Russia supported the Government of Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War and was its ally in two World Wars

By Vyacheslav Katamidze

The United States of America and Russia have been involved in many of the world’s major events that have taken place on our planet. And, most importantly, it was the cooperation between the USA and the USSR and their allied relations during the Second World War that served for the benefit of all mankind.

The USSR Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko once referred to Soviet-American relations as a «swing”. Of course, he meant that at different times they were sometimes friendly, sometimes extremely complicated.

The US Declaration of Independence

If we look back, Russia undoubtedly deserves the gratitude and respect of the American nation for coming to its aid three times during the hardest periods of its history.

On 4 July 1776 the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, adopted the Declaration of Independence of the North American Colonies from Great Britain. On 2 August the document was signed by representatives of all the thirteen British colonies. A new state appeared on the world map – the United States of America.

The British Empire’s reaction was as expected: it began to prepare for the suppression of the colony’s rebellion. King George III appealed to Empress Catherine II of Russia with a request to provide him with the Russian fleet and 20,000 soldiers to fight the North American rebels, but was refused, though formally the Russian Empire was Great Britain’s ally. Catherine II was probably displeased that the British were blocking the sea routes from Europe to America, capturing or even sinking merchant ships, including Russian ones. The Empress even issued a decree on the protection of the Russian merchant marine from piracy.

Catherine II was a wise woman, and besides, she had intelligent and highly educated advisers who had extensive experience in international political and diplomatic activities. On studying King George III’s request, they worked out the following document for the Empress, which has come down to us in an abbreviated and modern form:

“You should fight for someone else’s interests only when they fully agree with your own. In this case the interests of the Russian Empire and the British Empire are not only different, but even opposite. The British want to regain their power over the former colony; we want an independent America with which we can be friends and trade without interference.

“The British Empire is large, but the metropolis itself is small and has difficulty governing the colonies. But the world is developing, and in time the colonies will become stronger than the metropolis, and it will inevitably lose them. The commonwealth of states had already declared its independence, and even if Britain deprives them of independence again, these colonies will unavoidably regain it. If Russia helps the British now, it will forever lose the opportunity to establish good relations with America.

“In addition, we would have to fight for the interests of a foreign power on the other side of the globe, where there is also a risk of military clashes with the troops of Spain and France, which have great support in the countries south of the rebellious states. If we ever strengthen our presence in America, it should be done because of our common interests with the independent states, and not with Britain.”

In the 1780s Catherine II’s diplomacy ensured that the young state, which had entered into an open struggle against the powerful British Empire, enjoyed the neutrality of other great powers and freedom from the naval blockade by the British, their allies and vassals.

Thus, the Russian Empire (along with France, which was playing its game against the British) played a significant role in lifting the trade blockade and helped provide the American rebels with everything necessary to defeat the British Empire.

In 1805, paying homage to Russians, Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence of the United States, commissioned for his Monticello estate in Virginia a marble bust of Catherine II’s grandson, the then Russian Emperor Alexander I, whom Jefferson, the third US President, regarded as the best politician of the era.

As the Patriotic War of 1812 drew to a close and the final defeat of Napoleon’s army was near, the British, believing that the whole of Europe was focused on these events, invaded the United States from Canada. Having broken down the resistance of American volunteers, the British seized Washington, burned down the White House and Congress, along with all the documents related to the Declaration of Independence. It seemed that the rebellious colonies had been subdued. However, Russia provided diplomatic and moral support to the Americans again.

The failure of the overseas adventure made the British finally accept the loss of the North American colonies and focus on developing trade relations with the young American state. Already in 1817, the United States and Britain managed to agree on the demilitarisation of the Great Lakes region.

After Napoleon’s defeat the Russian Empire became Britain’s rival, and all its actions, including the support of America, increasingly made it the British Empire’s enemy.

There is no doubt that the loss of the former colony did not reduce the commercial interests of the British in it: Britain quickly came out on top in trade with the United States. But Russia’s trade relations with the new state were developing as well.

The first seeds of cooperation were sown, though not by the two countries’ leaders, politicians or diplomats, but by the people who today are called explorers, entrepreneurs and tireless travellers, discoverers of new lands and seekers of new trade opportunities. And in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries they were called colonists and merchants looking for places where they could buy or sell something profitably.

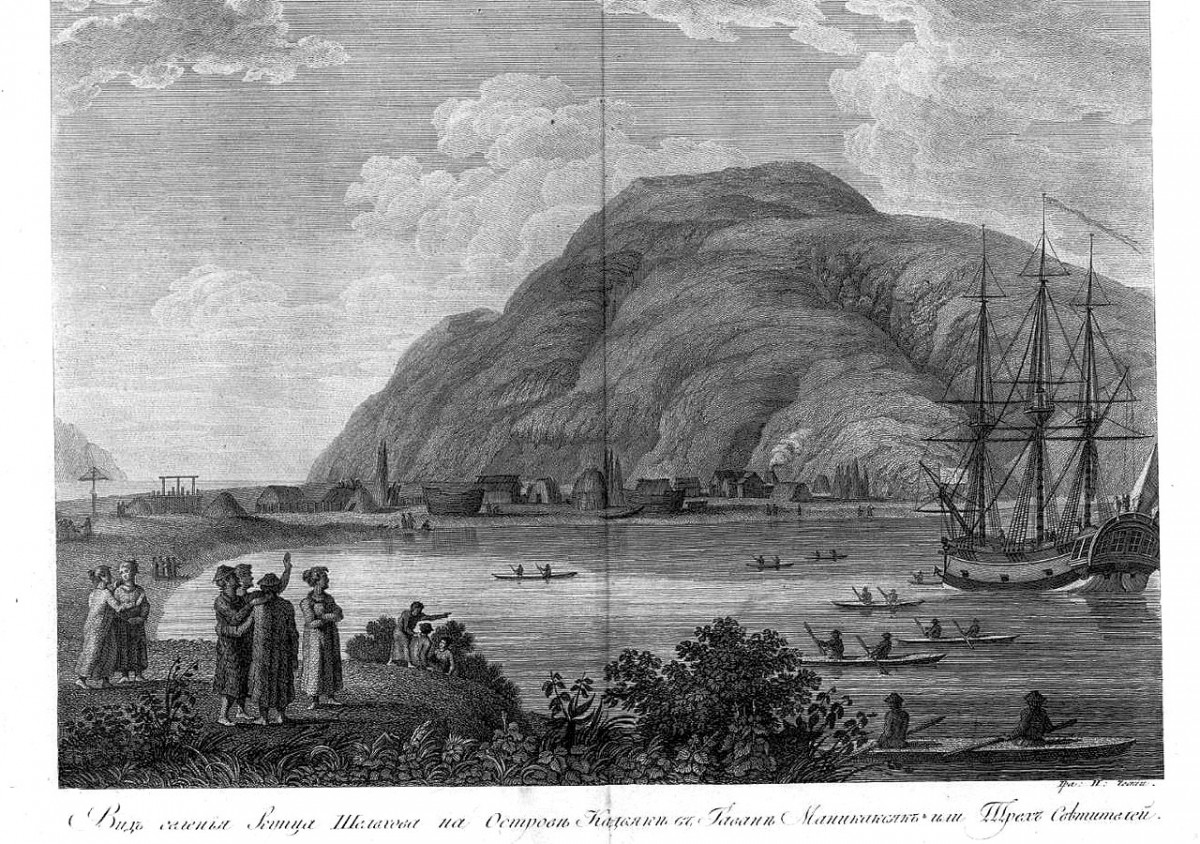

Russian America

Russian exploration of North America began with the birth of the so-called «Russian America», that is, colonies and trade missions in different areas of North America. It is believed that the first Europeans to see the shores of Alaska were members of Semyon Dezhnev’s expedition in 1648 that sailed through the Bering Strait «from the Cold Sea to the Warm Sea» (i.e. from the Arctic Ocean to the Bering Sea).

On 21 August 1732, during the expedition of A. F. Shestakov and D. I. Pavlutsky in 1729-1735, the Russian ship St Gabriel arrived in Alaska. A few years later Russian merchants, industrialists, and missionaries started exploring the Aleutian Islands.

The first Russian settlements were founded in North America as a result of the expedition of 1783-1786, led by the Russian explorer, navigator, industrialist and merchant Gregory Shelikhov. It was Shelikhov and his son-in-law Nikolai Rezanov who founded the North-Eastern Company in 1783, which was transformed into the famous Russian-American company in 1799.

By the way, Rezanov, a Russian diplomat, traveller and entrepreneur, became the first official Russian Ambassador to Japan and one of the organisers of the first Russian circumnavigation of the globe (1803-1806), commanded by Ivan Kruzenshtern and Yuri Lisyansky.

Russian America’s economy was chiefly based on sea fur industry, which mainly relied on hunting sea otters and sea lions. The fur of these animals was exchanged in China for tea and silk, which were then sold in Europe.

The first governor of the Russian settlements in North America was the trader Alexander Andreyevich Baranov, who in 1799, with the permission of the elders of the native Tlingit people, founded Fort Archangel Michael. In 1808 Novo-Arkhangelsk (now Sitka) became the chief city of Russian America.

One of the regions where private Russian companies developed successfully was California, where the Russians founded the settlement of Fort Ross in 1812.

We should also note the considerable contribution of Orthodox missionaries to the development of Russian America. Thus, in September 1794 an Orthodox mission from the Valaam and Konevets Monasteries and St Alexander Nevsky Lavra, headed by Archimandrite Joasaph, arrived on Kodiak Island. Five years later he became Bishop of Kodiak.

The development of Russian America was perceived in the western states in different ways. Local farmers and merchants believed that Russian settlements had a wholesome effect on the native American tribes and Spanish settlers throughout the area, creating an atmosphere of general benevolence and good neighbourliness. But in neighbouring states, not least in local political circles, hostility towards Russian settlers and especially towards the clergy was growing all the time. California was a fertile land, and many wealthy Americans were thinking about how to get rid of the enterprising Russians and take over their settlements.

However, in the ruling circles of the United States, politicians and economists were of a different mindset: they saw considerable benefit in developing relations with Russia – a huge country rich in natural resources, and in the future a wide market for the export of goods and services.

Establishment of Diplomatic Relations

Attempts to establish diplomatic and economic relations between the two countries were made as early as the late 1790s. The first official meeting of Russian and American diplomats was organised in London: these were the US Minister to Great Britain Rufus King and the Russian Ambassador S. R. Vorontsov, accredited to St James’ Palace (by tradition, all ambassadors present their credentials here and are listed as ambassadors at this palace, built by King Henry VIII,).

They discussed the conclusion of a trade agreement between Russia and the United States, as well as the appointment of an American minister to St Petersburg. In 1799 Emperor Paul I expressed his opinion on this matter: «We will readily agree to the establishment of mutual missions, since the American Government has earned all respect from our side by its behaviour in the present circumstances <…> and therefore, once a minister is appointed by the states, then we will proceed to that.»

In April 1803 Levett Harris was appointed the American consul at St Petersburg. Both countries were satisfied with this start of consular relations, but the British, apparently, did their best to slow down the development of diplomatic contacts between Russia and the United States, which, as before, were carried out through the two countries’ diplomatic representatives in London.

The Americans were not satisfied with this situation, so in June 1806 the question of appointing a minister to St Petersburg was raised in Washington. Realising the wisdom of rejecting any British mediation, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs agreed with the American proposal.

In 1807 the first steps were taken to establish diplomatic relations, which were formally consolidated two years later, when an exchange of ambassadors took place. Andrei Dashkov was appointed the first Russian ambassador to the United States, and the first US ambassador to Russia was John Quincy Adams – son of the second US President John Adams and the future sixth US President. His appointment was proposed by President James Madison and was approved by the Senate in July 1809.

On 24 October (5 November) 1809 Adams arrived in Kronstadt. He arrived in Moscow ten days later and presented his credentials as ambassador to Emperor Alexander I, which marked the official establishment of diplomatic relations between the Russian Empire and the United States.

After the ceremony Adams had a long private conversation with the Emperor, during which the minister expressed his firm intention to promote the expansion of trade ties between Russia and the US.

Of course, the main goal of the American mission was the all-round development of friendly relations with Russia in order to create maximum favourable conditions for trade between the two countries. But American politicians of Adams’ calibre looked far ahead: they realised that a power like Russia could eventually prove useful to the United States. And they were not mistaken: Russia would back the Government of Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War and would be their ally in two World Wars.

Adams had good personal relations with Emperor Alexander I. In 1810-1811 they met quite often and talked for a long time while walking in the palace park. Of course, an important factor in their communication was the Emperor’s mastery of English (he also spoke French and German). It seems that during these walks they probably discussed the possibilities of developing bilateral relations.

On 13 February 1811 the then-US Secretary of State Robert Smith sent Adams an instruction containing «The Basic Principles of the Treaty between the United States and the Emperor of All Russia.» Its first and main point was the «proclamation of eternal peace, friendship and good understanding» between the US and Russia.

In his diaries Adams left a detailed description of his service in St Petersburg, making a full picture of the life of high society and the Russian elite. Over four and a half years he became friends with the Naryshkins, Chancellor Rumyantsev, Princess Anna Beloselskaya-Belozerskaya and Prince Alexander Kurakin, as well as Minister of Finance Dmitry Guryev and other influential figures. Meanwhile, the salary of the American ambassador was not enough to maintain an appropriate standard of living, so Adams did not invite anybody to his place, but he often attended balls and social events.

All in all, Adams’ mission in Russia was considered very successful: he managed to establish close contacts between Russia and the United States. In addition, he acquired a number of scientific works in St Petersburg, which he donated to libraries in the United States. He is also known for being one of those thoughtful and broad-minded American diplomats who sought to learn as much as possible about what Russian people thought about America and its development, as well as what they thought about Russia in Europe. For this purpose he used both contacts with American ministers to European capitals and his Russian acquaintances.

It was not only about putting out feelers to American diplomats in Europe regarding Russia’s foreign policy aspirations, but also about probing the sentiments of courtiers and aristocrats in both Moscow and St Petersburg regarding the development of relations with America. In both cities the elite showed considerable interest in the all-round development of relations with the US.

The American journalist Edward Miller, who travelled through Europe all the way to Moscow, wrote: «It seems that Russia is tired of endless wars in Europe, from the constant lies coming out of the lips of European politicians, of the machinations of European financiers, and would be happy to be friends with people who are inclined to an open and honest agreement, transparent and unambiguous relations.»

This somewhat naive passage was probably a sincere expression of the sentiments of many Americans of the early nineteenth century.

In 1817, by decree of President James Monroe, Adams was appointed US Secretary of State and held this post for eight years.

The Monroe Doctrine and Its Consequences

The 1820s were important years for both the USA and Russia. At the beginning of this period John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State in the administration of President Monroe, put forward the idea of declaring the American continent a zone closed to the intervention of European powers. The reason for this was the Holy Alliance’s plans discussed at the Verona Congress in late 1822 to restore Spanish rule over the Latin American colonies that had declared their independence. The Congress participants – Russia, Prussia and Austria – authorised France to speak out on behalf of all three countries against the Spanish Revolution and attempts to extend intervention to the former Spanish possessions.

Britain opposed it, and its objections were understandable: some of Spain’s former colonies now belonged to it or were under its control, and it feared rivalry with France in Latin American markets. The UK Foreign Minister George Canning immediately turned to the USA with a proposal to coordinate joint opposition to the Holy Alliance’s intentions. In light of the events of the Anglo-American War of 1812-1815, John Quincy Adams deemed it appropriate to make a statement on behalf of the US.

On 2 December 1823 in a message from US President James Monroe to Congress a declaration was proclaimed that went down in history as the Monroe Doctrine. It put forward the principle of dividing the world into European and American systems of Government, proclaimed the concept of US non-interference in the internal affairs of European countries and, conversely, non-interference by European powers in the internal affairs of the countries of the Western Hemisphere. The United States also warned European powers that any attempt by them to interfere in the affairs of their former colonies in America would be regarded as a violation of the US vital interests.

The administration of President Monroe had no doubt that Russia would side with America. The US President’s message to Congress read: «At the proposal of the Russian Imperial Government, made through the minister of the Emperor residing here, a full power and instructions have been transmitted to the minister of the United States at St Petersburg to arrange by amicable negotiation the respective rights and interests of the two nations on the northwest coast of this continent.

“In the discussions to which this interest has given rise and in the arrangements by which they may terminate the occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.»

And further: «With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintain it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.»

In fact, when it comes to Russia, it was not only a warning to the European powers, but also a confirmation of the decision that Russian settlements on American soil would no longer exist.

As for America’s non-interference in Russia’s affairs, the opposite took place in 1825, even though it was not sanctioned by the US administration.

This happened in Russia in the 1820s. From 1820 till 1830 the functions of the US ambassador to Russia were performed by Henry Middleton. There is every reason to presume that this politician, slave-owner and planter, as an American diplomat acted in Russia not only in the interests of his Government, but also of the UK Establishment. The US Secretary of State trusted him completely, and this gave him full freedom of action.

Middleton spent his early years in Britain and at the age of twenty-four married the daughter of an English officer associated with British intelligence. In Russia the American diplomat paid special attention to studying not only Russia’s politics, but also its army, finances, and the attitudes of the powers that be. His wife made important connections at the court and became a friend of Elizabeth – daughter of the famous politician and philosopher Speransky, whose late wife was English. Elizabeth was brought up by her English grandmother who lived in Russia. In her younger years this woman used to serve as a governess in noble families close to the Government, and it was suspected that what she saw and heard in these families became known to UK agents.

In turn, Speransky was on friendly terms with Count Nesselrode, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs. It turned out that Middleton had access to very serious sources of information that came from him to both Britain and America.

In December 1825 an uprising with the aim of a coup took place in St Petersburg. It was undoubtedly in the interests of European countries such as Austria, the UK and France, as Russia would have been seriously weakened by internal strife.

The UK was most interested in the success of a coup. The establishment of constitutional power in Russia would undoubtedly have given it the opportunity to use contacts with its trade and financial capital for economic ties with Russia, to begin extensive exports of raw materials and the slow enslavement of the country.

After James Monroe’s presidential term had expired in March 1825, John Quincy Adams was elected US President by the House of Representatives. The new President carried on the policies of developing relations with Russia.

Sale of Alaska

In April 1824 the Russo-American Treaty on Friendly Relations, Trade, Navigation and Fishing was signed, which fixed the southern boundary of the Russian Empire’s possessions in Alaska. A year later the Anglo-Russian Treaty was signed, establishing a demarcation line separating Britain’s possessions: it passed sixteen kilometres from the ocean line. Before that, the Rocky Mountains had been considered the unofficial boundary. Meanwhile, Russia on its part had never tried to cross the Rocky Mountains, though for almost half a century this land had been absolutely uninhabited. As we can see, the Russians created the basis of the infrastructure in this part of North America.

It is clear from all that has been said that the Russian Empire’s plans to acquire trade and economic footholds in North America were being implemented, and the colonization of several areas of Alaska was progressing successfully.

Why then did the Russian Empire decide to leave these territories, agreeing to sell them for a very modest sum of $7.2 million? We believe that one of the reasons was the desire of industrialists and tenants of lands in the territories adjacent to the lands of Russian companies to take possession of these lands in the event that the Russians left.

In historians’ view, the second reason was the betrayal and avarice of the then Russian Ambassador to the United States Edouard de Stöckl. Of an Austrian descent, he assumed this post after the death of Ambassador Alexander Bodisko, whose assistant he had been.

Stöckl constantly sent alarmist messages to St Petersburg about a threat of war round the Russian territories and about the growing dissatisfaction of American politicians with the «presence of Russians on American soil”. They believed him. As a result, he successfully sold the territories near San Francisco, and then Alaska. In 1867 Stöckl signed the agreement to sell Alaska, for which he received special thanks from the Russian Emperor, the Order of the White Eagle, a one-time remuneration of 25,000 roubles and a lifetime pension of 6,000 roubles annually.

It should also be noted that the Russian Empire’s decision to sell Alaska and other lands in North America was largely dictated by the promises of American politicians to be friends with Russia, trade widely with it, support it in the political arena and always be on Russia’s side in military conflicts in exchange for leaving American soil.

Friendly Neutrality

During the Crimean War of 1853–1856 the United States adopted a position of friendly neutrality towards Russia, which was expressed in the support by American public opinion and the participation of volunteers on the side of the Russian Army. US officials pointedly ignored the celebrations organised by the British and French in American cities on the occasion of the fall of Sevastopol. A crowd even trashed some banquet halls. Attempts by the British to recruit Americans into their army led to a big diplomatic scandal.

During the Crimean War about fifty American doctors came to Russia to work at the hospitals of besieged Sevastopol.

All of them had recommendations from reputable individuals and were officially employed by the Russian Government on a salary five times higher than the usual salary of a Russian doctor and twice the average income of a doctor in America. Though they all already had considerable medical experience, at that time it was believed that the only way to gain experience in surgery was to engage in field surgery during war.

Enthusiasts also set off on a long and difficult voyage, driven by the desire to help the sick and wounded. The physician A. Ph. Moullet from Nashville wrote that he went to war, leaving his wife and two children at home, certainly not for financial reasons (since almost ten years of work experience had provided him with a good practice at home), but out of a desire to “serve a useful service, maintain the prestige of his profession and show that there were good surgeons in the United States.” Most of the American physicians arrived in besieged Sevastopol, as well as in the hospitals of Kerch and Simferopol.

The hospital in Sevastopol was organised in the building of the Noble Assembly. This is how E. M. Bakunina (great-niece of Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov), one of the first nurses, described in her reminiscences the hospital where American surgeons worked: «The beautiful building, where people used to make merry, opened its rich mahogany and bronze doors to bring in bloodstained stretchers. A large white marble hall with pink marble pilasters across two floors, with windows only at the top. Parquet floors. And now there are up to 100 beds with grey blankets and green tables in this former dance hall. Everything is clean and tidy. <…> On one side there is a large room – now an operating theatre, formerly a billiard room, and behind it there are two more rooms <…> On the floor there are mattresses without beds in several rows, a few tables with paper, and on one there are lotions and piles of lint, bandages, compresses, and sliced stearin candles. There is a big samovar in one corner, which boils and is supposed to be boiling all night long.»

- W. Reed, a surgeon from Pennsylvania, was proud of his work being approved by the «miracle doctor» Nikolai Pirogov, the founder of the Russian school of field surgery. Another American physician, Charles Park, commenting on rumours about the departure of the American ambassador from London and the UK ambassador from Washington, wrote in his diary in late 1855: «America and Russia can flog the world. If this is going to happen, let’s say goodbye to British rule and monarchy – its days are numbered.»

After the end of the Crimean War the American volunteer doctors returned to the United States. Russia appreciated their feat: all were awarded silver medals «For the Defence of Sevastopol» and bronze medals «In Memory of the Crimean War of 1853-1856”. Some received Russian orders. Doctor P. Harris was awarded the Order of St Stanislaus. The same award was conferred on J. Holt, I. A. Lis, W. R. Trol, and the surgeon Ch. Henry received the Order of St Anna (the third degree). The physician Whitehead, who received Russian awards for his labours, emphasised in one of his letters that they would serve as a proud reminder that he «had been honoured to help the officers and soldiers who had covered the Russian arms with glory and won immortality to Sevastopol.»

Russian physicians commissioned a commemorative silver medal, commemorating the selfless work of their colleagues. The obverse of this medal is engraved with a cross with equilateral arms, a medical badge and the words «Sevastopol. Everything that could be done has been done.» On the reverse is the inscription: «To American colleagues from grateful Russian doctors in memory of their joint labours and hardships.» The medals were presented by Pirogov personally.

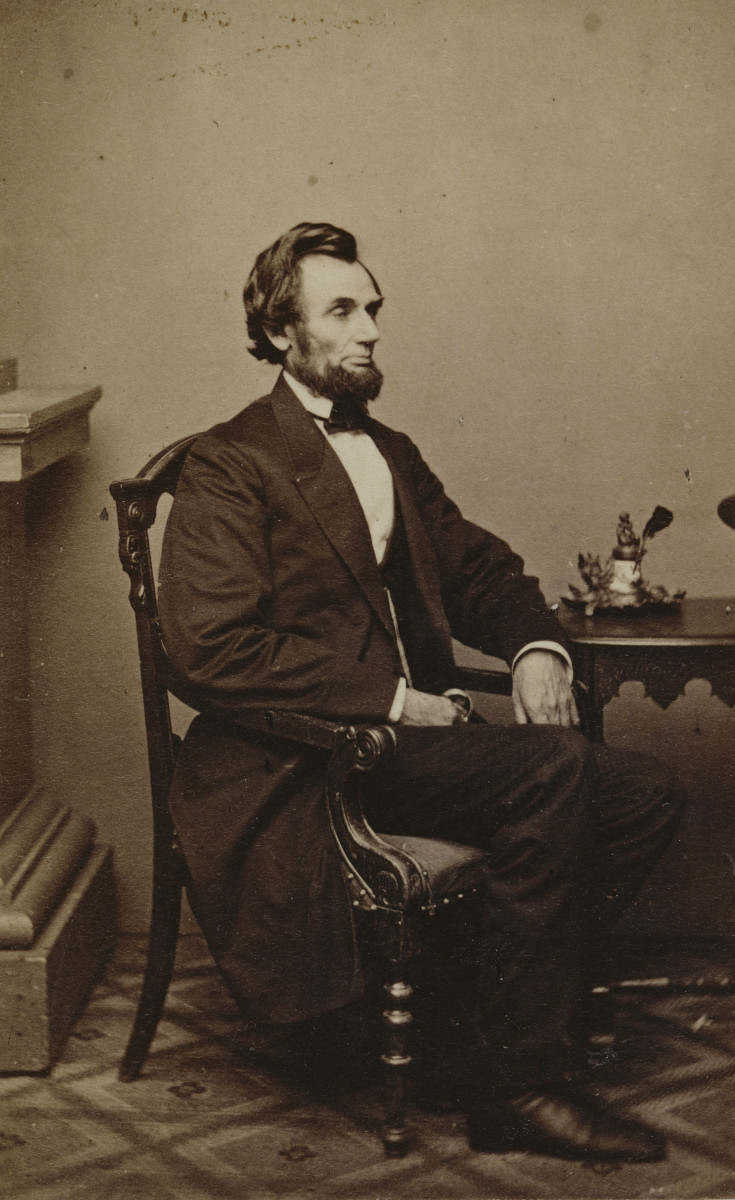

The American Civil War

In April 1861, just five years after the end of the Crimean War, the Civil War broke out in the United States of America, which lasted four years.

Following the Declaration of Independence in the USA, the slave system and capitalist production coexisted side by side, but the moment came when the two social systems inevitably collided.

In 1860 the United States split: the opposing sides in the outbreak of the Civil War were the US federal Government, backed by twenty-four states in the North (twenty non-slave owning and four slave-owning), or the Federal Union, and the Confederacy of eleven slave-owning states in the South.

The balance of power between the North and South was clearly not in favour of the latter. There were twenty-four states in the North with a population of 22 million. The South had eleven states with a population of 9 million. The Confederacy was going to fight for the preservation of the institution of slavery. Meanwhile, there were about 4 million slaves among these nine million. But most importantly, the North had a highly developed industry and a more extensive network of railways and shipping channels. In the event of a prolonged war the Confederacy had no chance of winning.

But, starting the war, the Confederacy still hoped to win. However, their expectations were not based on the possibility of winning on their own, but on the inevitability of intervention by the UK and France.

On 31 October 1861 Britain signed a treaty with France and Spain to intervene in Mexico. In December Spanish troops landed in Vera Cruz. In January 1862 the UK and French troops joined them.

Shortly after the start of the intervention of the three powers in Mexico, initiated by UK Prime Minister Henry Palmerston, the threat of British intervention loomed over the Union, which was suffering severe defeats at the front. The blockade of the Confederacy declared by the Union, which cut off the export of American cotton, caused great irritation in Europe.

On 26 March 1861 Lord Lyons stated at a meeting with US Secretary of State William Seward: «If the United States determined to stop by force so important a commerce as that of Great Britain with the cotton-growing States, I could not answer for what might happen.»

The UK authorities, stirring up an anti-American campaign in the press, called on their country to go to war with the former colony; new warships were being built at an accelerated pace in the English shipyards and old ones were being improved.

However, in time it became clear that the Confederacy’s hope for intervention and the magical effect of blocking cotton exports proved to be in vain. The advantage of the Union in the Civil War grew, slowly yet steadily. Trying to save the situation, Palmerston called on Foreign Secretary William Russell to recognise the Confederacy. A cabinet meeting to consider this issue was planned for late September 1862, but the British were too late with their decision: a preliminary proclamation on the emancipation of slaves was issued in the United States. As a result the issue of recognising the Confederacy was removed from the agenda of the UK Cabinet meeting.

By that time, Russia and the US had developed very good relations. The neutral and benevolent position taken by Washington during the Crimean War was highly appreciated in St Petersburg. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, and later the Chancellor of the Russian Empire, Prince Alexander Gorchakov, wrote about this: «The sympathies of the American nation towards us did not weaken throughout the war, and America rendered us, directly or indirectly, more services than could be expected from a power adhering to strict neutrality.»

While the UK and France tried to make use of the Civil War in the US, the stance of the Russian Empire remained principled and unchanged. Prince Gorchakov expressed it this way: «Russia’s policy towards the United States has been determined and will not change depending on the course of any other State. Above all we wish to preserve the American Union as an undivided nation <…> Proposals have been made to Russia to join the intervention plans. Russia will reject any such proposals.»

In order to support the Government of President Lincoln and prevent UK and French military intervention in the American Civil War, Russia sent two squadrons of its fleet to the US shores on 25 June 1863. The first squadron, under the flag of Rear Admiral Stepan Lesovsky, had six ships with a crew of 3,000. The second squadron, commanded by Rear Admiral Andrei Popov, consisted of six ships and 1,200 officers and sailors.

The appearance of the Russian fleet off the coast of North America caused euphoria in the Union and was interpreted as a symbol of Russian-American friendship.

The Russian naval mission was in the United States for nine months. Throughout this time, the squadrons did not take part in combat operations, but their very presence off the west and east coasts of the US prevented the UK and French intervention.

In late July 1864, when St Petersburg considered the mission’s tasks completed, the commanders of both squadrons were ordered to leave American waters and sail back home.

The political results of the mission were highly appreciated in both capitals.

By the way, Switzerland was the only European country apart from Russia to support the Union.

The American Civil War ended with the surrender of the Confederacy on 9 April 1865. Five days later – on 14 April 1865 – Abraham Lincoln was fatally wounded in Washington DC during a performance at Ford’s Theatre.

After the President’s death, the so–called «conciliators» came to power – politicians who sought compromise with the southern states on all issues. As a result, good relations with Russia ceased to seem important to the Establishment. Lincoln’s enemies were convincing Americans that everything he had done was a pile of errors, including friendship with Russia…

The famous American diplomat James Keats wrote in 1868: «Russians are clever, hardworking and enterprising. It would be unwise to give them the opportunity to have colonies or even concessions on our land, as they will then be able to strengthen not only their presence on American soil, but with time they will also gain leverage over our politicians. We need to get rid of their presence in America as soon as possible. Of course, we can be friends with them in words, but in fact our policy towards Russia, its Emperor and politicians should be based on practical benefits rather than truly friendly relations full of trust or common interests (my italics – V. K.).”

This concept was gradually becoming the basis of US policy towards Russia. American politicians and diplomats continued to assure the Russian ambassadors of their faithfulness to the Russian Empire, but different sentiments prevailed within the American elite.

And yet, for the most part, American people sincerely treasured Russia’s friendship and support during the tough times of the American Civil War.

Two World Wars of the Twentieth Century

The twentieth century was a long period when the nature of relations between Russia and the United States changed especially frequently. It was not at the whim of their leaders, but mainly because serious events related to world politics and wars had a huge impact on Russia and other European countries. True, wars had often taken place on our planet before, but in the twentieth century humanity was shaken by two World Wars. Both Russia and the United States participated in these wars, as well as in many regional conflicts. During these events their priorities, interests and, accordingly, their positions in the global geographical and political space changed.

Russia was one of the countries whose situation changed depending on its own revolutionary transformations and on the fate of the rest of the world.

In the first decades of the twentieth century the radicalisation of a significant part of the Russian population made it clear to politicians in many European countries that, in essence, it had only embarked on the path of serious socio-political transformations and, consequently, European countries could take advantage of this process to gain considerable financial benefits. Western capital and the international industrial and financial circles of Germany, Austria, the UK and the USA were behind many socio-political events in Russia at the beginning of the century.

Caught in the fetters of commercial and usurious capital, for some time Russia obediently followed the path chosen for it by other countries’ elites; however, the end result of this process was not subordination to them, but the opposite: the Revolution of 1917. The fact that it took place during the First World War aggravated the situation.

By the time Bolshevik rule was established in Russia, the share of American capital in the country’s economy was small: US investments accounted for approximately five per cent of all foreign investments. Most of the prominent figures of social democracy, and first of all the Bolsheviks, believed that following the Russian proletarian revolution a whole series of similar revolutions would break out in Europe. Meanwhile, the First World War was only a new stage in the divisions of the world, and Russia’s opponents in this war were such imperialist predators as Germany and Austria-Hungary.

By agreeing to the shameful Peace of Brest-Litovsk, the Bolshevik Government counted solely on the respite in the war, which would enable it to consolidate its power.

At first the Soviet Government believed that with the help of connections that a number of Bolshevik figures had in the USA, and using the vast resources of their own country, they would be able to attract American capital to Soviet Russia. Besides, there were voices claiming that broad cooperation between the two countries would be established in a short span of time.

In 1918 through a representative of the American Red Cross the Bolshevik leaders conveyed to the US business community an offer of cooperation involving the granting of a number of concessions to American businessmen in Soviet Russia. No one in the United States paid any attention to these proposals; instead, the Americans took active part in the Allied intervention in Russia alongside Entente powers.

Then, using its business and family ties, the Soviet Government set up a Soviet representative office in New York, which was engaged in recruiting American businessmen to open companies in Russia. It was headed by Ludwig Martens, the son of a major German industrialist and Lenin’s associate from the Marxist circle.

The only achievement of this representative office, for the maintenance of which huge sums were spent in two years, was that several thousand socialist workers went to work in Soviet Russia. Martens and some of his colleagues were soon expelled from the United States because they tried to hold mass events that called for recognition of Soviet Russia.

In an effort to halt US participation in the intervention, People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin appealed to the US President W. Wilson in which he called for «an end to actions that harmed Russian lives and the Russian people» in exchange for providing extensive business opportunities and various concessions to American business and the business circles of the UK and France. This call was not answered straight away. Only after it became obvious that the Bolsheviks had consolidated their power did the Western European countries, and then the USA, one by one begin to recognise the Soviet Government.

It should be noted that the businessmen or firms in the USA that already had commercial ties with Russia demanded that normal diplomatic and trade relations be restored with it. The issue of recognition of the Soviet Union was constantly raised by American workers, and it was actively discussed in the American press.

In July 1920 the American authorities lifted the embargo on trade with Russia. Soon US industrialists began to receive concessions in Soviet Russia. The first of them was Armand Hammer, who obtained a concession to mine asbestos near Alapaevsk in November 1921.

The Hammer brothers, who were well aware of the numerous priceless artistic treasures in Russia, acted as intermediaries between the Soviet Government and American art dealers and collectors during the sale of the USSR museum treasures. After leaving the Soviet Union in the early 1930s, they sold the treasures of the Romanov Dynasty, the masterpieces of the Hermitage Museum, and jewellery made by Carl Faberge. By Lenin’s order, Hammer was given dozens of paintings from the Hermitage Museum to be sold in the USA, including Raphael’s unique painting, St George and the Dragon.

In the 1960s Hammer was reckoned as a «great friend of the Soviet Union» and a personal friend of General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Leonid Brezhnev. American historians claimed that Hammer was a link between some Soviet leaders and seven US Presidents.

Hammer invested a large sum in the building of the World Trade Centre in Moscow, and it was there that the author of this article interviewed Armand Hammer briefly in 1987. When asked if he liked the centre, which was nicknamed the «Hammer centre”, he replied with a smile: «Everything I do always turns out great!»

Hammer built the TogliattiAzot ammonia production complex in Russia and the Tolyatti–Odessa ammonia pipeline. He also financed the building of Odessa and Ventspils portside factories for the production of liquid ammonia fertilisers.

From 1919 on, the Ford factories cooperated extensively with Soviet Russia: they supplied cars and tractors. In 1923-1924 alone Ford Motors supplied ninety-one passenger cars, 346 lorries, and 3,510 tractors to the USSR. In the early 1920s the USSR was a market for American goods, as can be seen from the following figures: in 1924 exports from the USSR to the US amounted to only 797,000 roubles, while American supplies to the Soviet Union amounted to 18.7 million roubles.

Of considerable importance for the increase of American imports to Soviet Russia was the fact that, after visiting it in 1923, a group of the US Congress members came to the conclusion that the position of the Soviet Government was strong, and the USSR was «a country of tremendous opportunities and a huge market.» And if America did not come to an agreement with the Soviet Government straight away, others would take its place.

The Soviet-American diplomatic relations were established in 1933 during the first year of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency. To a certain extent, this was a forced measure: it was during the Great Depression – the most severe economic crisis in the USA. Relations between the two countries were developing rapidly.

In late July 1937 for the first time in the history of Soviet-American relations there was the Friendship Visit of a detachment of ships of the US Navy to Vladivostok: the cruiser Augusta and four destroyers stood in the port of Vladivostok for several days. The symbolic significance of this event cannot be overestimated.

But by the end of the 1930s the US attitude towards the Soviet State began to change, in particular, owing to the Soviet-Finnish Winter War of 1939-1940. The USA froze Soviet assets and imposed a «moral embargo» on fuel supplies to the USSR.

It was only after Germany’s active military preparations against the USSR and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour that the Western Allies began to realise the true picture of the aggressive actions of Nazi Germany and militaristic Japan. Subsequent events – the end of the Winter War, the occupation of France, and the Blitz– convinced the USA to change its stance and establish allied relations with the Soviet Union without delay.

The first foreign diplomat to inform the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the USSR about Germany’s impending and imminent aggression against the USSR was the US Ambassador to the USSR Laurence Steyngardt. It happened on 15 April 1941. Speaking with First Deputy People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs Andrei Vyshinsky in May, he raised the issue of the need for a Soviet-American alliance against the expansionist policies of the Nazis. «It would be very good if the United States stood against Germany on one side and the USSR on the other,» he said during the talk with Vyshinsky.

But the «moment of truth» in Soviet-American relations was the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War. According to Gallup polls conducted from 26 June till 1 July 1941, seventy-two per cent of Americans supported the Soviet people.

On 26 June Deputy Secretary of State Wallace expressed the official attitude of the United States towards the German invasion of the USSR: «The American Government considers the USSR to be a victim of unprovoked and unjustified aggression. The US Government also believes that the repulse of this aggression, which is being given now by the Soviet people and army, is not only dictated, in the words of Mr Molotov, by the struggle for the honour and freedom of the USSR, but also agrees with the historical interests of the USA.»

Lend-lease

It was the largest US programme in the history of the twentieth century to help the Allies during the Second World War. It was carried out on the basis of a US State Act, which became law after it was signed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

On 27 July 1941 President Roosevelt instructed his personal representative Harry Hopkins to meet with representatives of the Soviet Government. On 28 July Hopkins travelled to Moscow via Arkhangelsk. On 30 July he met with Joseph Stalin.

Hopkins was authorised by the President to discuss and resolve all issues related to the Soviet Union’s receipt of American loans for the purchase or lease of weapons. Hopkins received both urgent and long-term requests from the Soviet leadership and sent them to the USA. Considering the first category, Stalin requested 20,000 anti-aircraft guns, heavy machine guns and over a million rifles.

As for the second category, Stalin requested high-octane aviation petrol and aluminium for aircraft production. He said that 200 P-40 fighters had already been delivered to the USSR (140 from the UK and sixty from the USA), and this was a serious help for the Soviet Air Force in the first months of the war.

Hopkins, for his part, expressed to Stalin the gratitude of the people of the USA for the steadfast and courageous resistance to aggression by the Red Army, and stressed that the American President was determined to do everything in his power to support the Soviet Union in its valiant struggle against the German invaders.

On 1 August 1941 Hopkins conveyed to the US President through Ambassador Steinhardt his assessment of the situation on the Soviet-German front. In his opinion, the front was reliable, the morale of the Russian soldiers was high, the army was fighting bravely and believed in its victory. This message was extremely important, as the Allies, not least the UK, doubted the strength of the Soviet front and, consequently, the expediency of massive supplies of weapons and other shipments to the USSR. Now just the opposite was happening: on 2 August the Soviet ambassador to the USA was announced that the USSR had been granted a variety of licences. The document submitted to him stated: «In order to facilitate the expansion of economic aid to the Soviet Union the State Department also issues unlimited licences allowing the export to the USSR of a wide variety of products and materials necessary to strengthen the defence of this country in accordance with the principles applicable to the supply of such items and materials that are needed for the same goals for other countries resisting aggression.»

Not all the functionaries in the United States agreed with this document. There were indications that some employees of the US Department of War artificially delayed supplies, but Roosevelt quickly corrected this situation: he demanded daily reports on the execution of Soviet applications. In fact, it was the fulfilment of the will of the American people: on 27 October a rally in support of the Red Army and the Soviet people was held in New York, which attracted 25,000 American citizens. The former US Ambassador to the USSR Joseph Edward Davis spoke at the rally. In early November, in the wake of the Soviet Union’s support, an interest-free American loan of $1 billion was approved (with payments for a period of ten years starting five years after the end of the war).

In accordance with international agreements, in 1941-1945 the United States supplied lend-lease arms, military equipment, ammunition, explosives, medical equipment, various types of raw materials (including oil products), industrial equipment, food and spare parts for supplied armoured and automotive vehicles to its Allies in the fight against the Axis countries. All this was transferred to the Allies for free till the end of hostilities.

The USA began to provide aid to the Allies as early as September 1940, though they themselves did not enter the war until December 1941.

Initially, most of the supplies of weapons and other military products were sent mainly to the countries of the British Commonwealth, which were already at war with Germany and Japan. But after the Nazi invasion of the USSR the United States, realising the importance of the Soviet-German front, announced that they would send weapons and other important supplies to the Red Army as well.

President Roosevelt was aware that if Nazi Germany defeated the USSR, the Allies would most likely lose the war. Therefore, aid to the Soviet Union was recognised as a priority.

On 7 November 1941 the Lend-Lease programme was officially extended to the Soviet Union.

Andrei Gromyko called Roosevelt’s letter to his assistant, US Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, published by the White House, a historic document and a new milestone in Soviet-American relations, in which the USSR was designated «a vital country for the defence of the United States”.

The end of 1941 became crucial in Soviet-American relations. The staunchness of the Soviet people roused sympathy in American society. The defence at the Battle of Moscow was described in the USA as unprecedented and heroic.

The USSR Air Force received 18,200 aircraft under lend-lease – about a third of the total number of fighters and bombers produced at Soviet factories throughout the war.

The Red Army received 7,000 American and 6,000 British tanks. It was eight per cent of the total number of tanks produced in Soviet factories. And though Soviet tanks were generally superior to American and UK models in terms of their tactical and technical qualities, but in conditions when the Soviet Union was fighting a strong and well-armed enemy, any number of combat vehicles supplied by the Allies was of great importance.

Over five years of the war the volume of shipments supplied to the USSR under lend-Lease increased to astronomical proportions. Their total tonnage was 17.5 million tons. The operation of the Lend-lease Law was repeatedly extended not only during the war, but also for the first post-war years.

In total, from 1 October 1941 till 31 May 1945 the USA supplied the Soviet Union with 427,284 lorries, 13,303 combat vehicles, 35,170 motorcycles, 2,328 ammunition vehicles, 1,911 steam locomotives, 66 diesel locomotives, 1,000 dumpcars, 120 cisterns, 35 wagons of heavy machinery, 2,670,371 tons of oil products (petrol and oil), or 57.8 per cent of aviation fuel, including almost ninety per cent of high-octane fuel, as well as 4,478,116 tons of food (tinned meat, sugar, flour, salt, etc). In 1947 the total monetary value of lend-lease supplies and services was about $11.3 billion.

Shipments for the Soviet Union were delivered via three routes: the Arctic convoys, the Persian Corridor and the Pacific route. The Arctic convoys followed the shortest, but the most dangerous route, as it passed by the German-occupied Denmark and Norway: the convoys were attacked by German submarines and Luftwaffe aircraft. During the use of Arctic convoys, 104 Allied merchant ships and eighteen warships were sunk. About 3,000 sailors died heroically defending the convoys from the Nazis.

The Pacific route was safer, but longer, while providing about half of the lend-Lease supplies.

The first shipments to the USSR via the Persian Corridor began in November 1941, but it also took too long: the sea part of the route from the United States to the coast of Iran alone would take about seventy-five days.

In response to the aid provided, the Allies received from the Soviet Union 300,000 tons of chromium ore, 32,000 tons of manganese ore, and large amounts of gold, platinum, timber, etc. In 2006 the Russian Federation, assuming responsibility for all debts of the USSR, fully paid off the United States for the aid provided under lend-lease during the Second World War.

Lend-Lease supplies were an essential and effective aid to the Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War. They allowed the Soviet economy to overcome the enormous wartime challenges. However, it is also generally known that the fate of the Second World War was mainly being decided on the Soviet-German front, where, thanks to the heroism of the Red Army, over 600 divisions of the Third Reich were crushed.

The meeting of Soviet and American soldiers on the Elbe in April 1945 became a symbol of the fighting brotherhood of the Allied Forces of the anti-Hitler coalition, united by the common objective of defeating fascism and the forces of evil in general.

In May 2025 Russia marked a significant date: the eightieth anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War. Looking back at the decades that have passed since the Second World War, we can’t help but ask ourselves this question: do we realise and do the USA citizens realise how much our two nations could have done for each other over eighty years if there had been no cold war and confrontation, but eighty years of cooperation for the development of the two great powers?