchate of Antioch, as well as the Romanian, Bulgarian, and Albanian Orthodox Churches. The Orthodox Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia, as well as the Orthodox Church in America, also belong to this group. The Russian Church, the Serbian Church, the Georgian Church, the Polish Orthodox Church, the Church of Jerusalem, and the Holy Mountain of Athos celebrate Christmas on January 7. The difference of thirteen days exists in this century, and in the next century it would have increased by another day, but the “date change” will not take place because it has been suspended by tacit agreement. The Russian Church celebrates its holidays according to the old calendar, which is called the Julian calendar.

The Gospel story of Christ’s birth has inspired theologians, saints, poets, artists and musicians to create original works of art dedicated to the most important event in human history. One of the central works in the oeuvre of German-language writer Edzard Schaper (1908–1984) is The Legend of the Fourth Magi, in which the fourth wise king turns out to be a Russian prince. Schaper is the author of numerous works of fiction, novels, novellas, and short stories, in which he boldly expresses his position as a writer and Christian, calling for adherence to the Gospel commandments. The writer is best known for his two-part novel The Dying Church (1935) and The Last Christmas (1949), about the life and tragic death of the Orthodox priest Father Seraphim and his community, and about the new hope born in the Church through the suffering of the martyrs. The Legend of the Fourth Magi (1961), which describes in fairy-tale form the journey of a Russian prince going to worship the newborn Christ Child, represents the author’s profound reflection on the fate and destiny of the world, the Church and Russia. The essence of the story is that the “Fourth King”, who turned out to be a Russian prince, learned in time about the impending birth of Jesus. But having spent too much time on gifts, including Russian honey, he gradually gave them away to all those in need. Along the way, he encountered various vicissitudes and was so late that he arrived only at the moment of the Crucifixion.

The legend of Edzard Schaper was undoubtedly inspired by Russian religious thought, as well as by the circumstances of the writer’s own life, who wandered extensively, lived in Estonia, Finland, and Poland, was twice sentenced to death in absentia by a Nazi court, and witnessed the persecution of the Church in various, often contradictory circumstances. How can we not recall the great painting by Russian artist Mikhail Nesterov (1862-1942) “Holy Week,” painted in the tragic 1930s, where the Crucifixion rises against the backdrop of a Russian landscape, before which stand Dostoevsky and Gogol, a priest, and the artist’s wife, who holds a small child’s coffin with the body of their child. The Russian fourth wise king was late, and, like him, the Julian calendar, which is so important for the Russian Church, is also “late” in relation to the “generally accepted Christmas” on December 25.

This “delay” is unique, because it is largely due to this that the outside world, which knows almost nothing about Christianity, can appreciate the stunning, magnificent uniqueness of the Orthodox Christianity. By analogy with the Second Coming of Jesus, which, according to Scripture and dogma, is about to happen but is still on the threshold so that as many people as possible may be saved (cf. 1 Timothy 2:4), the “old-style” Churches, by God’s predestination, “suspend” the beginning of the celebration so that the world may see Orthodoxy in its sovereign beauty. The sovereign is the one who declares a state of emergency and suspends the normal course of events. Like the Fourth Magi, the Russian Church celebrates Christmas with a formal astronomical delay. Thus, believers bow down before the Nativity scene when other Christians, Catholics and Protestants, are already celebrating Epiphany, as the worship of the Magi. In Orthodoxy, the worship of the Magi coincides with the moment of Christmas. The delay does not turn into tardiness, and the Legend of the Fourth Wise Man comes true, but not according to a pre-written script. After all, all Christians still come to the nativity scene together.

In the Symbol of Faith, the Church is referred to as catholic. This term means unity in the greatest possible diversity. Since Eastern Christianity in the fourth and fifth centuries was led by the Church of Alexandria, the custom of celebrating not Christmas but Epiphany has been preserved in the most ancient Orthodox churches, which historically linked their fate precisely to this ancient center of historical Christianity. Therefore, even today, Epiphany is celebrated on January 6 in the Coptic Church of Alexandria and Egypt, the Armenian Apostolic Church, and other ancient Oriental Orthodox Churches. The celebration of the Nativity of Jesus is included here in the single event of the Epiphany; this great tradition does not know a separate holiday of the Nativity of Christ.

In theology, there is a discipline called comparative theology. Its purpose is to identify the differences between Orthodoxy on the one hand, and Catholicism and Protestantism on the other. Another name for this discipline is ecumenical theology. While comparative theology is more polemical in nature, ecumenical theology seeks to find common ground. One of the most common critical arguments in comparative theology is that contrary to the tradition of the Early Church, in Catholicism and Protestantism, the celebration of Christmas has become much more important than Easter. However, if desired, this same argument can be turned around. After all, while formally remaining “only” one of the twelve major holidays, Christmas in Orthodoxy, as in the West, gradually, over a very long process lasting centuries, acquired the characteristics of the “feast of feasts,” as Easter is called in the works of the Church Fathers. This includes the forty-day fast before Christmas, the preparatory weeks, the period of holy days after the holiday during which all fasting is canceled, and finally, the forty-day period leading up to the Feast of the Presentation, which creates an analogy between the period of Easter and Ascension.

However, unlike Holy Week and Easter, Christmas does not cancel the days of commemoration of the saints, which gives the Christmas days special features. On January 5, the eve of Christmas Eve, the Church celebrates the memory of St. Paul of Neocaesarea. He was a bishop, confessor of the faith, and participant in the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (325).

The city of Neocaesarea, with which Paul’s name is associated, was a fortress on the Euphrates. It should be distinguished from another, much more famous Neocaesarea in Anatolia, where, among other great figures of Christian antiquity, Saint Gregory the Wonderworker (+275) was bishop.

The great ancient historian of the Church, Theodoret of Cyrus (393-457), writes that at the sight of Paul and other confessors of the faith who suffered during the Great Persecution of Diocletian at the Council of Nicaea, Emperor Constantine the Great wept. They bore the marks of deep wounds and terrible mutilations inflicted by pagans. Paul himself had his hands burned. Many pagans, especially representatives of the judicial and administrative elite, were not sadists and did not inflict injuries without reason. They heard Christians, primarily bishops, and Paul was such a wandering missionary bishop, refer to the Eucharist in their prayers as “Fire” “Light,” and “the Body and Blood of God.” “Our God is a consuming fire,” says the New Testament Epistle to the Hebrews (12:29).

Driven by vicious curiosity, the pagans decided to test Paul’s words. If he really dared to hold in his hands “the Body of God,” which “is Fire,” would he withstand the test of physical fire? Paul endured and did not renounce his faith. He teaches a lesson to Christians for all time to come.

The words of prayers, especially those addressed to God in the context of the Eucharist and Communion, contain many statements that are astonishing in their boldness. When uttering them, one must be prepared to undergo a test of faithfulness to the words spoken.

When communicating with our brothers and sisters from other Christian denominations, especially Catholics and Protestants, it is important to emphasize that we, Orthodox Christians, truly celebrate the Nativity of Christ. After all, there is a widespread belief among them that Orthodox Christians celebrate only Epiphany. Since about half of Orthodox Christians follow the Julian calendar and the other half follow the Gregorian calendar, it turns out that Christmas in Orthodoxy is not only celebrated twice, on January 7 and December 25, respectively, but, thanks to the Christmastide, that is, the great festive period from Christmas to Epiphany, it lasts almost four weeks, which is practically equal to the time of preparation for Christmas, the sacred Advent.

“Christ is risen!” By analogy with this apostolic greeting of Easter time, with which Orthodox Christians greet each other from Easter to Ascension, during Christmastide it is customary to exclaim: “Christ is born! Glorify Him!”